List of Iona place-names beginning with 'I'

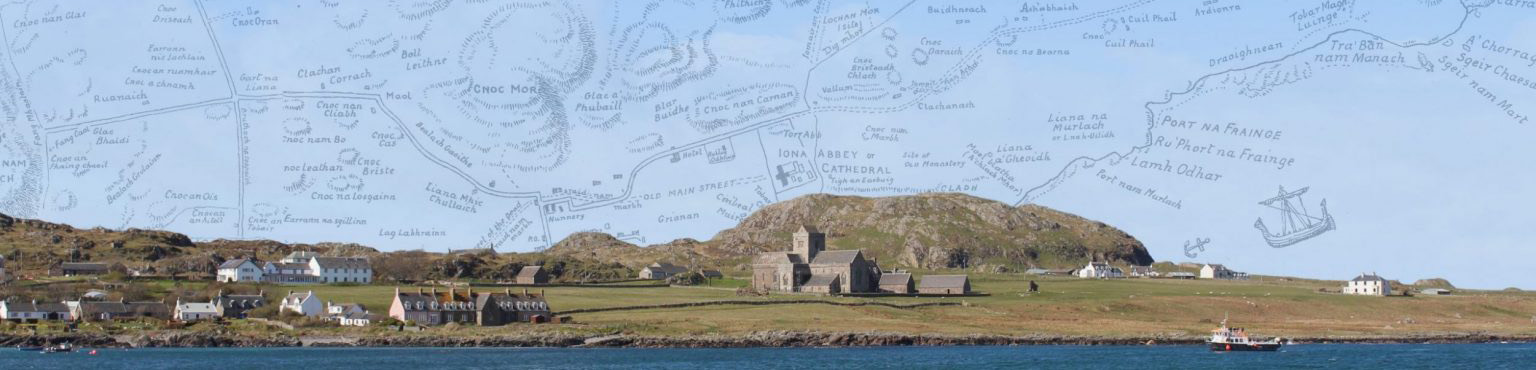

Ì | Iona

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Island

Grid reference: NM2760223745

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 20m

Description:

It is important to note that the earliest forms of this name all occur in the context of Latin records, not Gaelic. This means, if we assume that the name is a Gaelic one, that we are at one removed from the original name when we find such forms. Those earliest Latin records also represent the name in its genitive form, Iae, implying that the Latin name underlying these forms is Ia in the nominative case. This suggests that, at least in Latin contexts, the island-name was uttered as a diphthong, probably /ˈia/.

The earliest Gaelic form of the name, however, was probably a simple long vowel sound, /i/. This is suggested by Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica, where the name is written Hii, and also by the form in the Annals of Ulster (s.a. 791) where the name first appears in a Gaelic context as Hi. In AU 802 that single long vowel reappears as I Columbae Cille, this time in a Latin context, and in 986 as Í Coluim Cille, the name Í now being combined with the name of the saintly monastic founder.

None of this helps us to understand what the name Í might have meant, however. W.J. Watson explored the early forms of this name, and was influenced by the form of the name used by Adomnán in his Vita Columbae in the late seventh century. Adomnán calls Iona Ioua insula, where Ioua is an adjectival coining using the -oua suffix to create a new form of the name. This pattern of taking an island name and adding a suffix to create an adjectival form is his preferred way of referring to islands. So in VC Mull becomes Malea insula, Eigg becomes Egea insula, Tiree becomes Ethica terra or Ethica insula, and Coll becomes Coloso insula. Watson recognised this pattern, but he still treated the u of Ioua insula as if it were not merely part of an adjectival suffix but was organic to the name (Watson 1926, 87-8). He supports this by reference to another spelling of the name, Eo, found in Walafrid Strabo’s poem on the martyrdom of Blathmac in the early ninth century. It is hard to know how much weight to give this form, given that Walfrid was a Germanic monk, and was writing in Latin, and may even have been familiar with a form of the name derived from Adomnán’s Ioua. The same doubt arises from Watson’s use of the Life of St Cadroe in which the island-name is given as Euea – again a Latin source, written by a German monk in Metz in the late tenth century, and again possibly influenced by Adomnán’s Ioua. Watson’s conclusion that the u (or o) in these early forms points towards an original *Ivo or *Ivova meaning ‘yew place’ is therefore not convincing. The presence of a u in those Latin forms may simply echo Adomnán’s adjectival suffix, -oua. The complete absence of a u from all the earlier forms in the Annals of Ulster, consistently rendered Iae or Ie also casts doubt on Watson’s explanation. The sole possible exception to this is the entry s.a. 716, which refers to the change in the date of Easter ‘in Eoa ciuitate’, but it is not certain that this refers to Iona (which is not spelt that way elsewhere in AU, nor is it referred to elsewhere in AU as a civitas); the name very well refer to Mayo, in Gaelic Mag Eó, ‘plain of the yew trees’.

In spite of the authority of Adomnán, there seem to have been several centuries after his death (in AD 704) during which his spelling of the name, Ioua insula, was more or less ignored. We continue to find Latinate Ia (genitive Iae or Ie), alongside the more Gaelic-looking form Hi (even in Latin contexts). The addition of the saint’s name, to form I Cholaim Chille (AU 778 for example, along with Hi, Hij, Hii, Hy etc.) retains that form of the name which is still the modern Gaelic spelling: Í. It is not until the thirteenth century that Ioua comes back into vogue, presumably as a result of people reading Adomnán’s Vita Columbae. And it is now that we have to pay close attention to the handwriting in which the name appears in various manuscripts. Medieval scripts represent both n and u as a conjoined pair of minims (short verticle lines). Often the only way of distinguishing one from the other is by ascertaining whether the joining stroke connects the minims at the top (for n) or at the bottom (for u). Sometimes it is hard to tell the difference, and so a rendering of the name may actually be showing Ioua or Iona.

The name appears in the Verse Chronicle (1214 x 1264; see Anderson, Kings and Kingship, 60-61), in a couplet written sideways in the margin of the Melrose Chronicle: ‘The island of Iona has these men, buried in the tomb of kings, until the day of the Judge’ (Hos in pace viros tenet insula Ioua sepultos / in tumulo regum judicis usque diem). The manuscript hand of the Melrose Chronicle makes it quite clear that the spelling is Ioua, not Iona, the joining stroke being clearly at the bottom. Our island-name appears again in the form Ioua circa 1317 in Regnal List I, where Anderson says that the form is clear, though at another occurrence in the manuscript it is ‘ambiguous’ – i.e. it could be read as Ioua or Iona – but as it is Ioua at the point where it is clear, it is natural to read the ambiguous form in the same document as Ioua as well (Anderson, Kings and Kingship, 282n.). Similarly ambiguous are the spellings of the name in Regnal List K. The manuscript in a good fourteenth-century hand was read by Anderson as giving the form Yona as the supposed burial-place of various kings. But as she says, ‘the letters u and n are not always distinguishable’, and that is certainly the case where Yona or Youa is concerned. We cannot be certain that Regnal List K intends Yona as the name.[1]

We might hope to find some useful evidence in the work of John of Fordun, whose Chronica gentis Scotorum was written in the 1380s,[2] and contains several references to Iona. Fordun mentions, for example, the alleged burials of kings on Iona (IV, 26, 33, 38, 44: V, 8). In these occurrences of the name, Fordun seems to spell the name Iona, but this may be deceptive. We will return to these references in due course. When he talks of our island in more descriptive detail, he says this: ‘The island of Hy Columbkille, where there are two monasteries, one of monks and another of nuns; and there is a sanctuary there’ (Insula Hi Columbkille, ubi duo monasteria sunt, unum monachorum, aliud monialium, ibidem itaque refugium) (II, x). When he talks of Iona in detail, then, he calls it Hi Columbkille, using its Gaelic name rather than the Latinate name Ioua or Iona. He does, however, discuss the name Iona in a different context: when he is writing about St Columba he says ‘He shared a name with the prophet Jonah (Iona), for Iona in the Hebrew tongue is rendered Columba in Latin, and is pronounced Peristera in Greek (Hic cum Iona propheta sortitus est nomine. Nam quod Hebraica lingua Iona, Latina vero Columba dicitur, Graeca vero Peristera vocitatur) (III, 26). This tri-lingual play in Hebrew, Latin and Greek on the names Columba and Iona – Iona as the name of the prophet, but not of the island – is presumably taken from the Second Preface of Adomnán’s Vita Columbae.[3] Fordun does not make any connection between Iona as the Hebrew version of the Columba’s name and Iona as the name of Columba’s island. This is rather strange, given that in the surviving manuscripts of Fordun he seems to refer to the island as Iona too. Surely, we might think, since Fordun knew that Iona was the Latin word for Columba, and if he had thought that Iona was the Latin name for Columba’s island, he would have commented on the connection. But he did not.

One explanation for this might be that Fordun himself did not actually refer to the island as Iona, but referred to it as Ioua. The surviving manuscripts of Fordun’s work use the form Iona, but there may be a good reason for that. Most of the medieval manuscripts containing Fordun’s Chronica are actually copies of Walter Bower’s Scotichronicon, written in the 1440s. Bower incorporated the five books of Fordun’s work, and part of the sixth, as the first part of his Scotichronicon. In all the manuscripts of Bower’s work, which include Forduns Chronica, our island-name is written Iona, but we would expect that because that was how Bower spelt the name – as we shall see shortly. Bower, copying Fordun’s work into his own, would transcribe whatever Fordun had written – whether it was Ioua or Iona – as Iona, because that was how Bower spelt it. And of course all subsequent copies of Bower’s work would reproduce that spelling.

There are also eight manuscripts of Fordun’s Chronica which are not embedded in Bower’s Scotichronicon, but contain Fordun’s work as a stand-alone text. But all of these manuscripts post-date Bower’s work, and it is quite possible that even where these texts of Fordun spell the name as Iona they do so under the influence of Bower’s spelling on later scribes.[4] It is possible that Fordun spelt the name as Ioua, which is why he did not make the connection between the island name, Ioua, and the Hebrew name of the saint, Iona.

It is not until the 1440s that we finally encounter a clear and unambiguous occurrence of the island-name spelt with an n, as Iona. Walter Bower was the abbot of the Augustinian community on the island of Inchcolm in the Firth of Forth. Inchcolm, of course, means ‘Island of Columba’. The cult of Columba, and therefore the history of Iona and its associated meanings, must have been important to Bower and the canons of his island community. It is in Bower’s Scotichronicon that we find the first clear occurrence of the spelling Iona for our island. He discusses Iona as a ‘royal island’:

Quarum insularum hec que secuntur dicuntur et sunt insule regales, videlicet Iona sive I vel I Colmekil in qua sanctus Columba construxit monasterium que usque ad tempus Regis Malcolmi viri Sanct Margarite fuit sepultura Regum Pictiuie et Scocie (Scotichronicon I, 6).

Of these islands the following are called, and are, royal islands, that is Iona, or I or I Colmekil, in which St Columba built a monastery which was the royal burial-place of the kings of Pictland and Scotland.

At this point of the Scotichronicon, in Bower’s own manuscript of the work, the name Iona is ambiguous. It could just as easily be read as Ioua because of the similarity of n and u in his handwriting. What more or less forces us to read it as Iona is the appearance of the name later in Scotichronicon (II, 10):

I, uel Iona Hebraice quod Latine Columba dicitur, sive Icolumkil ubi duo monasteria sunt fundata per Sanctum Columban, unum Nigrorum monachorum, aliud sanctarum monalium ordinis Sancti Augustini rochetam deferencium, et ibi refugium.

I, or Iona in Hebrew which is what Columba means in Latin [i.e. ‘dove’], or Icolumkil, where there are two monasteries founded by Saint Columba, one of black monks, the other of holy nuns of the order of Saint Augustine who wear the rochet; and there is a refuge there.

The striking thing in this sentence is that not only is the name Iona absolutely clear and unambiguous in Bower’s handwriting, with a perfectly formed n, but the passage itself clearly indicates that Iona was intended, because Iona is the Hebrew word for ‘dove’, as Bower says, which is Columba in Latin. Bower took most of this sentence from Fordun’s early Chronicon which, as we saw above, says:

Insula Hy columbkille, ubi duo Monasteria sunt, unum Monachorum, aliud Monialium, ibidem itaque refugium (II, 10).

the island of Hy columbkille, where there are two monasteries, one of monks, another of nuns, and there is a sanctuary there

But Bower adds interesting details of his own: what orders the monks and nuns belong to, for example, and this remark about the alternative name of the island. Where Fordun called it Hy Columbkille, Bower adds other forms of the name, I and Iona. Given that he knew that Iona is the Hebrew form of Columba, and repeated that observation in this passage about the island, we may imagine that it was this connection between the name of the island and the name of the saint which ‘motivated’ his rendering of the island name as Iona. This is the first clear reference to the island formerly known as Ioua as Iona.

It seems that Walter Bower himself may have invented the new name, Iona, for our island, his misreading of Ioua motivated by his reading of Adomnán’s Vita Columbae where Iona appears as a translation of Columba. If so, his misreading seems to have caught on fairly quickly. As we have seen, manuscripts of Fordun’s Chronica which post-date Bower’s work use this spelling. And when Andrew Wyntoun’s Original Chronicle cites the couplet from the Verse Chronicle which we cited above, he spells it Iona. At least this is how it appears in the earliest manuscript of his work, though that seems to date from the end of the fifteenth century, so as a manuscript it post-dates Bower (even though Wyntoun was writing at the beginning of that century – he died circa 1422). As Wyntoun and Bower were both Augustinian canons, and lived a mere 22 km away from each other, in Loch Leven and Inchcolm respectively, it is more than likely that these two historians knew each other. The spelling in the Wyntoun manuscript may have arisen from Bower’s personal influence on Wyntoun; or it may be that the Iona spelling was not in Wyhtoun’s original text, but appeared in the manuscript a few decades later under Bower’s influence.

It must be stressed that this theory of the invention of Iona is an extremely fragile one. It would only take one manuscript with a clear reference to the island as Iona dating to before the 1440s to completely disprove Bower’s motivated invention of the name. We have as yet traced no such reference.

Several other theories about the name Iona have been proposed in more recent centuries, though none of them hold water. The visitor of 1771, for example, suggested that ‘the island was dedicated to the Apostle John; for it was originally called J’Eoin, i.e. John’s Island, whence Iona’ (Sharpe, ‘Iona in 1771’, 183). As we have seen, the name existed for many centuries with no letter n in it, so the explanation involving ‘John’ is interesting but wrong. We may also add that the form J’Eoin meaning ‘John’s Island’ depends on another mistaken notion: that the Gaelic name Í meant ‘island’. There certainly was a word í meaning ‘island’ in Gaelic, but it was a loan-word from Old Norse ey ‘island’, and that means the loan cannot have predated circa 800 AD, when the Norse raiders first came west, and probably a good deal after that. But Iona had been called Í or Ia long before the Norsemen arrived.

Another entertaining story about the origin of the Gaelic island-name first appears in the sixteenth century as a kind of pun. Manus O’Donnell’s Life of Columba has him sailing from Ireland to Scotland and spotting the island:

Et ni haithrestar a scela osin amach noco rancutar an t-oilen darub ainm hÍ Colaim Cilli aniugh, & ann aspert an rand-sa:

Dochím hÍ, bendacht ar gach suil docí,

Anté doní les a cheili, ass e a las fene doní. (O’Donnell 1532, 200).

And the story tells nothing more from then on until he came to the island which is called Í Colaim Cille today, and then he uttered this verse:

I see her (or Í). A blessing on each eye that sees.

The thing one does to his neighbour, it is that he does to himself.

This tale is taken up by Martin Martin, who is more explicit about the nature of the pun, presumably because he is writing for non-Gaels who might not otherwise understand it:

That Natives have a Tradition among them, That one of the Clergy-Men who accompanied Columbus in his Voyage thither, having at a good distance espcied the Isle, and cry’ed joyfully to Columbus in the Irish Language, Chim i, i.e. I see her: meaning thereby, the country of why they had been in quest: that Columbus then answer’d, It shall be from henceforth called Y (Martin 1703, 256).

There is one other misunderstanding of the name Í which is worth attending to. There is a Gaelic word í which simply means ‘island’. It has been suggested that this might be the origin of the Gaelic name of Iona, which is also Í. Thus, the Dictionary of the Irish Language under the word Í1 says that it means ‘island’ and is ‘the old Norse name of Iona’, and gives a series of early forms (hÍ, Hiae, Ia, Hí) which it seems to suggest derive from the Norse name. But this is quite wrong. Certainly there is a Gaelic word í meaning ‘island’, and it derives from the Old Norse ey ‘island’. But that cannot be the origin of the island-name, since we have references to Í and Ia (and Adomnán’s suffixed Ioua) which pre-date the arrival of Old Norse by two centuries. The name of Iona/Í cannot be related to the Old Norse word for ‘island’.

[1] Anderson, Kings and Kingship, 286-8. For digital images of the manuscript see https://parker.stanford.edu/parker/catalog/md506kt8712.

[2] William F. Skene (ed.), Iohannis de Fordun Chronica Gentis Scotorum (Edinburgh, 1871).

[3] ‘quod Ebreice dicitur Iona, grecitas uero peristera uocitat,et latina lingua columba nuncupatur.’

[4] Dauvit Broun, The Irish Identity of the Kingdom of the Scots (Woodbridge, 1999), 20-27.

Iodhlann Chorrach

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference: NM2681023223

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 13m

Elements: G iodhlann + G corrach

Translation: 'steep (stack-yard shaped) hills'

Iomair an Tòchair

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Antiquity, Relief

Grid reference: NM2842324722

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 27m

Elements: G iomair + G an + G tòchar

Translation: 'ridge of the causeway'

Description:

The feature itself is a 230 metre-long embankment, 10 metres wide, extending across the Lochan Mòr (q.v.). Its construction is not reliably dated. The RCAHMS report on the feature says, ‘While there is no evidence to show whether the embankment was constructed in the Early Christian or the medieval period, the labour involved was comparable with that required for work on the vallum, and the earlier date seems probable’ (Argyll 4, 35). The embankment may have been constructed as both a route across the Lochan Mòr and a part of the water management system associated with the mill that stood SW of the lochan on on the course of the burn now known as Sruth a’ Mhuilinn, ‘stream of the mill’, (q.v.).

The Douglas Map of 1769 shows a pair of lochs at what seems to be the lower part of Gleann Cùl Bhuirg (q.v.), which would otherwise have been a natural route from the abbey area to the west side north of the Machair. Those lochs, and the probably wet ground round about them, would have made a crossing of the island on that route problematic, except perhaps after a prolonged dry spell. This might explain the usefulness of a cross-island route over Lochan Mòr on the causeway, and from there to the north-west of the island along the valley lying to the south of Cnoc nam Bradhan, via Cobhain Cuildich (Argyll 4, 35). Subsequent drainage of those two lochs would have opened up another route to the west side a little to the south of the causeway, and perhaps made the causeway less important.

Iomair cha ‘n Iomair

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Coastal

Grid reference: NM2839123467

Certainty: 1

Altitude: m

Iomair nan Achd

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Antiquity, Ecclesiastical, Relief

Grid reference: NM2873224862

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 24m

Elements: G iomair + G an + G achd

Translation: 'ridge of the acts/decrees'

Description:

The local tradition associated with this name is that the ‘acts’ are a reference to the ‘Statutes of Iona’. In 1609, the Bishop of the Isles, Andrew Knox, summoned to Iona nine chiefs of his diocese to get them to agree to certain changes in their relationship with the established kirk and the crown, to changes in their way of exercising authority, and various other changes which, it was hoped, would bind them more closely into the kingdom and rectify various ‘abuses’. The choice of this site for such a gathering would not be at all surprising, especially given its proximity to Taigh an Easbuig (‘the bishop’s house’) whose construction may be more or less contemporary with the event.

Iomair nan Rìgh

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Antiquity, Ecclesiastical, Relief

Grid reference: NM2856124447

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 22m

Elements: G iomair + G an + G rìgh

Translation: 'ridge of the kings'

Description:

Although the name Iomair nan Rìgh (and variants) can be traced back no further than 1771, the idea that there was a concentration of royal burials in Rèilig Odhrain can be found as early as 1549, when Dean Monro recorded that this ‘Sanctuarie or Kirkzaird’ contained ‘three Tombs of stanes formit like little chapellis’, one inscribed Tumulus Regum Scotiae (‘tomb of the kings of Scotland’), with forty-eight ‘crownit Scottis Kings, throw the quhilk this Ile has bene richlie dotit be the Scottis Kings’, and also a Tumulus Regum Hiberniae (a tomb of the kings of Ireland, containing four kings) and Tumulus Regum Norvegiae (a tomb of the kings of Norway, containing eight kings). Nothing of this monument as described by Monro, or anything like it, has survived. By the 1770s, Thomas Pennant found no sign of these burials ‘like little chapellis’ on his visit, but described a collection of burials with slabs, some of whose inscriptions could be discerned. The burial ground was somewhat tidied up in 1868, and the surviving grave-slabs ‘rearranged and enclosed by a rail’ (Sharpe 1995, 278).

James Fraser has shown that the tombs mentioned by Monro were ‘wholly inspired by, and a by-product of, late medieval book-learning’ (2016, 10), and demonstrates that the legend of the burial of a whole sequence of early medieval Scottish kings arose from twelfth-century political concerns, and the need to establish the authority of the sons of Malcolm III and Queen Margaret against rivals (with the creation of a new royal mausoleum at Dunfermline).

The few legible inscriptions on the stones from Rèilig Odhrain and in Teampall Odhrain commemorate various Lords of the Isles, four sixteenth-century priors of Iona (on a stone which, though it was found in Rèilig Odhrain, may not originally have lain there), Gillebrìde MacFhionghain (Gilbride MacKinnon) with his two sons Ewan and Cornebellus, and Finguine mac Cormaic with his son Finguine and another called Ewan. Another stone commemorates an unidentified Lachlan (Argyll 4, 219-35). The other funerary monuments are mostly dateable to the fourteenth or fifteenth century or later. There is not a single carving that suggests that it was made for the burial of a king of Scots.

We should note that the OS 6 inch 1st and 2nd edn maps record the name Tombs of the Kings at the site of Iomair nan Rìgh. It is a matter of judgement whether we should view this term, Tombs of the Kings, as a place-name at all, rather than one of those lexical items which appear on OS maps, such as ‘Post Office’, ‘ferry terminal’ or ‘standing stone’. Because of the lack of attested use of the name, it is discussed here rather than being given its own entry.

Iona Church

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Antiquity, Ecclesiastical

Grid reference: NM2849324243

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 17m

Elements: en Ì ~ Iona + SSE church

Translation: 'Iona church'

Description:

This was the parish church of the island, built in 1828. As noted by Mairi MacArthur (1990, 240):

After at least two centuries of intermittent pastoral care, the building of their own parish church and manse must have been a notable event for the people of Iona. It formed part of a Parliamentary scheme set up in 1823, with a grant of £50,000, to build extra churches in areas of the Highlands and Islands where very large parishes were served by a single minister … Thomas Telford furnished the plans and specifications for the whole scheme and directed the design work. The contractor for the area which included Iona was William Thomson. Iona was the smallest of the thirty-two churches erected and it followed Telford’s standard design, with reduced wall and window height, but without a central rear wing or a gallery. The material used was pink Ross of Mull granite.

There is a local tradition that it was built on the site of the now lost Cill Chainnich ‘church (or burial ground) of [Saint] Cainnech’, a tradition recorded by Bishop Reeves in his visit to Iona, when he also observed (or was informed?) that ‘the foundations were removed some years ago, and a few tombstones are all that remain to mark the cemetery’ (1957, 417, Argyll 4, 243-44).

Iona Cottage

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV)

Classification: Settlement

Grid reference: NM2852624025

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 6m

Elements: en Ì ~ Iona + SSE cottage

Translation: 'Iona cottage'