June 2025: Ì / Eilean Ì | Iona

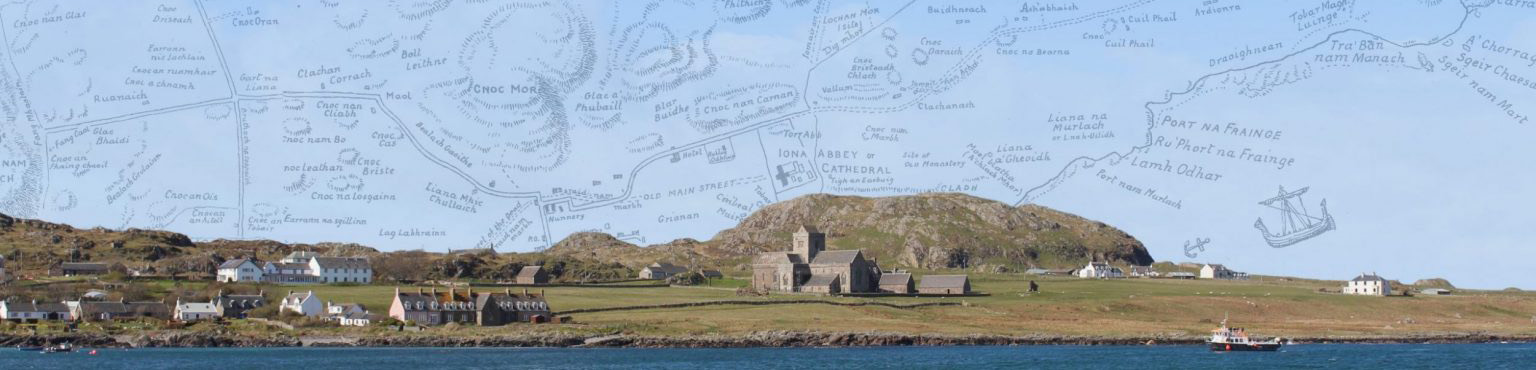

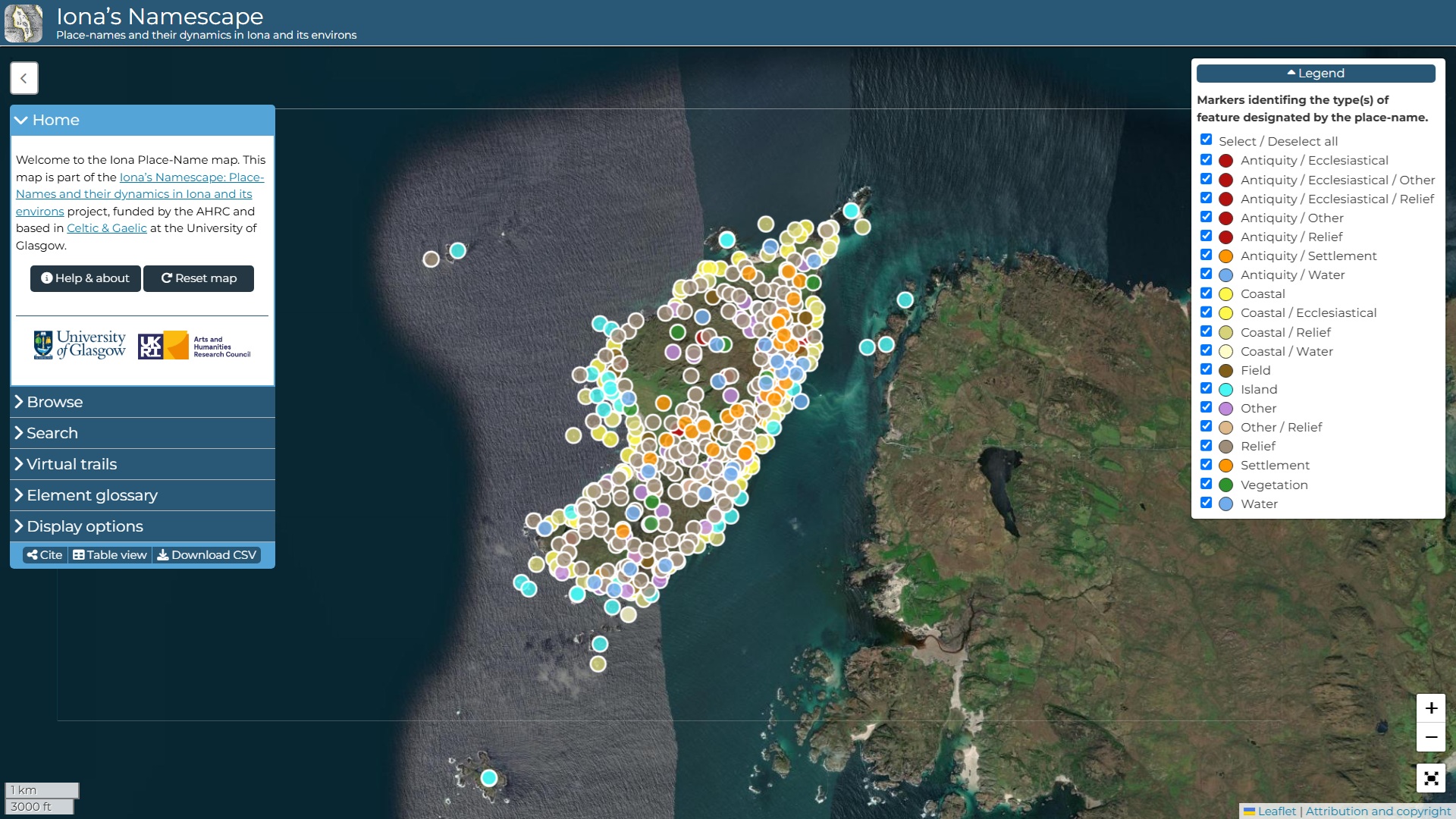

Our final Name of the Month, as the Iona’s Namescape project comes to the end of its funded period, is, of course the name of the island itself. In Gaelic a very simple name (Ì, also Eilean Ì), it has had a long and complicated history of the name being changed, augmented and reinterpreted, across several languages. For all that, we are no nearer to knowing what its original name in Gaelic means. It is quite likely that, like a number of other Hebridean island names, it is very ancient, and perhaps survives from a language spoken in Scotland long before Gaelic or the other Celtic languages. For more details on this and many of Iona’s other place-names, see the Iona Place-Name Map.

May 2025: Raven’s Crag

This name seems to be unknown outside the rock-climbing community, but among climbers it is a well-known rock with a number of routes of varying difficulty ascending different parts of it. The UK Climbing website lists and describes several routes, and has generated a list of interesting names (as climbers often do) for the different routes.

For further evidence of ravens in Iona’s toponymy, see Sgùrr an Fhithich.

See entry in the Iona Place-Name Map for more information about this name.

April 2025: Clach a’ Bhainne ‘the milk stone’

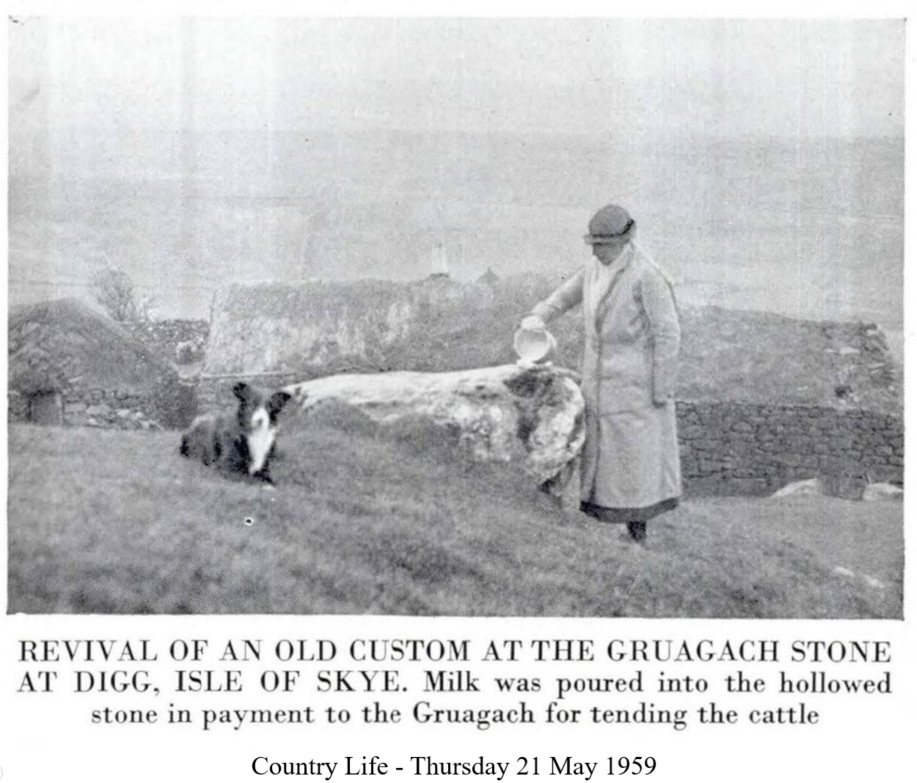

Two different supernatural beings associated with the protection of cattle are found in Iona’s place-names. First, the Glaistig, according to Alasdair Alpin MacGregor (1936, p. 64) lived in the Staonaig area, ‘in a hollow rock near at hand. For this Glaistig the Iona women at milking-time each evening poured a little milk on what is still pointed out as the Glaistig’s Stone.’

Second, the Gruagach, according to Alexander Carmichael (Carmina Gadelica vol. 2, p. 306) was ‘a supernatural female who presided over cattle and took a kindly interest in all that pertained to them. In return a libation of milk was made to her when the women milked the cows in the evening. If the oblation were neglected, the cattle, notwithstanding all precautions, were found broken loose and in the corn; and if still omitted, the best cow in the fold was found dead in the morning.’ He goes on to note that Iona was one of the places where he had seen such a stone.

The stone in question seems to refer to a rock known locally as Clach a’ Bhainne or ‘the milk stone’. According to Mairi MacArthur (1990, p. 273) it ‘lay on the edge of the eighteenth century village, a few yards from the site of the present day telephone boxes’. We have been unable to find any traces of such a stone in the present-day village and it may have been moved or covered by tarmac. If anyone has information about this stone, or other milk stones, please get in touch!

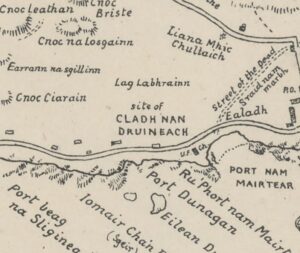

March 2025: Cladh nan Druineach

Cladh nan Druineach, often incorrectly interpreted as ‘burial ground of the druids’. For example, Richard Pococke in 1760 gave it as ‘the Druid’s Burial-place’ and William Douglas gave it as ‘Druids Burial Place’ on his 1769 Estate map.

Cladh nan Druineach, often incorrectly interpreted as ‘burial ground of the druids’. For example, Richard Pococke in 1760 gave it as ‘the Druid’s Burial-place’ and William Douglas gave it as ‘Druids Burial Place’ on his 1769 Estate map.

However, as Katherine Forsyth argues, nan druineach may in fact refer to embroideresses (cf. OG druinech), giving us ‘burial ground of the embroideresses’. Might this name indicate the presence of female artisans responsible for the production of church textiles on Iona in the early Middle Ages?

February 2025: Glas-Eilean

January 2025: Tràigh nan Sìolag | Sandeels Bay

In light of the discussion about the fishing of sandeels mentioned above, it is worth noting that Martin Martin (1703, p. 58) described the Hebridean practice of catching what was likely sandeels as follows: ‘the Islands do also afford many small Fish call’d Eels, of a whitish colour; they are picked out of the Sand with a small crooked Iron made on purpose.’ Perhaps it was this practice that prompted the coining of this name?

December 2024: Tràigh Bàn (nam Manach)

November 2024: Tobar na Gaoithe Tuath

A windy name for a windy month: Tobar na Gaoithe Tuath ‘the well of the north wind’, now just a barely visible pool of water (see image).

According to Seton Gordon (1920, p. 49) ‘the people of Iona were wont, after the close of the harvest, to set out for Glasgow in their smacks, carrying with them the produce of the island. For this passage a steady northerly wind was all-important, so that before they set sail the voyagers made their way to a certain well on the island, stirred its waters—the while uttering mysterious sentences in the Gaelic, which have now unfortunately been lost—and asked the Spirit of the Well that the wind might be favourable to them. Afterwards they proceeded to another well, going through the same ceremonies here and asking for a steady and continuous south wind to bring them back to lona. The two wells are known as “Tobar na gaoithe tuath ” and “Tobar na gaoithe deas,” that is, “the well of the north wind” and “the well of the south wind.”‘

Mairi MacArthur notes that Malcolm Ferguson who spent a week on Iona in 1893 ‘was told of wells of the four winds, though not their locations, and that a family whose forefathers had come with St Columba were blessed with the gift of raising a wind.’

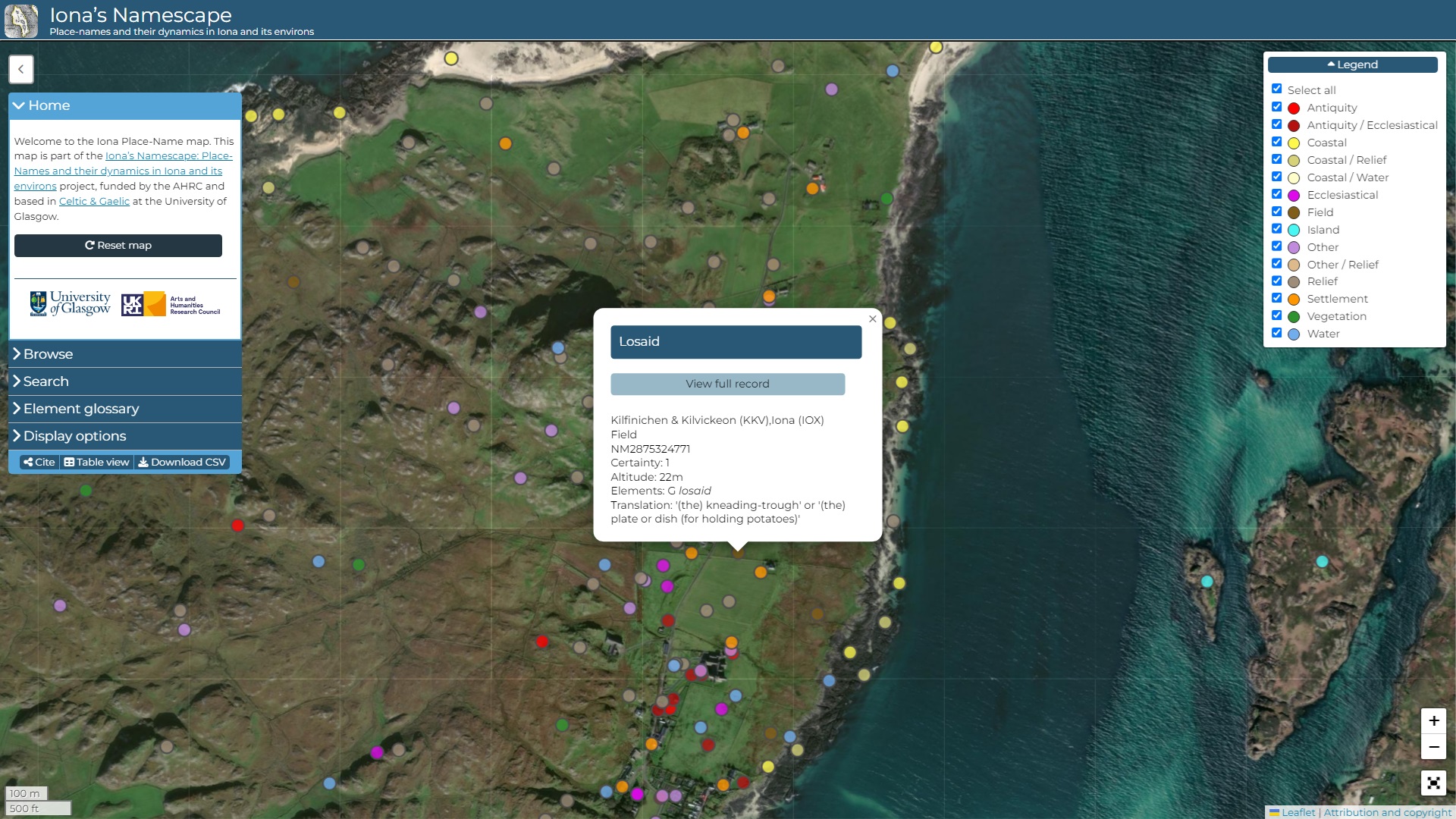

October 2024: Losaid

October, tattie holiday month. The name Losaid, referring to a feature located between Clachanach and Liana a’ Gheòidh, may have a surprising connection to potatoes. Gaelic losaid often refers to a kneading-trough, and is found as a place-name element in other parts of Scotland with this meaning (e.g. Lochbroom, Canna). However, the place-name Losaid on Iona may contain a local application of the word denoting ‘a plate or dish (for holding potatoes)’. In 1986 Dugald MacArthur noted that ‘the Losaid was known to be good for growing potatoes.’

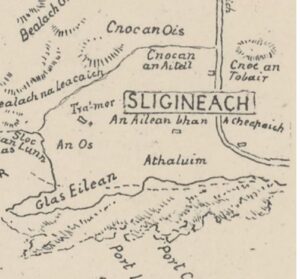

September 2024: An Àilean Bhàn & Greenbank

Two names for the same croft, known in local Gaelic as An Àilean Bhàn ‘the fair meadow’ and in English as Greenbank, reflecting the fine stretch of grassland around there above the shoreline south of Baile Mòr.

The Gaelic name was well known to Calum Cameron, crofter at Traighmor, when overhearing his elderly neighbour talking aloud on occasion: ‘If I’m alive next spring, and by God I will be, I’m going to plough the Àilean Bhàn’ (recorded 1985).

In the second half of the 19th century, a woman born in Greenock, Henrietta MacInnes (née Morrison), married an Iona local at the croft in the 1870s – though deaf from childhood she could speak, but knew no Gaelic. The English name Greenbank was coined to make it easier for her to pronounce the name of the croft. Check back to read more about these names in an upcoming blog post.

August 2024: Cobhain Cuildich

A throw back to one of the very first names discussed in our blogs HERE.

back to one of the very first names discussed in our blogs HERE.

Pictured is Cobhain Cuildich. The separate stone structure located ca. 30m to the north in the background of the image is described in Argyll vol 4 (p. 257): ‘an irregular-shaped enclosure, measuring up to 25m by 12m internally, has been formed in the lee of a massive rock outcrop which itself serves as a wall on one side … [It] is probably a sheep- or cattle-pen of no great antiquity.’

It seems rather odd that one has a name and the other, as far as we know, doesn’t. Does anyone know a name for this structure?

July 2024: Sìthean Mòr na h-Àird

One of the lesser-known hills on Iona containing the element sìthean ‘(fairy) mound’. Not to be confused with Sìthea n Mòr in the centre of the island, this name refers to a hillock located on the south-eastern coastline of Iona. The qualifier ‘na h-Àird’, referencing the nearby height of An Àird, has perhaps been added to distinguish this hill from the abovementioned Sìthean Mòr.

n Mòr in the centre of the island, this name refers to a hillock located on the south-eastern coastline of Iona. The qualifier ‘na h-Àird’, referencing the nearby height of An Àird, has perhaps been added to distinguish this hill from the abovementioned Sìthean Mòr.

There is no evidence for fairy-lore of the type associated with Sìthean Mòr to be found here. It is, however, worth noting that a local story associates the nearby ridge of Druim Dhùghaill with fairies. The tradition, as told by Donald MacFarlane in 1963 (TAD ID 17790) relates that: ‘A young man had a fairy sweetheart and a smith made him a steel arrow so that he could not be harmed while carrying it in his clothes. But he was to go to a wedding and changed out of his usual clothes. He went to hunt rabbits on the ridge till the wedding began but he never returned. His body was found next day. She had killed him. The place where he was found was named after him, Druim Dhughaill’ (trans. Mairi E. MacArthur 1990. The original recording in Gaelic has been digitised by Tobar an Dualchais ID17790). Could there be a connection?

June 2024: Clach Chùil

Clach Chùil ‘rock of the corner or nook’ is an imposing collection of rocks near Calbha in the north-western part of the island. It is described by Dugald MacArthur (TAD ID 84012, part 1, 40:45) as ‘a heap of large loose stones with considerable space into which sheep get jammed at times and into which small boys always like to climb’. It is worth noting that in the same recording he also corrects the Ordnance Survey which places the rock in the sea, describing it as ‘a small rocky island’, despite the rock in question being located ca. 50 yards above the high-water mark.

May 2024: Iomair nan Rìgh

May seems like a good month (for reasons which will become clear) to think about Iomair nan Rìgh, ‘ridge of the kings’ (NM285244). It is a kind of hump in the cemetery of Reilig Odhráin. In 1771 a visitor to the island wrote about it, reflecting a tradition that goes back to at least 1549: ‘the Ridge of the Kings (Imar na rioghran). Here the kings of Scotland are interred. … On the north side of the kings of Scotland the Norwegian kings are buried, and the Irish on the south.’ But James Fraser has argued that this legend about ‘the kings of Scotland’ being buried here was invented in the thirteenth century – a propaganda piece made for contemporary political reasons.

Bede tells us, however, that on 20 May of AD 685, Ecgfrith, king of Northumbria, was killed fighting against the Picts at Nechtansmere. Bede does not seem to know where Ecgfrith was buried, but Symeon of Durham, writing in the twelfth century, thought he knew: ‘His body was buried on Hii, the island of Columba’. This is not as unlikely as we might think. The Martyrology of Tallaght (which was partly composed on Iona) commemorates Ecgfrith (Echbritan mac Óssu) on 27 May. Does that date refer to the day his body arrived on Iona for burial?

And we may also remember that Ecgfrith’s half-brother, Aldfrith, who succeeded him in the kingship of Northumbria, had been studying ‘among the Gaels’ up to this point. In fact Bede tells us that he was in insulis Scottorum – in the islands of the Gaels – which must surely mean the Hebrides, and most likely Iona. We may not accept the idea that the kings of Scots were buried in Iomair nan Rìgh, but it is more than likely that Ecgfrith – and other kings of the Irish Sea world – were buried on the island, and Iomair nan Righ seems a likely candidate for their burials.

April 2024: Port nam Mairtir

April sees the Feast of the martyrdom of St Donnan of Eigg, on 17 April. Early medieval Iona seems to have had multiple feast-days celebrating martyrs, and so our thoughts have turned to Port nam Mairtir and the English name Martyrs’ Bay for the name of the month. It seems a straightforward set of names, but it has a couple of problems. One is whether they describe the same thing. The Gaelic Port nam Mairtir refers to the long-established landing place; Martyrs’ Bay seems to describe the whole seascape around it. The other is what is meant by the Gaelic mairtir here. While there are plenty of events in Iona’s history which might produce ‘martyrs’, that is victims of religious violence (in 806 or 986 for instance), a tradition persistent since the 17th century holds that this was the place where bodies which were to be buried on Iona were landed. This has led to the idea that the word maybe refers to relics of saints, rather than martyrs themselves. It’s a name which will have a very full exploration in our web resource, which we hope to launch soon.

March 2024: Fang Màiri

With last month having seen the 1500th anniversary of St Brigid’s death, and on International Women’s Day, it seems appropriate to say something about one of the most prominent female saints in the Gaelic world. However, commemorations to St Brigid are notably absent in the historical place-names of Iona. On the other hand, she is frequently associated with Iona in later Celtic Revival literature and art (for example, by Fiona Macleod/William Sharp and John Duncan). This, and more on the saint, will be discussed in several upcoming blogs on St Brigid and Iona.

This does not mean that women are absent from the namescape of Iona. Place-names commemorating groups of women (as in Bealach nam Ban ‘Pass of the Women’) as well as individual women abound. One such name is Fang Màiri ‘Mary’s Enclosure’, located on the lower, south-west slopes of Dùn Ì. In 1966 Dugald MacArthur described it as a ‘well cultivated enclosed green plot’, adding that ‘we don’t know who Màiri is’ (TAD part 2 1:55). It is interesting to note that despite the consistent recording of the name in Gaelic, local pronunciation seems to be closer to English ‘Mary’ than Gaelic ‘Màiri’.

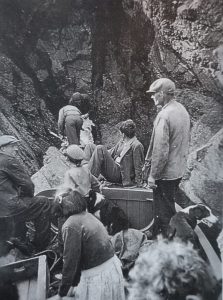

February 2024: The Marble Quarry

The only place-name in our corpus without a Gaelic (or Gaelicised) form on record as early as the 18th century is The Marble Quarry, located at the south-eastern end of Iona.

It first appears in 1790 in a report by Mr R.E. Raspé who refers to the site as the Marble Quarry. His survey led to the establishment of the ‘Iona Marble Company’ in the 1790s. This proved a short-lived venture; by 1794 ‘the Company’s storehouse in the village had been converted into a schoolroom.’ (Argyll vol. 4, pp. 254-6).

Interestingly, despite the quarry only having an English name, two Gaelic place-names, Tobhta nan Sassunaich ‘Ruins of the Lowlanders (Englishmen)’ and Taigh nan Gall ‘House of the foreigners’, both referring to accommodation quarters located above the quarry, give us some insight into the background of the workers at the quarry. The names likely reflect the fact that they predominantly consisted of English-speakers.

January 2024: Eilean Chalbha & Calva

Calbha~Calva appears in multiple place-names located in the north end of Iona. Eilean Chalbha (Grid reference: NM280261), an island just off the northern Iona coast, is undoubtedly the original feature referenced in an Old Norse place-name, *Kalfey ‘calf-island’. The name likely marks the island as a smaller feature connected to a larger one (i.e. the calf of Iona).

Calbha~Calva appears in multiple place-names located in the north end of Iona. Eilean Chalbha (Grid reference: NM280261), an island just off the northern Iona coast, is undoubtedly the original feature referenced in an Old Norse place-name, *Kalfey ‘calf-island’. The name likely marks the island as a smaller feature connected to a larger one (i.e. the calf of Iona). The name has been transferred to several other features on Iona, most notably the names of two of the crofts that formed part of the island re-organisation by the 5th Duke of Argyll in 1802. Typically referred to as Calva, the area provided good arable and pasture for cattle. The foundations of two houses, with adjoining stackyards, were still visible in the 1980s (see image).

The name has been transferred to several other features on Iona, most notably the names of two of the crofts that formed part of the island re-organisation by the 5th Duke of Argyll in 1802. Typically referred to as Calva, the area provided good arable and pasture for cattle. The foundations of two houses, with adjoining stackyards, were still visible in the 1980s (see image).

December 2023: St Martin’s Cross

November 2023: Dubh-Sgeir

The cluster of skerries located off the south-western coast of Iona have been named in various ways on different maps. This can perhaps partially be explained by tidal shifts, but there is nevertheless a notable discrepancy between the location of Dubh-Sgeir ‘Black skerry’ (NM250218) recorded on the Ritchie (1930) map and the 1st ed OS (1881) map. To complicate matters, the 1859 Admiralty Chart for Iona records a completely different name – Sgeir mor – a name which is absent from the other maps. Do you know more about these skerries? Get in touch here or via Twitter!

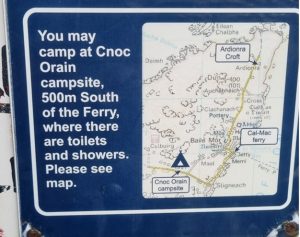

October 2023: Cnoc Odhrain

The classic Powell and Pressburger Hebridean-set film “I Know Where I’m Going” (1945) has been re-released this month in cinemas. In it, the heroine is trying and failing to get to the fictional island of Kiloran, somewhere off Mull. To celebrate the re-release, our Name of the Month features one of Iona’s many names containing the saint called Odhran or Oran. Although there is no Kiloran here (unlike on Colonsay), Cnoc Odhrain is a small hillock lying near the routeway from the village to the Machair. It has given rise to the name of the nearby settlement, anglicised as Cnoc Oran and sometimes Cnocoran. Why Odhran should have been associated with this hill is uncertain, but he is a frequent figure in Iona’s landscape. For more reflections on the saint, see Gilbert Márkus’s blog.

September 2023: Tobar na h-Aoise

A newly released collection created by designers Maeve Gillies and Mhairi Killin features jewellery inspired by the legacy of the Ritchies. You can find their collection here: https://www.ionamyheart.com/. One of their pieces is named after a place on Iona which is frequently mentioned in our sources – Tobar na h-Aoise ‘The well of age’, located near the summit of Dùn Ì.

The name has been translated in many different ways and has been attached to multiple traditions from the 19th century onwards. Beginning with Reeves (1857), who gives a literal translation ‘Well of age’, by the 20th century authors like Fiona Macleod (William Sharp) (1912) and Shedden (1938) translated the name as ‘The fountain of youth’ and ‘The wishing pool’ respectively. Trenholme (1909) recounts one of the traditions connected to such translations: ‘Local tradition says it was believed in of old as a magic well which could restore lost youth to a woman bathing face and hands in its waters before sunrise, the proper incantations, no doubt, being also necessary.’

August 2023: Uamh an t-Sèididh

Uamh an t-Sèididh, Uamh Spùtaich and the Spouting Cave are all names for the now famous cave on Iona. The cave is best known for the phenomenon described by Henry Davenport Graham as follows:

‘[It] consists of a deep cavern, into which, at all states of the tide, the sea continually rolls; and at a particular heigh of the tide the spouting commences. It is apparently caused thus:–A wave rolls into the cave, completely filling up the mouth, and, as it advances, the air within becomes violently compressed at the end of the rocky passage. Then the wave, losing its impetus, and the elasticity of the air causing it to expand as violently as it had been compressed, the sea is forced back out of the cave, and a great quantity of it finds a vent in a narrow crevice or chimney in the rocky roof, through which it rushes with great force, throwing up into the air several tons of water’

In an upcoming blog, we will try to untangle the development of the different names for the cave and how it has become embedded in the tourist experience of Iona.

July 2023: Gàrradh Marsaili

Who is commemorated in the name Gàrradh Marsaili? It refers to a small green patch located on the road leading from the Nunnery to the Abbey. Was she a woman in the village, perhaps an older woman or one who had lost her husband and was on her own – but still needed a small patch of ground to grow potatoes or keep a cow for milk?

After the village was laid out in the early 1800s, the occupants all had a right to graze a cow or keep a pig in the plots of land behind their houses. Later, four houses were also given a share of the bigger patch – Gàrradh Marsaili – after their own gardens were shortened. Do you know more about this name – get in touch here or via Twitter!

After the village was laid out in the early 1800s, the occupants all had a right to graze a cow or keep a pig in the plots of land behind their houses. Later, four houses were also given a share of the bigger patch – Gàrradh Marsaili – after their own gardens were shortened. Do you know more about this name – get in touch here or via Twitter!

June 2023: Tòrr an Aba

Two years ago today, on the Feast of St Columba (9th June), Thomas Clancy noted that there is a striking absence of the saint’s name in Iona’s namescape, especially in early place-names. However, one site which has become inextricably linked to Iona’s first abbot, despite the absence of Columba’s name, is Tòrr an Aba ‘The abbot’s hillock’. Referring to a small hill overlooking the Abbey, it is an apt location for the writing hut of St Columba described by Adomnán.

It took nearly 60 years of archaeology to confirm the dating of the site, beginning with the excavations by Charles Thomas in 1957. Adrián Maldonado writes that ‘In 1957 they exposed this area and found the remains of a small wattle hut. The burned down structure had been buried under pebbles, and the cross base had been set up over it.’ But it was not until 2016 that Ewan Campbell and Adrián Maldonado along with researchers from the University of Glasgow were able to confirm that the hut could be dated to between AD 540 and AD 650, plausibly placing it within the lifetime of the saint. Read more about the dating of the structure at Tòrr an Aba HERE.

May 2023: Slochd nam Biast

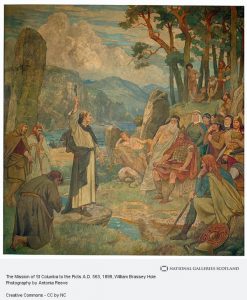

According to Mánus Ó Domhnaill’s Life of Colum Cille, when the saint arrived on Iona at Whitsun he encountered druids disguised as bishops who were promptly banished from the island by the saint.

Thomas Clancy writes about the resurfacing of such traditions relating to St Columba and druids in the 17th century in his forthcoming article, ‘Saints, Druids and Sea-Gods: imagining the past in Iona’s Namescape’. One account tells us of a place-name which is only recorded in a manuscript from 1776 (p. 87) as Slochd na m Biast.* We are told that:

The Druids possessed the Island on Columba’s landing; they were slain by his order, and the last of their slain Corpses thrown into a Pit called Slochd na m Biast, or the Hole of the beasts, meaning the Pagans or Druids.

The name is now obsolete and we have no indication of its location, but even if this were a place-name in use in the 18th century, there is no reason to assume that Gaelic biast ‘beast’ would necessarily have referred to druids, and it is possible that the 1776 account is a later construction. Rather, such a name may have referred to a site associated with cattle or other animals. Such an interpretation may be supported by comparable Iona place-names which refer to ‘cattle hollows’ such as Sloc Bò Phàidein ‘Pit of Pat’s cow’ (NM266216) and Sloc Bò Mhàrtainn ‘Pit of Martin’s cow’ (NM258227).

*In modern Gaelic this would be spelled Sloc nam Biast. For discussion of the representation of the word sloc as slochd, see Ó Maolalaigh 2005, p. 112.

April 2023

Sgeir an Òir ‘Skerry of the gold’ refers to a sea rock located just south of Eilean na h-Aon Chaorach.

It is not clear what the element òr denotes in this place-name. References to gold in place-names may sometimes denote especially fertile soil or the colouring of a feature, but there are also many instances of place-lore associating such places with buried treasure.

In the case of Sgeir an Òir, could the name be associated with a person rather than buried treasure? Mairi MacArthur (2002, 2nd ed, p. 216) writes: ‘the question, “Who was Pàraig an Oir?” [Peter the Gold], generally elicited the story of an Iona fisherman kidnapped by a passing ship and abandoned in a far-off destination. Eventually, with the aid of the ubiquitous Gaelic-speaking stranger, he is recompensed with a bag of gold pieces.’

Whether such stories of a kidnapped fisherman are rooted in reality or not, might this rock have become associated with the fortunes of Pàraig an Òir in local tradition?

March 2023

Notably, in a song by James Campbell which survives in oral tradition, Iona is described as Ì Phort Rònain (‘Iona of Port Rònain’) (transcribed in MacArthur 1990, p. 253).

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

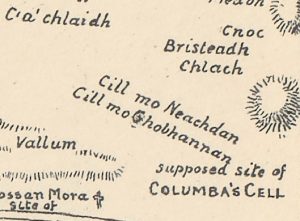

As noted by Thomas Clancy in a previous blog, St Columba is strikingly absent from Iona’s Namescape and place-names containing ‘Columba’ are usually relatively recent, and almost invariably in English rather than Gaelic. One such name is given to the large boulder located in a field north of the Abbey, recorded on Canmore (ID 347478) as St Columba’s Table (Grid reference: NM289249). How early this name attached to the stone is not clear.

The boulder is known in Gaelic as A’ Chlach Mhòr ‘The big stone’, but its association with St Columba may stem from 19th-century antiquarian identification of it with a stone mentioned in a medieval text, the preface to the hymn Altus Prosator. The 19th-century writers quoted one version of this story, which gives the name of a stone as Moel-blatha:

“Then Colum Cille lifted up the sack from the stone which is in the refectory in Iona, and this is the name of the stone: Moel-blatha,

and good fortune was left on the food which would be placed on it.”

Earlier versions of this story, however, call the stone Bláthnat. The precise meaning of these two much earlier names is not clear; neither is it completely clear that A’ Chlach Mhòr is really the stone mentioned in the story! But it does seem that this medieval anecdote somehow lies behind the modern English name of ‘St Columba’s Table’.

November 2022

This month’s Name of the Month is Crois Mhàrtainn / St Martin’s Cross, named after St Martin of Tours whose feast day is 11th November.

Devotion to St Martin in the early medieval Iona community is attested by Adomnán in his Life of Columba on several occasions. In VC III.12 we are told that the name of St Martin was included in the regular liturgical prayer. The story of Columba’s head being surrounded by a ‘radiant ball of fire’ in VC III. 17 also has close parallels with the episode described by Gregory of Tours (p. 31) in which a fire ‘burst from the top of the blessed Martin’s head’. It is worth noting that despite this early evidence for devotion to St Martin on Iona, the name of the cross is not necessarily early medieval.

The name is first mentioned in the late 17th century. Martin Martin who visited Iona during his journey to the Western Isles in c1695 describes the cross as follows: ‘Near St. Columbus’s Tomb is St. Martin’s Cross, an entire Stone of eight Foot high’. The name is first recorded in Gaelic in 1771 as Crois Mhartain.

October 2022

A’ Chorrag ‘The Finger’ (Grid Reference: NM294261) is a long finger-shaped rock jutting into the sea at the northern end of Tràigh Bhàn.

September 2022

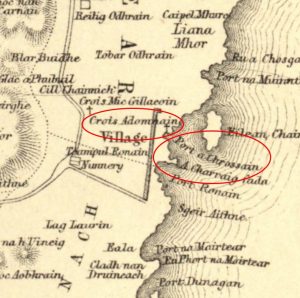

Saint Adomnán, ninth abbot of Iona, is commemorated – directly and indirectly – in two related Iona place-names. Port Adhamhnain ‘Port of Adomnán’ and Port a’ Chroisein ‘Port of the little cross’ both refer to the same inlet (Grid Reference: NM286240; Port a’ Chrossain on Reeves’ map). The names appear to be associated with a nearby cross dedicated to the saint, located near the centre of Baile Mòr, but no trace of the cross can now be found. ‘Crois Adomnain’ is included on the 1857 map of Iona drawn for William Reeves (see image). Both Reeves and Alexander Carmichael record versions of these names which capture something more of the contemporary Gaelic pronunciation of the saint’s name than do the somewhat antiquarian spellings: ‘Crois Aodhannan’ (Reeves), ‘Port Aona’ain’ (Carmichael).

According to Carmichael ‘My intelligent informant–kindly old John Macinnes, now dead–said that his father remembered a beautiful sculptured cross standing immediately above the beach there. It is more than probable that the cross was commemorative of Adamnan’. Mairi MacArthur notes that this John MacInnes’s father was born 1760 – and any sighting of a cross at this spot was likely to have been 18th-century, before the straight line of houses above the beach began to be built in 1802. There remains the question of why – so far as we know – no contemporary visiting antiquarians or travellers saw and described such a cross.

August 2022

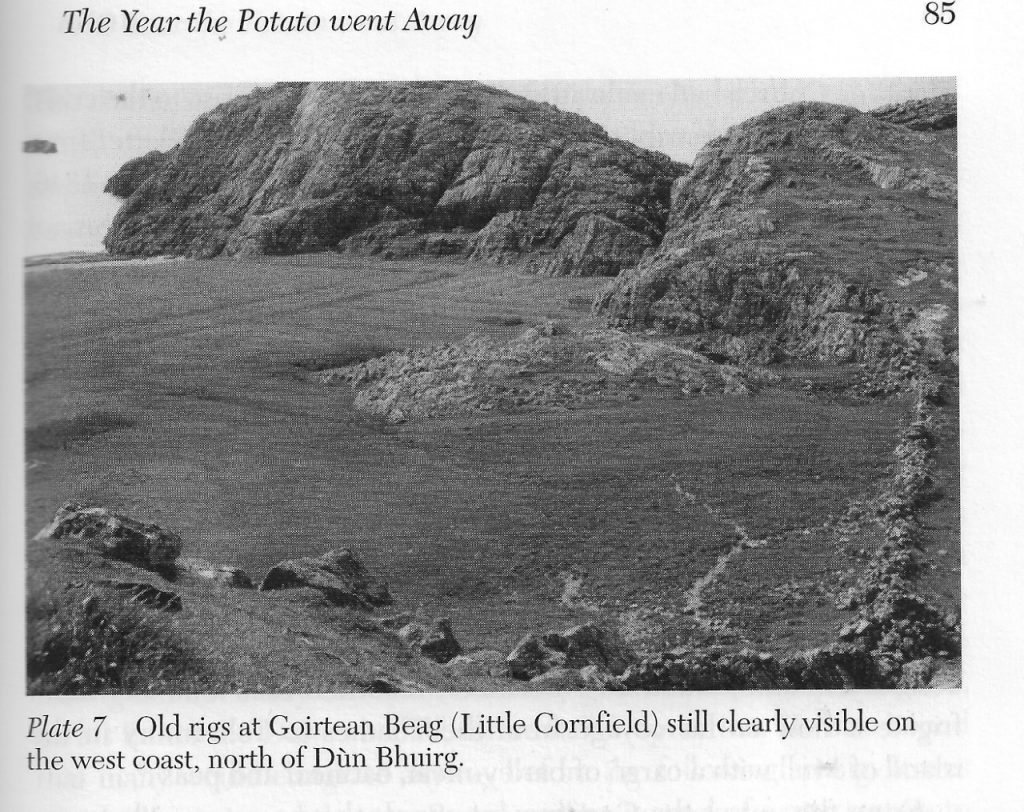

Beginning in August 1957 excavations led by Charles Thomas were conducted at Dùn Bhuirg (Grid Reference: NM265246). This is the second highest elevation on Iona, located near the western coastline of the island. The presence of an Iron Age fort on the hill means that it has received ample archaeological attention, but there has been little discussion of its name. The name Dùn Bhuirg likely contains an original Old Norse name with the element borg ‘fort, fortification, castle’. Gaelic dùn ‘fort, hill’ was later added to form the present (Gaelic) name.

The name has strong parallels across the Hebrides and comparable names can be found in Lewis, Harris, Uist, Barra and Mull. Many of these sites are referred to in local place-lore as the dwellings of fairies. However, such stories appear to be largely absent at Dùn Bhuirg on Iona. If you want to learn more about this name and its broader Hebridean context, don’t miss our next blog which looks at fairy lore in Iona place-names.

Do you know of any stories associated with Dùn Bhuirg on Iona? Get in touch! We would welcome input from anyone familiar with Iona.

July 2022

In July 1772 Thomas Pennant visited Iona. A few years later he published what would become one of the most influential early modern accounts of the island.[1]  One of the places he visited is known in Gaelic as Port a’ Churaich (‘The port of the coracle’), usually known in English as St Columba’s Bay (Grid reference: NM263216). Pennant is the earliest source to provide the English name ‘Bay of St. Columba’, describing the site as follows: ‘the landing place of St. Columba; a small bay, with a pebbly beach, mixed with variety of pretty stones, […] On one side is shewn an oblong heap of earth, the supposed size of the vessel that transported St. Columba and his twelve disciples from Ireland to this island’ (Pennant 1774, p. 297). Port a’ Churaich and St Columba’s Bay are arguably two of the most well-known place-names on Iona due to their association with the arrival of St Columba.

One of the places he visited is known in Gaelic as Port a’ Churaich (‘The port of the coracle’), usually known in English as St Columba’s Bay (Grid reference: NM263216). Pennant is the earliest source to provide the English name ‘Bay of St. Columba’, describing the site as follows: ‘the landing place of St. Columba; a small bay, with a pebbly beach, mixed with variety of pretty stones, […] On one side is shewn an oblong heap of earth, the supposed size of the vessel that transported St. Columba and his twelve disciples from Ireland to this island’ (Pennant 1774, p. 297). Port a’ Churaich and St Columba’s Bay are arguably two of the most well-known place-names on Iona due to their association with the arrival of St Columba.

The Gaelic name is recorded with many different spellings. Several sources (including the Ordnance Survey maps) have rendered the name as Port na Curaich following the modern gender (feminine) of the word curach ‘coracle’. We have here opted for the spelling Port a’ Churaich which better reflects local usage and seems to preserve an older masculine gender of the word. Some sources (see TAD track ID 17784 and MacCulloch 1819, p. 21) use the element curachan ‘little coracle’ with the Gaelic suffix –an (used to denote small size) added. In some accounts (see Nicolson here) the name of the boat in which St Columba travelled to Iona is referred to as An Liath Bhalaidh (‘The grey bulwark’). All of these points are important in their own right and will be discussed in more detail in future project publications.

[1] For more information about Thomas Pennant and his travels, visit The Curious Travellers project website.

June 2022

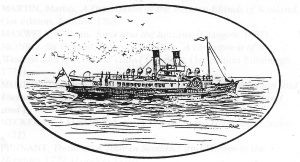

In December last year we looked at Brown’s Rock, named in commemoration of the shipwreck there in 1865. But this is not the only Iona place-name associated with a ship: Sgeir a’ Mhountaineer (Grid Reference: NM298262) is the local name for a skerry directly south-east of Eilean Annraidh where a paddle-steamer, the Mountaineer, nearly came to grief in the mid-1800s. Dugald MacArthur (born 1910) used to hear older people talk of how the ship hit the rock, began to take on water but was not grounded. The captain carried on south at full speed and ran her into Port nam Mairtear and safety.

Launched in 1852, the first Mountaineer was one of a series of classic steam-ships which brought visitors from Oban to Iona and Staffa each summer. She finally met her end off Lismore in 1889; a new ship, built in 1910, was also named the Mountaineer.

Iona correspondents to the Oban Times and the North British Daily Mail regularly reported the first and last appearances of these ships each year, in early June and early October. They had become a signal for the turn of the seasons.

You can find pictures of the ship here: https://www.scottishshipwrecks.com/mountaineer/.

May 2022

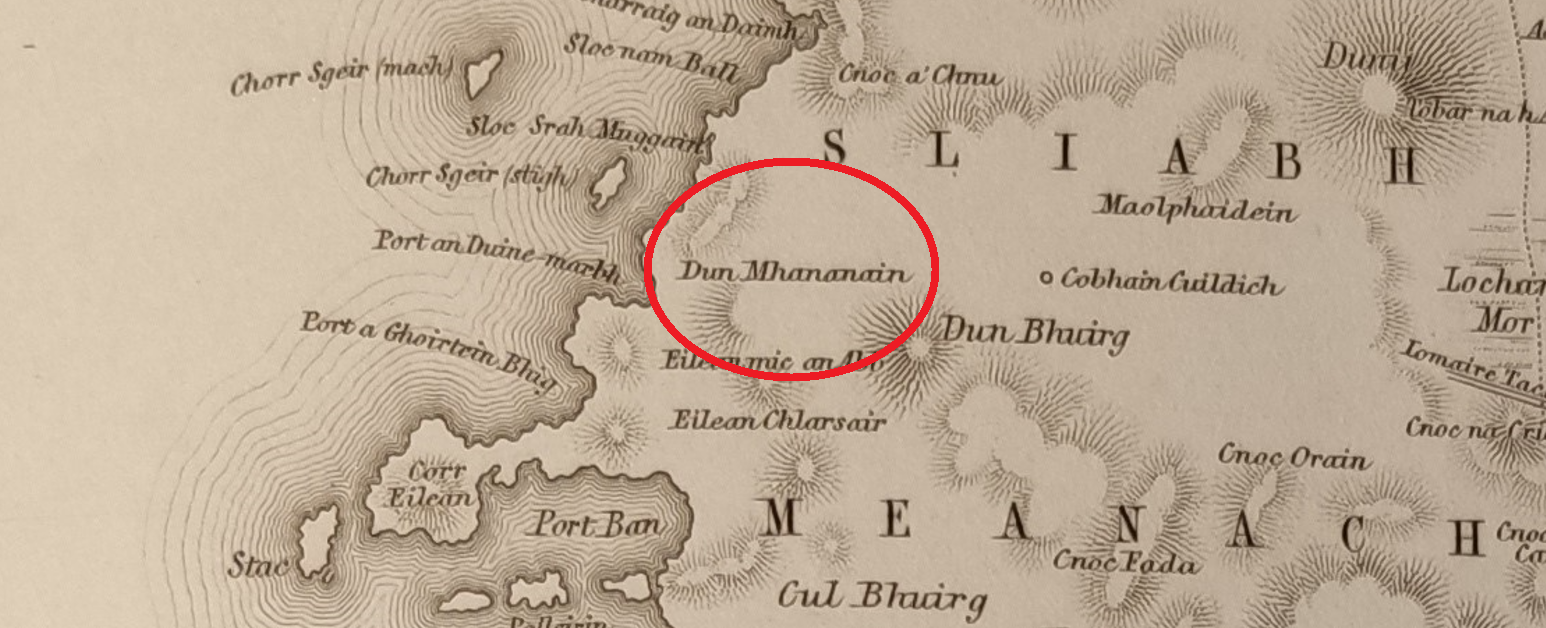

Dùn Mhanannain (Grid Reference: NM266250) is a coastal feature on the west side of Iona. The name as it stands seems to evoke a figure from early Gaelic stories, Manannán mac Lír. He is usually described in short-hand as ‘the god of the sea’, but his character and the role he plays in early Gaelic tales is much more complex than that.[1] A big question is – what is he doing here on Iona, being commemorated in the landscape?

Dùn Mhanannain (Grid Reference: NM266250) is a coastal feature on the west side of Iona. The name as it stands seems to evoke a figure from early Gaelic stories, Manannán mac Lír. He is usually described in short-hand as ‘the god of the sea’, but his character and the role he plays in early Gaelic tales is much more complex than that.[1] A big question is – what is he doing here on Iona, being commemorated in the landscape?

Before we try to answer that, it is worth wondering whether he is really there at all in the first place. The name first appears (as Dun Mhananain) in 1857 on the map and list drawn up by William Reeves (image above).

But not long after this the Ordnance Survey has a rather different name: Dun Manamin. You could argue that this is just someone’s misreading of Reeves’s map, but it is not a completely obvious misreading. On the other hand, it is not straightforwardly a representation of a Gaelic word either. The word it most resembles is meanmain (‘spirit, boldness, bravery’) as in the Gaelic term mac-meanmain, ‘imagination’. This is pronounced something a bit like ‘manamin’. So, could we imagine a landscape feature called ‘the fort of spirit / bravery’? It sounds overly romantic, and not much of an improvement on the god of the sea! There is much to work out here: a fuller blog on this name will follow.

In the meantime, it seems likely that this may be an antiquarian name of some sort, whether 18th or 19th century in origin. Does anyone know anything further about this site? Are you aware of any traditions relating to it—or alternative names?

[1] For a full account of this character, see Charles W. MacQuarrie, The Biography of the Irish God of the Sea from The Voyage of Bran (700 A.D.) to Finnegan’s Wake (1939) (Lampeter: Edwin Mellen Press, 2004).

April 2022

For April’s Name of the Month feature we are looking at another one of Iona’s many monuments (also see our May 2021 feature on Crois Brendain). Crois Mhic ‘IllEathain, or MacLean’s Cross in English (Grid Reference: NM 28544 24232), is a late 15th-century cross located on the road between the Nunnery and the Monastery. This location seems to originally have had three branching roads going in a southwardly direction, all still visible on the 1769 Douglas estate map. The name is first recorded in 1695 and likely commemorates the monument’s patron, a MacLean of Duart or Lochbuie (Argyll vol. 4, p. 237). MacLeans were closely involved in the late medieval monastery, as both patrons and personnel.

The cross is frequently mentioned by early modern travellers visiting Iona, sometimes in the context of the oft-repeated (and likely vastly exaggerated) statement that Iona once had 300 or 360 crosses, most of which were destroyed after the Reformation. The original statement seems to have referred to 300 stones with inscriptions in the possession of Fraser, dean of the Isles 1633 to 1680. [1]

Pennant (1772, p. 283) writes that it was ‘one of three hundred and sixty [crosses], that were standing in this island at the reformation, but immediately after were almost entirely demolished by order of a provincial assembly, held in the island.’

[1] MacArthur, E. M. 1995. Columba’s island: Iona from past to present (Edinburgh), p. 20.

March 2022

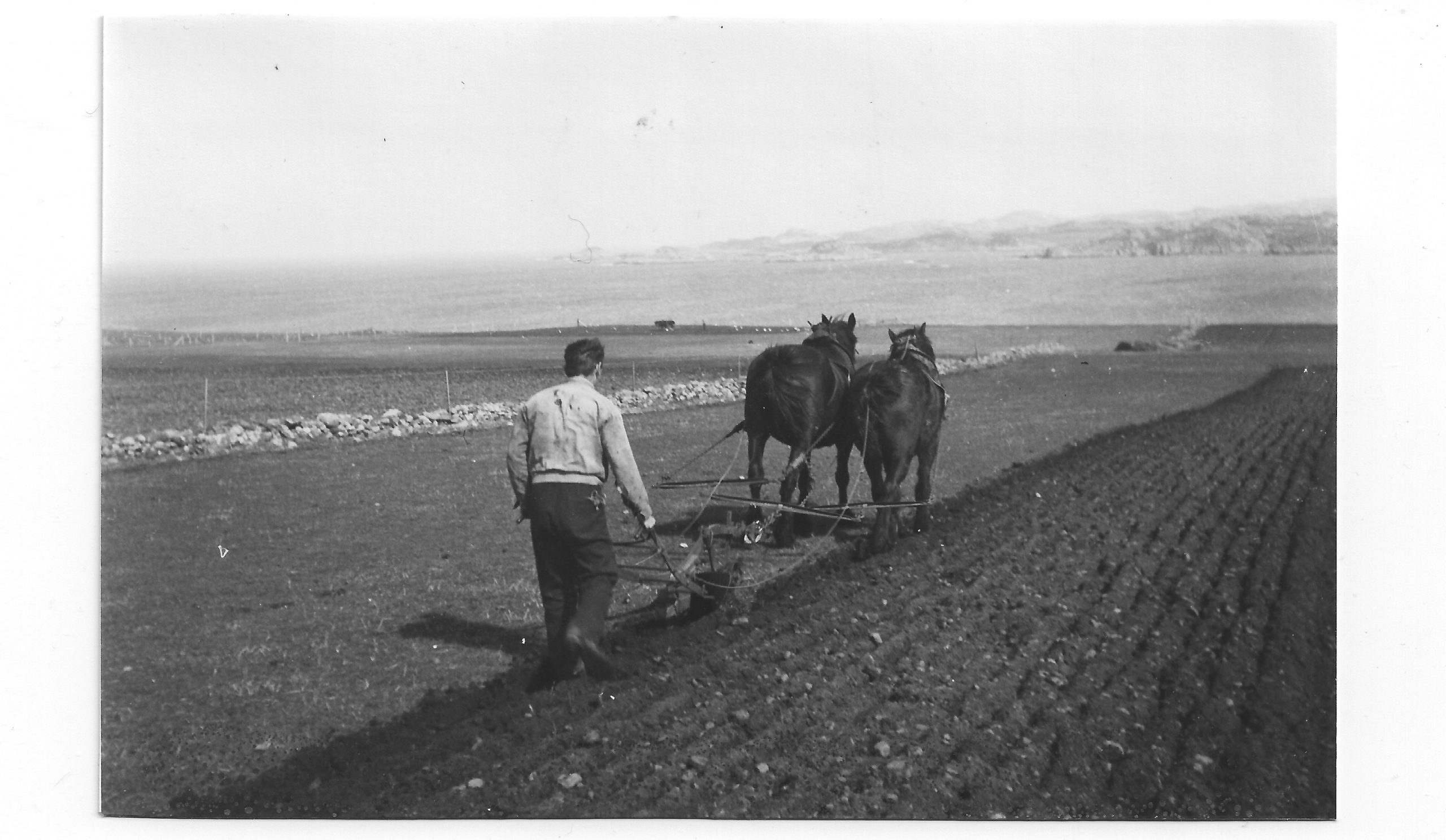

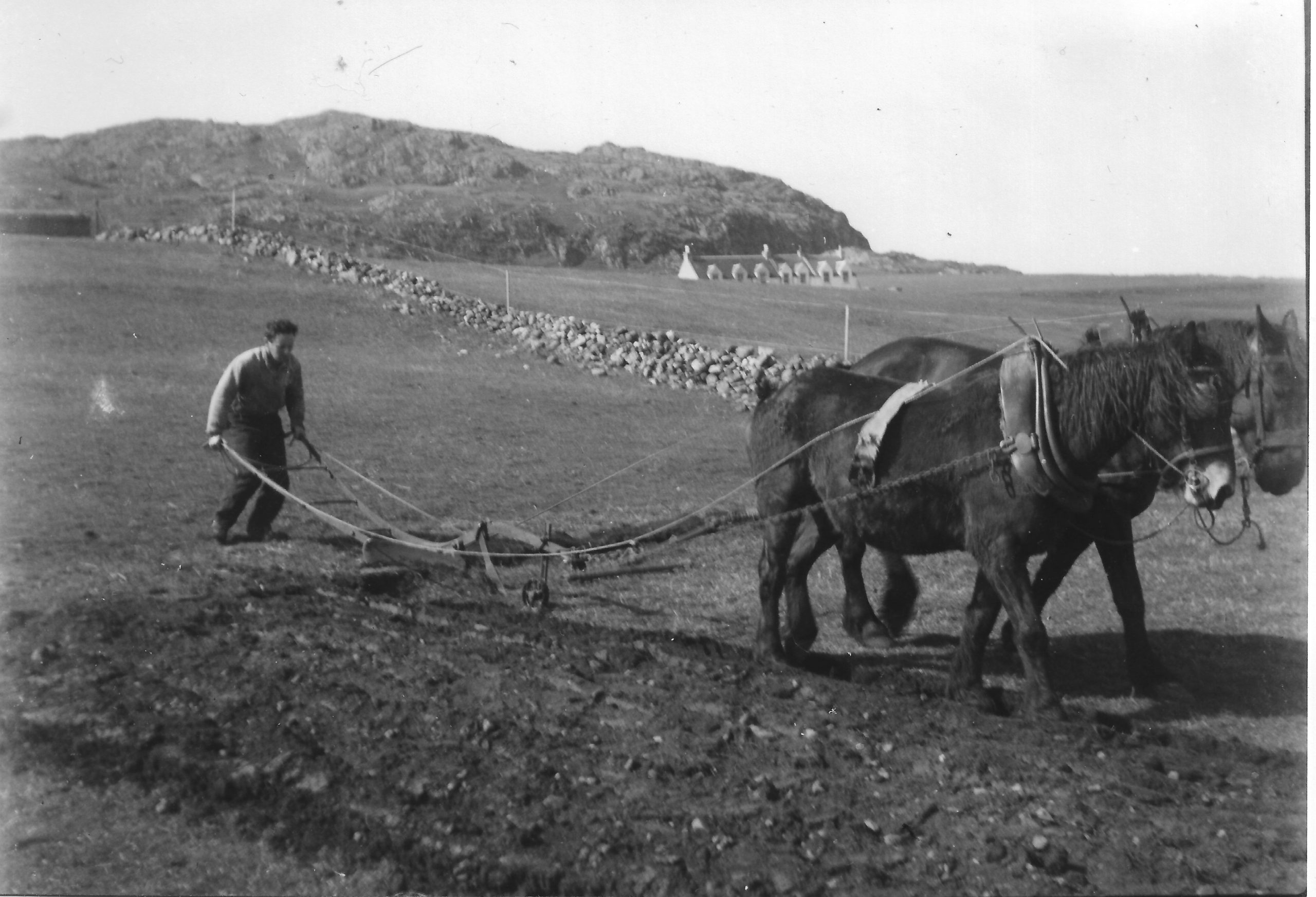

An Earrann Mhòr ‘The large share or portion’ (Grid Reference: NM289249) refers to a field located east of Clachanach. Spring is the season for ploughing, sowing and planting. The images show An Earrann Mhòr being ploughed in the Spring of 1944.

As is often the case, many of the field-names of Iona have now fallen out of use and are not recorded on most published maps. Other examples of the element earrann on Iona are Earrann Nic Lachlainn,[1] Earrann Dhubh na Maol[2] and Earrann na Sgillinn,[3] all located on the island’s arable land.

[1] Ritchie, A. & Ritchie, E. 1930. ‘The map of Iona. I Chaluim – Chille’ (Edinburgh: G. Stewart & Co. Ltd.), https://maps.nls.uk/counties/rec/6284.

[2] MacArthur, E. M. 1989. ‘The Island of Iona: aspects of its social and economic history from 1750 to 1914 vol. 2’ (Unpublished PhD Thesis: University of Edinburgh), p. 113.

[3] Ritchie & Ritchie, 1930.

February 2022

Recently featured in a film created by Niall O’Gallagher, Mhairi Killin & Michael Begg for the Spiorad an àite project (watch it HERE), we are taking a closer look at St Martin’s Caves (Grid reference: NM258227) for our February Name of the Month.

Despite its name, St Martin’s Caves refers to a passageway through the rock on Iona’s south-western coast, accessible at low tide. Toponymically, it is quite an interesting name due to its multiple co-existing names. It is now generally referred to by its English name, St Martin’s Caves, which is sometimes translated into Gaelic as Uamh Mhartainn (the form given on The Iona Community’s map of Iona) or Uamhan Naoimh Mhàrtainn.

It is worth noting that Reeves (1857) and Ritchie (1930) give the Gaelic name Sloc Cheann an Amair ‘gully at the head of the trough or channel’ for the small valley that runs down to the pebbly beach where the caves are located. Reeves does not mention the caves, but the Ritchie map places the English name ‘St Martin’s Caves’ offshore, beside the headland (see image).

A local nickname for the caves is The Galleries, the result of sections of the passage forming smaller caves with openings on the landward side, like windows. In his memoir of family holidays on Iona since 1934, Stuart Steele recalls that Stanley Service, another regular visitor, ‘led us to The Galleries, a popular name for the St Martin’s Caves which are still quite difficult to find’ (Memories of Iona, p.58, printed in 2019 for The Iona Heritage Centre).

It is possible that the association with the name Martin is connected to the nearby island Eilean Maol Mhartuinn (Grid reference: NM257227), a topic we will explore in more detail in an upcoming blog.

January 2022

Our name for this month is Shuna Cottage (Grid reference: NM285241) located on the village street in Baile Mòr. We’re posting this name in January to commemorate Alec and Euphemia Ritchie, who built, lived in and named the cottage in 1899. Their work provides a cornerstone for anyone with an interest in Iona and its names. In January of 1941 Alec and Euphemia passed away at Shuna Cottage within two days of each other. You can read more about them and their work here.

This is our first name of the month to feature a house name. Shuna follows a well-established pattern of naming houses from existing names and places, in this instance the island of Shuna south of Oban (Grid reference: NM766082). We also know why the Ritchies named the cottage after the island. Euphemia spent her summers growing up there with her brothers and sister, Bessie, who died at the age of twelve. As a result, she remembered the island particularly fondly, later writing ‘Shuna was never the same to us again and yet we loved it. I love our early island home more truly and deeply than any other place I have lived or am likely to live in.’ (Find the quote and more information in MacArthur, Iona Celtic Art, 2003).

December 2021

Brown’s Rock (Grid Reference: NM263236): On 31st December 1865, the ship Guy Mannering, sailing from New York to Liverpool, was blown off course and sighted off the Machair on the western side of Iona, where it met its end. The captain, Charles Brown, was the last to be brought ashore safely after five hours in the water. The people of Iona commemorated the event, and the ca ptain, by naming the reef where the ship was wrecked “Brown’s Rock”.

ptain, by naming the reef where the ship was wrecked “Brown’s Rock”.

The Receiver of Wrecks reported the following in January 1866: ‘Finding the ship drifting to leeward among rocks, where it was not likely they could save themselves, the captain thought it advisable to run her into Machair bay on the west side of Iona. As soon as the ship touched the ground she immediately began to break up.’

The inset image was taken by Fiona Kyle at the Machair shoreline earlier this year, at low tide – an intriguing possibility is that the timber comes from the Guy Mannering. Fiona’s great-great-grandfather, John Campbell of Culdamh, was one of the islanders who risked their own lives to rescue 19 crew and passengers.

November 2021

With the recent publication of an article on Viking Age Iona in Current Archaeology in mind (co-authored by two of our team members, Thomas Clancy & Katherine Forsyth, with Ewan Campbell & Adrián Maldonado), our November Name of the Month looks at one of Iona’s Norse place-names: Soa (Grid reference: NM244192), recorded as Soa Island on Ordnance Survey maps (see image below).

As the article shows, the pervasive belief that Iona’s importance became greatly diminished during the Viking Age is inherently problematic. Our hope is that further research into Iona’s Norse place-names will shed further light on this.

Soa (also recorded as Soay) is a well-attested island name in Scotland meaning ‘sheep island’. It represents Old Norse *Sauðey with sauðr ‘sheep’, reflecting its use for grazing purposes. This was noted by Dean Monro in 1549 who stated that the island is ‘verey guid for sheepe’. In fact, Soa is still used for sheep grazing, reflecting a continued link between its Norse name and current use.

Image credit: Many thanks to John MacInnes for providing this image of Soa.

October 2021

Cnoc Mòr (Grid reference: NM282241), meaning ‘Big hill’ is a conspicuous feature which separates the monastic lands from the area to the west. It is as simple as names get, but it is an important feature. As you climb the hill you reach a rocky stretch of land (see image) with very few place-names recorded on published maps. Are you familiar with this area and know of other names on and around Cnoc Mòr? Let us know!

September 2021

Sìthean Mòr (Grid reference: NM270235): In 1760 Bishop Pococke wrote to his sister that in the south-western part of Iona there is ‘a fine small green hill, called Angel Hill, where they bring their Horses on the day of St. Michael and All Angels, and run races round it’. Also known as Sìthean Mòr ‘Large (fairy) knoll’, many names and traditions are associated with the hill in question. This includes the celebrations described above, which would have taken place during Michaelmas (29th September).

Do you want to learn more about Sìthean Mòr? Make sure to check back for our next two blogs where we will explore this place and its names in greater detail.

August 2021

For this Name of the Month we have Liana Mhic Chullaich (Grid reference: NM283239) to mark the beginning of the harvest season. Gaelic liana ‘meadow, plain’ is frequently found in the names of fields on Iona, testimony to the island’s comparatively good agricultural land. Mairi MacArthur notes a conversation with Calum Cameron, Iona, in 1985 which sheds light on the origin of this place-name: “Archie MacCulloch was the first to be put out of a croft, where Liana Mhic Chullaich is. The field ran down to his byre, at the back of Mary Ann’s shop [Duart] and he also had grazing rights on Eilean na h-Aon Chaorach and Musimul.” No reason for the eviction is recalled but it must have happened before 1841, as no MacCulloch is listed in the Census that year.

Haymaking on Liana Mhic Chullaich around 1910, by then part of Maol farm tenanted by Hector MacNiven (centre). Image credit: Mairi MacArthur.

July 2021

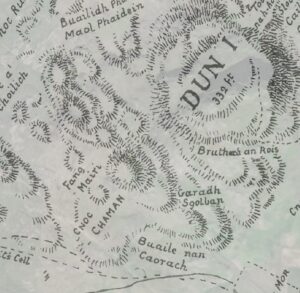

There are many references to plants and flowers in Iona’s place-names, so for this month, in the height of summer, we’re taking a closer look at one such name. Located on the south-eastern hillside of Dùn I, Bruthach an Rois (grid reference NM284251) probably means ‘Ascent of the rose(-bush)’ as suggested by D. Munro Fraser. As is the case with many of the place-names investigated as part of this project, the Ritchies’ map of Iona seems to be the only map to record this name.

When place-names contain references to flowers and other plants, the landscape can sometimes provide additional clues. If referring to a rose, it is in all likelihood the burnet rose (Gaelic Ròs Beag Bàn na h-Alba) which is well attested on Iona. It typically grows in rocky places and can be found above Sandeels Bay and Traighmore (Joyce Watson pers. comm.). Unfortunately, there are no traces of the flowers there now, but one possibility is that they grew here in the past, perhaps around the time when the Ritchie map was created.

The burnet rose features in several poems by prominent Scottish poets. One notable example is Hugh MacDiarmid’s ‘The Little White Rose’:

The rose of all the world is not for me.

I want for my part

Only the little white rose of Scotland

That smells sharp and sweet – and breaks the heart.

Special thanks to Joyce Watson for surveying the area and providing further information about the burnet rose.

Image credit: ©Anne Burgess and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

June 2021

June 2021

This month’s name marks the feast day of Iona’s founding saint, St Columba (9th June). St Columba’s Shrine Chapel is one of the few place-names on the island to directly commemorate the saint.

The reference in Norse sagas to a ‘Kolumkilla kirkju inni lítlu’ (the little church of Colum Cille) probably refers to this structure. Read more about this name and Columba dedications on Iona in our recent blog post HERE).

May 2021

Crois Brendain or St Brendan’s cross is included in William Reeves’ 1857 list of Iona place-names, but by the first half of the 20th century it was marked as obsolete by D. Munro Fraser in his appendix to the Ritchies’ Iona map (here spelled Crois Bhriannain). According to Reeves, the cross ‘stood near Tobar Orain, a little way east of the Free Church Manse [now the St Columba Hotel]. There is no trace remaining.’ If accurate, this means that the cross would have been located near the old Main Street in Baile Mòr, running from the Abbey to the Nunnery – perhaps it was originally a roadside cross.

The saint commemorated is likely St Brénainn m. Findloga whose feast day is 16 May. He also appears in many other Scottish place-names (for examples, see HERE).

April 2021

First in our ‘Name of the Month’ series is Uamh na Caisge (NM261217) found at the southern end of Iona in the sea cliffs to the west of Port an Fhir Bhreige. The name is translated by D. Munro Fraser and Reeves as ‘Cave of Easter’, but no associated traditions survive.

Do you know of other names for caves with Easter connections?