Mairi MacArthur writes:

“Cha b’e farainm a thug iad air an àite seo!” That’s what a Clachanach farmhand once said, no doubt after picking pebbles from underneath the blade of his plough all day: “It wasn’t a nickname they gave this place!”

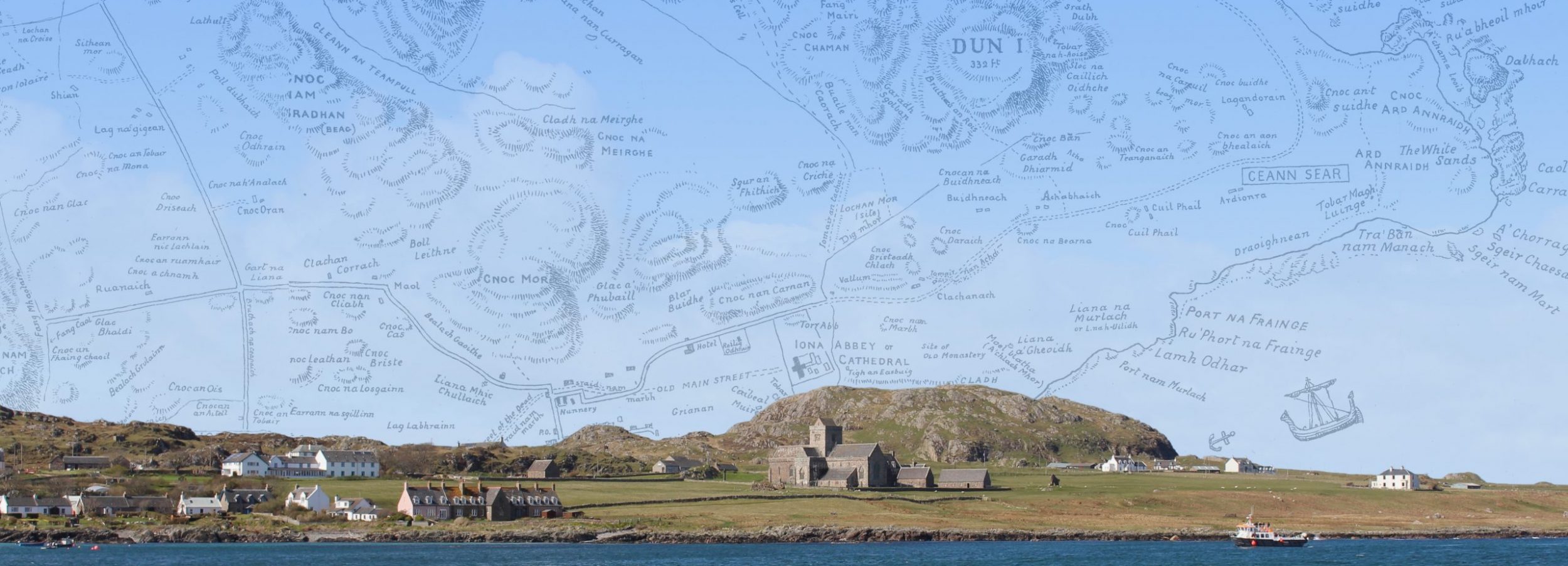

The meaning given for ‘Clachanach’ in the 1928 Ritchie map appendix is simply ‘place of stones’. It is a croft, around 200 metres north of the Cathedral and tenanted by generations of a MacArthur family since 1802. That was when people began to move from the village on Iona’s east side to take up individual holdings allocated by their landlord, the Duke of Argyll. They built houses, steadings, walls and, in due course, they gave their places names.

We don’t yet know how much of the outlying land was already named before this new crofting era began. On his 1769 estate map, William Douglas delineated the portions of pasture, meadow and arable then held in common but he included no specific field-names. In 1762, however, he had been asked by the Duke to measure out a section of arable, as a glebe for the minister, and instructions in the Mull Presbytery minutes state the following: one boundary to be the stone dyke which divided the Cathedral grounds from ‘the field called Clachanach’ to the north. Thus the croft’s first MacArthur tenant chose what was an existing and neighbouring field-name – the only documentary record of this kind we have found so far.

Stones of all kinds, below or above the surface, are linked to Clachanach. In the early 20th century my grandfather found a whetstone in the Losaid, a word that means ‘kneading-trough’ and is the name for a field east of the house, good for growing potatoes. He sent the stone to what was then the Museum of Antiquities in Edinburgh. Cnoc Bristeadh Chlach, ‘hill of stone breaking’, lies immediately behind the house and close by the north corner of the vallum. Tucked into the east-facing side of the latter was the cottage of another crofting family, Camerons, who emigrated to Australia in the 1830s. As their old home decayed, their Clachanach neighbour took down the walls in case they tumbled onto his children, for whom the ruin had become a playground. Besides, spare building material was always useful in an island mostly bereft of trees.

So, was Cnoc Bristeadh Chlach a place where stonework was regularly broken up? Or had the hillock’s own rock been quarried for domestic or creative purposes over the centuries? The historian W.F. Skene, who took a keen interest in Iona over many years, noted that ‘fragments of a cross’ were said to have been found ‘behind the barn’ at Clachanach. [Celtic Scotland, 2, 98-99]

In the 1950s and ’60s, relays of cousins spent part of July and August on holiday at Clachanach. Our grandmother and aunt fed us three meals a day and packed picnics for outings. The nearest of these was to Port an Diseirt, ‘hermitage-port’, on a shoreline of gullies fringed with pink sea-thrift, rock-pools and a sheltered, sandy cove. This spot became such a favourite that the island cousins named it ‘Aunt Eilidh’s Bay’ after one of the aunties who often led a troop of children towards the sea. On the way we passed the old well and a low stone wall across the field. Unknown to us then, masons long ago will have handled those stones which came from rubble cleared during restoration work to the Cathedral between 1902-1910.

We did however know all about two particular stones, linked by a family story. The first was a huge mass of pink granite, A’Chlach Mhòr, ‘the big stone’, dominating the fields between house and shore. In the text of Ritchie’s book, Iona A Map, he referred to this as ‘a relic of the ice age and called St Columba’s Table.’ The second stone was a mere 48 x 40cm in size, housed in a metal cage in the abbey museum and labelled, in English only, ‘St Columba’s Pillow’. Dugald MacArthur, my great-grandfather, used to gather seaweed at Port an Diseirt, transporting it to his fields by horse and cart. About 100 metres from the shore he would pass the grassy, rectangular enclosure named Cladh an Diseirt, ‘burial-ground of the hermitage’. A wheel jolted so often at the same place that one day he dug out the obstacle – an oval boulder, carved on one side with a plain ringed cross. He laid it on top of A’ Chlach Mhòr and informed the Church of Scotland minister, the Revd Alexander MacGregor, who arranged for it to be kept under cover in the Cathedral precincts. This all happened around 1870.

More than a century later, Dugald’s grandson and namesake took a photograph at Cladh an Diseirt, with the handle of his walking stick laid at the exact spot where he had been told the stone was found (see image). The photo looks west, away from the sea: on the left are two of the large stones that once formed a gateway into the site; on the skyline are the houses and barn-roofs of the 20th century Clachanach croft.

There is, however, an alternative name and a different story. In 1857 William Reeves recorded Cladh Iain, ‘graveyard of John’ in his list of Iona place-names although his map used only Cladh an Diseirt along with the word Leachd. That can mean ‘flagstone’ or ‘tomb’ but he did not identify what stone was meant. Thomas Clancy’s Ì Chaluim Chille blog of 9th June has two links relevant here: one to the Canmore image of the oval stone and another to an account by artist James Drummond, in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (1870-72), where he put forward the idea that this might be the stone ‘pillow’ on which, according to Adomnán, Columba laid his head. He also relayed a letter from the Iona minister’s nephew, who claimed that he had been the first to find the stone, in a field drain, and that he had carried it to Cladh an Diseirt where it more properly belonged. It is not impossible that this happened and, by the time Dugald’s cart passed by, the stone had sunk into the turf – although why young MacGregor did not inform his uncle of the find is unclear. The common thread in both tales is that a wheel must have broken off a small piece from the top of the stone.

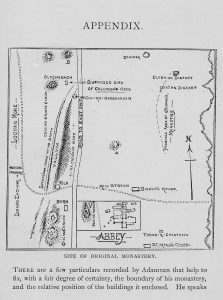

Drummond speculated further that this stone might also have marked the Saint’s grave. And, if the Saint was buried at Cladh an Diseirt, then perhaps the whole Columban monastery had lain farther north than the site of the later Benedictine Abbey. The giant stone might have served as a communion table, or been part of the refectory. These ideas greatly intrigued the wider antiquarian community, including Drummond’s colleague W.F. Skene and the interest was infectious. In his 1898 book on Iona’s history, the island’s minister Archibald MacMillan (brother-in-law to Alec Ritchie) made the same case in a special Appendix, complete with a plan of the area between the vallum and Cladh an Diseirt. Traveller and writer M.E.M. Donaldson drew her own monastic layout in the Iona chapter of Wanderings in the Western Highlands and Islands [Paisley, 1923, 2nd edn, p.350]. On both maps the site of Columba’s cell is more or less where the Clachanach house stands. And there was further excitement in 1905 when, during excavation for an extension south of the house, the skeleton of a horse was found. It lay seven feet down, oriented east-west and carefully covered by rough granite blocks. Could this have been the white horse blessed by Columba on the evening before the saint died? A visitor offered to take two teeth to be examined by a vet in Oban, whose cautious verdict was that ‘they belonged to a very aged pony.’

In 1866 Drummond had drawn the imposing entrance to Cladh an Diseirt: two large pillars surmounted by a third. In his watercolour of 1874, looking south across to the tower and unroofed choir of the Cathedral, the top stone is no longer there. Again there are two stories. The more common is that the crofter pulled down the stone, lest it fall and harm livestock. The other centres on a couple of boatmen from Mull, who were waiting for parishioners they had brought over from Deargphort to attend church in Iona. Bored, perhaps, or attempting some feat of strength, they felled the slab of stone. Incidentally, this confirms a remark by Mull writer John MacCormick that Deargphort to Port an Diseirt was an old ferry route between the two islands.

The name ‘St Columba’s Table’ did not last long in local usage but A’ Chlach Mhòr most certainly did. It has long been a familiar part of Clachanach’s crofting landscape and an impressive landmark in any season, surrounded by spring crops, summer haystacks or grazing livestock. ‘St Columba’s Pillow’ is still displayed in a cage in the Abbey museum, but now with the lid open. Alec Ritchie used the oval shape, and the name, to design a silver pendant, sometimes setting the cross onto a background as blue as the Sound of Iona. Contemporary silversmiths, with a direct link to the Ritchie heritage, ensure its continuing popularity. For example, Aosdana Gallery on Iona produces a silver ‘pillow’ charm and The Iona Shop in Oban sells an enamelled oval pendant.

But the most unusual, and moving, item I know of is a tiny amulet, carved out of white stone with Black Watch and the date 1915 around the cross and, on the other side, the words ‘St Columba’s Pillow’. It was spotted by chance in an Oban rock-pool 30 years ago and thanks are due to the finder, David Brooks, for getting in touch and sending the photos. A soldier from WW1 may have carried this lucky charm into conflict – in his pocket or sporran or, as was common practice, sewn into his cap or jacket. I would like to hope that the survival of the charm means that he too came home safely from the War.