In our blog for September, Sofia Evemalm-Graham reflected on some of the names attached to the hill called Sìthean Mòr.[1] She looked mostly at various more modern names for the hill and some associated story-telling, but this month I want to look a little further back, exploring medieval references to the hill, and some aspects of the place and its landscape situation. I will refer to the hill in this blog by the Gaelic name that Adomnán gave it in the seventh century, Cnoc Angel, ‘hill of [the] angels’. I do so simply so that we can remind ourselves that this name comes to us from his pen, and reflects his mental map of the island; I am not suggesting that it be used as a modern form.

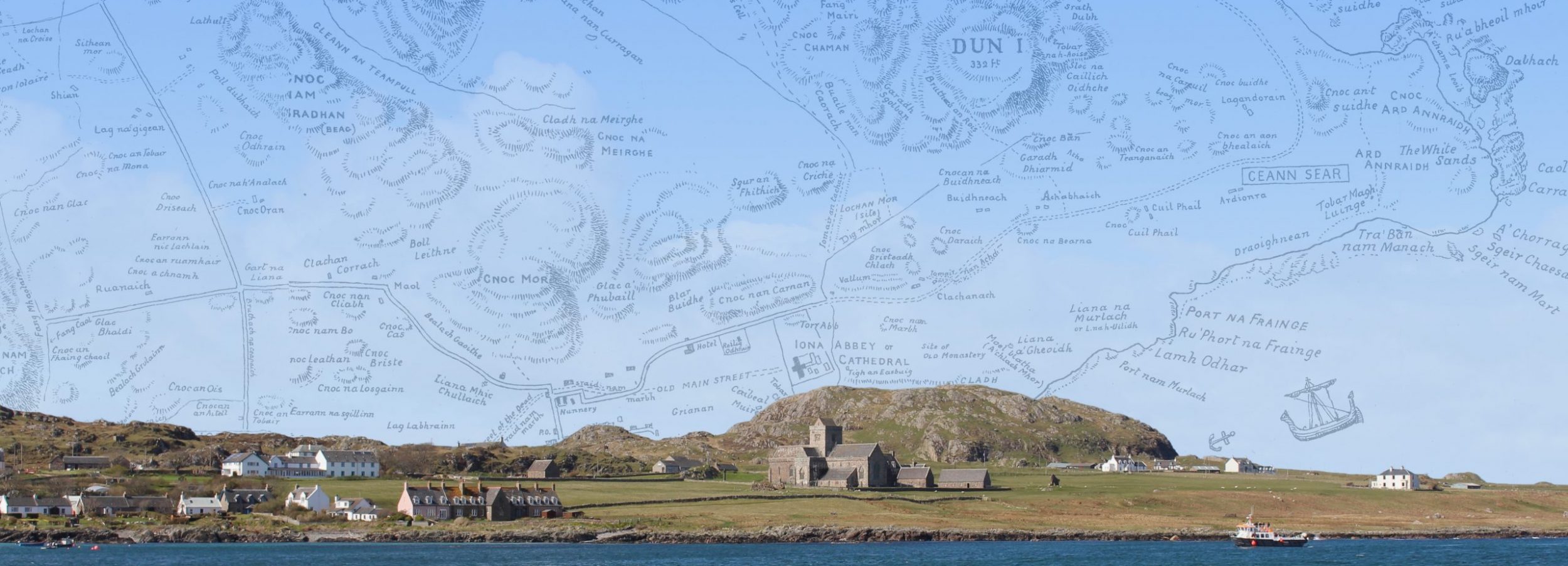

Cnoc Angel from the north-west

(photo: Gilbert Márkus)

As Sofia pointed out, this hill first appears to us in a pair of stories in Adomnán’s Life of Columba. Let’s refresh our memory. The first story explains how the hill got its name, recounting how the saint went out to the western plain (in occidentalem … campulum), the Machair, while one of his monks secretly climbed a hill overlooking the plain to spy on him. From his vantage point the naughty monk saw the saint on a knoll, ‘praying with his hands outstretched to the sky’, and then:

Strange to tell, behold suddenly a marvellous thing appeared …. holy angels, citizens of the heavenly country, flew down with marvellous suddenness, clothed in white raiment, and began to stand about the holy man as he prayed. And after some converse with the blessed man, that heavenly throng, as though perceiving that they were watched, quickly returned to the highest heaven. … And hence even today the place of that angelic conference bears witness to the event, in its proper name, which may be rendered in Latin ‘knoll of the angels’ (colliculus angelorum), and in Gaelic cnoc angel.[2]

This story establishes the importance of the site in Adomnán’s imagination, and in the imagination of the monks of Iona. It was what they might have called a ‘holy place’, a place which some event of the past had established as a place of encounter with the divine, a place of blessing.[3] We might also note that what Columba does is very much like a cleric performing a liturgy. He stands with his hands raised (in what liturgists call the orans or ‘praying’ position) while surrounded by a congregation – a congregation of angels – who ‘stand around’ him (circumstare) as if he were the celebrant at an event in a church. This place is not only a holy place, therefore, but the site of a liturgical action. This liturgical and ritual aspect of Cnoc Angel reappears in another story told by Adomnán.

About seventeen years ago, in the season of spring, there was a very great drought, persistent and severe, in these lifeless fields … We formed a plan, and decided upon this course: that some of our elders would go round the plain (campum) that had lately been ploughed and sown, taking with them the white tunic of Saint Columba, and books in his own handwriting; and should three times raise and shake in the air that tunic, which he wore in the hour of his departure from the flesh; and should open his books and read from them on the hill of the angels (in colliculo angelorum), where at one time the citizens of the heavenly country were seen descending to confer with the holy man.[4]

Naturally, it started to rain very shortly afterwards. This time it is not Columba who conducts the liturgical action on the hill, but his monks, including Adomnán himself, a hundred years later – probably in the 680s. The angelic liturgical site established by Columba has become a monastic liturgical site by the seventh century, with a ritual reading from Columba’s books. The monks of Adomnán’s time have incorporated this hill into what is a monumental and sacral landscape. It may not be coincidental that Cnoc Angel appears to be close to the place which Adomnán calls Cuul Eilne, where Columba sends his spirit to meet and comfort his exhausted monks as they are returning from the machair to the monastery – probably somewhere on the road below, or just east of, Cnoc Angel. Cuul Eilne seems in Adomnán’s ‘mental map’ to mark a boundary between the arable western plain and the more strictly monastic east side. The machair also seems to have been where there was a hospitium or guest-house for visitors to the island, at some distance from the monastic enclosure.[5]

On this stretch of road is likely to be Adomnán’s Cuul Eilne.

Cnoc Angel is the little hill in the background.

(Photo: Gilbert Márkus)

In the mid-sixteenth century this hill of the angels appears once again in the records of Iona. In 1549, Roderick MacLean, bishop elect of the Isles, was in Rome (probably seeking papal confirmation of his election to the see). While he was there he published a long poem in Latin, a versification of parts of Adomnán’s Life of Columba.[6] His poem includes the story of the drought and the rain-making ritual on Angels’ Hill. But it also includes a reference to another wonderful place on Iona: the bay where Columba’s boat was thought to have landed when he sailed from Ireland. Clearly it was already a ‘holy place’ by 1549. MacLean knew Iona well, having been to school there as a boy, and then having been Archdeacon of the Isles for some years in his adulthood. He must have been familiar not only with the physical landscape, but with any rituals that took place there. One verse of his poem refers to the bay where Columba landed his boat, and records that cairns were erected ‘as momuments of Christ to future ages’. This is the bay now called Port a’ Churaich (‘bay of the currach’). Adomnán makes no mention of this bay, and gives no indication of where on the island he thought Columba had landed. But it was clearly a feature of the cult of the saint by the eve of the Reformation when MacLean was writing, and it continues to appear in the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century accounts of the island. It is still a place of local pilgrimage today. To get there from the abbey the natural route is to go south along the shore road, across the island to Cnoc Angel, and then south again through the hills to the bay. Cnoc Angel is therefore a ‘turning point’ or a ‘ritual moment’ in the later medieval pilgrim’s landscape.

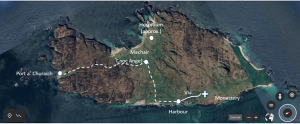

Adomnán’s Iona, plus Port a’ Churaich

Adomnán’s Iona, plus Port a’ Churaich

Satellite Image from Google Earth

(North is to the right – see compass in the corner)

Cnoc Angel lies at the centre of this landscape of movement around the holy places and the interconnecting routes. It is worth noting, incidentally, that the ritually significant sites are concentrated on the green ground on this satellite photo, avoiding the rugged terrain – apart from Port a’ Churaich.

There is something else that suggests that Cnoc Angel remained a centre of cultic activity long after Adomnán and his brethren did their rain-making ritual there. Richard Pococke, bishop of Meath in Ireland, visited Iona in 1760. He wrote an account of his visit:

I went to the South west part of the Island in half a mile passed by a fine small green hill, called Angel Hill, where they bring their Horses on the day of St. Michael and All Angels, and run races round it; it is probable this custom took its rise from bringing the Cattle at that season to be blessed, as they do now at Rome on a certain day of the year.[7]

Evidently the celebration of the angels on the Angel Hill was still a going concern, though there is little reason to accept Pococke’s explanation of the ceremony as a cattle-blessing event. Even more interesting is an account from 1773, a letter of John Stuart to Thomas Pennant which describes his visit to Iona and mentions our little hill: ‘There are hardly any monuments of Druids now remaining in this island, excepting a Druidical circle, 15 feet in diameter, which is to be seen on the top of Cnoc-nan-aingeal.’[8] The previous year, Pennant had been here himself and observed:

On my return [from Port a’ Churaich] saw, on the right hand, on a small hill, a small circle of stones, and a little cairn in the middle, evidently druidical, but called the hill of the angels, Cnoc nar-aimgeal (sic); from a tradition that the holy man had there a conference with those celestial beings soon after his arrival. Bishop Pocock informed me, that the natives were accustomed to bring their horses to this circle at the feast of St Michael, and to course round it. I conjecture that this usage originated from the custom of blessing the horses in the days of superstition, when the priest and the holy water pot were called in: but in latter times the horses are still assembled, but the reason forgotten.[9]

Though there is broad agreement in the two accounts by these two men who were corresponding with each other at the time, the descriptions of the monument on top of the hill seem to be based on first-hand experience. Both of them seem to have actually seen Cnoc Angel and observed some kind of archaeological object on it, of which nothing now remains to be seen.[10] Stuart saw ‘a Druidical circle, 15 feet in diameter, which is to be seen on the top of Cnoc-nan-aingeal’, while Pennant saw ‘a small circle of stones, and a little cairn in the middle, evidently druidical’.

A few years later, in 1788, Lord Mountstewart visited Iona, and recorded the monument on Cnoc Angel as ‘formerly a sacred spot, and the ruins of a chapel are still to be seen’.[11]

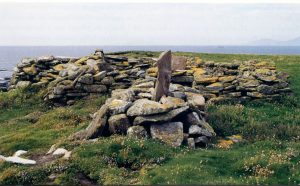

Clearly there was something on Cnoc Angel which appeared to be a built structure. The interpretations of the three witnesses differ rather dramatically in terms of what they thought they were looking at (a ‘Druidical circle’ or a ‘chapel’), but this may have been simply because they were unfamiliar with such monuments. But we know of structures on other early medieval monastic sites which were part of the ritual process of movement around the landscape, and which may explain the feature here on Iona. On Inishmurray, for example, are a number of leachta. Some of them are much reduced, their stones scattered in a way that makes them hard to interpret (perhaps something like what Pennant, Stuart and Mountstewart saw in the eighteenth century), while others are more intact.

Trahanareear, Inishmurray: one of the leachta, with small enclosure behind.

Trahanareear, Inishmurray: one of the leachta, with small enclosure behind.

(photo reproduced with kind permission of www.inishmurray.com)

The word leacht derives from Latin lectus ‘a bed’, and therefore ‘grave, tomb, resting place’. In Irish Gaelic it refers to a class of monuments which play a prominent role in ritual activity around ‘holy places’. In spite of the origin of the word, not every leacht actually marks a burial. The word is used of the kind of marker for ritual movement that we see on Inishmurray, where there is a whole series of leachta around the coast of the island which were mostly not grave-markers but served as points in the pilgrims’ ritual perambulation of the island. The report on the excavations of these leachta on Inishmurray suggest that they were erected between the ninth and eleventh century, and that they may have served at some times as altars as part of this ritual movement.[12]

Another Old Gaelic word for such monuments marking ritual movement is ailad. This word appears in an extraordinary range of spellings (aulad, ilad, elad, ulad, ilaidh, ula, ila, eala and more).[13] It originally meant ‘a burial-place or tomb’, but subsequently was also used monuments which served as ritual markers in a pilgrimage or ‘penitential stations’ on such a route. One of the leachta on Inishmurray is actually called Ollamurray, or Ulaidh Mhuire ‘Mary’s ailad’,[14] and the word also appears in the Iona place-name An Eala, the name of a monument which formerly attracted various rituals and on which bodies were rested briefly having been landed at Martyrs’ Bay, before being carried to the cemetery for burial.

It might be objected that, unlike the stones seen on Cnoc Angel, leachta are not typically on top of mounds, but the fact that our monument was on a small hill should not prevent us from seeing it as part of this class of monuments. The authority of Cnoc Angel’s past (Columba and the angels, Adomnán and the rain-making ritual) together with its role in later ritual activity would surely be sufficient to warrant the construction and use of a leacht on its summit. It may also be significant that the top of Cnoc Angel offers long views across the island, and out to sea in the west, and all the leachta on Inishmurray (apart from the three within the actual cashel) likewise offer long views across the sea. Could this also be part of the attraction of the site? It would be a worthwhile piece of research to discover whether other leachta elsewhere had similarly long sight-lines.

There is one final final hint of support for the above suggestion. Leachta are often marked out as ritual sites by a carved cross-slab erected on top of them, like the one in the picture above (and most of the others on Inishmurray). Many years ago such a cross-slab was found in a farm building on Sithean farm, very close to Cnoc Angel. It is some distance from the monastery, where most (or all?) of the other early medieval crosses were found. I suppose it is possible that it was taken from the monastery and brought to Sithean to be used as a building stone, but that seems unlikely. More likely is that it was originally installed locally.

The cross-slab bears a worn and partly effaced inscription whose surviving legible part reads oroit, ‘a prayer’. In monuments like this oroit is typically followed by do and a personal name: ‘a prayer for [the soul of] so-and-so’.[15] Clearly it was originally a memorial to a dead person, probably a recumbent stone marking their grave. Does that mean that there was a burial ground in the vicinity? There is actually some support for this idea. About 130 metres west of Cnoc Angel, during a watching brief at the site being prepared for the building of a house (now built and called Skerryvore), Clare Ellis of Argyll Archaeology found ‘two sub-rectangular pits, both of which were filled with brown sand’, looking remarkably like a pair of graves.[16] It may be that the ‘holy place’ of Cnoc Angel was monumentalised not only by a leacht, but also by a burial ground. In that case the cross-carved stone is quite likely to have come from the burial ground itself. It is possible, however, if O’Sullivan and Ó Carragáin are right in dating the leachta on Inishmurray to the ninth-to-eleventh centuries, that the proposed Cnoc Angel leacht was also erected during this period, and one possible scenario is that a cross which was initially made as a recumbent funerary monument (either here or at the monastery) was later recycled by being erected upright on top of a leacht.[17]

Perhaps it’s time for some archaeology to be done here, to see if anything remains of an early leacht or other ritual monument marking this nodal point in the ritual landscape.[18]

[1] Thus, without accents, on the map published by the Iona Community (Wild Goose Publications, 2017). It has other names as well: Cnoc an t-Sidhein on modern OS maps, Cnoc an t-Sìthein on OS 1st edn.

[2] Alan Orr Anderson and Marjorie Ogilvie Anderson (eds), Adomnán’s Life of Columba (Oxford 1991) [hereafter VC]. iii, 16. I will use the spelling of the name which Adomnán used in this blog. Other Gaelic sources call it Cnoc nan Aingeal vel sim.

[3] Adomnán had already written one book by this time ‘on the holy places’ (De locis sanctis) which discussed the spiritual authority of places in the Mediterranean world, particularly places associated with Christ and his saints; his second book, the Life of Columba, can in some ways be seen as a treatise on the ‘holy places’ in Iona and the surrounding area, associated with his patron saint. For the (slightly problematic) notion of a holy place in the early church, see R. A. Markus, ‘How on Earth could places become holy? Origins of the Christian idea of Holy Places’, Journal of Early Christian Studies 2:3 (1994), 257-271.

[4] VC ii, 44.

[5] VC i, 37. The hospitium appears in VC i, 48. See Gilbert Márkus, ‘Four blessings and a funeral: Adomnán’s theological map of Iona’, The Innes Review 72 (2021), 1-26, 12-14.

[6] Dr Alan Macquarrie is currently preparing an edition and translation of this poem, to be published by the Scottish History Society next year. I am grateful to him for letting me see a pre-publication copy of some of his work.

[7][7] Richard Pococke, Tours in Scotland (Edinburgh, 1887), 86.

[8] The letter and its enclosure are edited and published here: https://editions.curioustravellers.ac.uk/doc/0428.

[9] Pennant, 297

[10] I visited the site in September 2021.

[11] National Library of Scotland, MS 9587.

[12] Jerry O’Sullivan and Tomás Ó Carragáin, Inishmurray: Monks and Pilgrims in an Atlantic Landscape (Cork 2008), 7 (map showing leachta), 319-26.

[13] Dictionary of the Irish Language, see dil.ie/961.

[14] Interestingly, the small leacht or ailaid of Ollamurray is also surrounded by a stone enclosure, roughly 6m square. Might such an arrangement be what Pennant saw as ‘a small circle of stones and a little cairn in the middle’? O’Sullivan and Ó Carragáin 2008, 169-72.

[15] For other examples of stones inscribed with this formula see RCAHMS Argyll, an inventory of the monuments: Volume 4: Iona (Edinburgh 1982), 181, 185, 186.

[16] ‘Sithean House’, in Discovery and Excavation in Scotland 12 2011), 43. For a more detailed report see also Argyll Archaeology report 137, ‘Watching Brief and Controlled Topsoil Strip, Sithean, Iona, Argyll’. Note that the grid reference for the site given in both these reports is mistaken. It should be NM2708.2371.

[17] Given that leacht originally meant ‘burial’, might the monument on Cnoc Angel have been (or been seen as) the burial place of the person whose name originally appeared inscribed on the cross?

[18][18] I am grateful to Sofia Evemalm-Graham, Thomas Owen Clancy and Katherine Forsyth for comments on an earlier draft of this blog.