Visitors have long enjoyed exploring Iona by themselves, both on and off the beaten track. Today’s islanders also offer excellent guided tours, for example on foot with Iona Trails or, for a view from the sea, with Alternative Boat Hire. Here Mairi MacArthur describes a few pathways remembered in family and local history:

An Rathad a Ghabh e Fhéin

The Road he Took Himself

The MacGillivray family who moved from Mull to Iona in the mid-1860s, and settled on the croft named Cnoc Oran in the west end of the island, were known as Na Dròbhairean – The Drovers. Over several generations, they had taken part in the annual gathering of cattle, to be swum and driven across to the Argyll mainland and on south to the markets of Crieff or Falkirk. Duncan MacGillivray, born in 1877, was known to be a man with an instinct for a direct route. If he wanted to meet a boat at the jetty, or go to the village street, he paid no heed to roads or gates. He would simply jump the wall enclosing the Sligineach crofts and tramp diagonally north-east, through meadow or crops, to reach his destination.

When he died in 1952 the island men gathered at the house, as was customary, to help convey the coffin by horse and cart to the Reilig Orain. The horse was skittish, as could happen at funerals – perhaps because the men were in dark jackets, rather than their normal work clothes, or because there were more people around the animal than usual. During the delay to calm the animal, an argument broke out. Should they risk taking the shorter, but steep and stony, slope past Maol farmhouse, down to the Nunnery corner and join the road there? Or should they go by the more even, but longer, route to the Sligineach shore and along past Port nam Martair? Eventually, someone’s patience wore thin: ‘Ach, carson nach gabh sibh an rathad a ghabh e fhéin ? why not take him the road he took himself? through the crofts!’ The stalemate was broken. And, although my father’s memory did not include by which road the nervous horse was eventually led, that key phrase remains resonant: ‘the road he took himself’.

People living everywhere, in city or countryside, find shortcuts if they want them. At first glance, Iona might seem too small for this to be necessary. The modern road links inhabited houses from north to south perfectly well. But what of the times before much, or any, motorised transport? I recall childhood holidays in the 1950s, when my father walked us to Culbhuirg to visit the MacInnes family. We started on the road south from Clachanach to the St Columba Hotel but then cut up into the hilly area behind the Parish Church, where we followed the old stone wall that divides East End from West End to reach the head of Gleann Cùl Bhuirg. From there it was a short trek down the glen to the house.

When my father was a boy, he regularly took a shortcut behind Achabhaich house and around the foot of Dùn Ì’s north side, in order to reach Calva where his father had tenancy of the crofting land. Another route was around the Lochan Mòr behind Clachanach house, up onto the hummocky ground below Dùn Ì and down onto the grassland and rocky coast of Calva. The last time he and I did this, he was keen to find a strangely marked stone which he had not seen for years. Amazingly, we did find it, sunk into grass close to Fang Mairi, a green enclosure named for a long-forgotten ‘Mary’. The holes and hollows on the stone could be natural or perhaps manmade, as one or two seem to resemble animal hoof prints. Emily Wilkins, the National Trust for Scotland ranger, tells me that there is a similarly ‘carved’ stone close to Burg Farm on the Ardmeanach peninsula on the Ross of Mull, although that one is not thought to be of any great age.

It is not clear when the stone west of Clachanach became known, but might it have acted as a marker for this particular route over the hill ground? A tragic event from the 19th century illustrates how well even the young islanders got to know their own locality. An infectious disease was rife at the time and the MacArthurs at Clachanach decided to send their youngest boy to a relative who lived at Calva, as that was the most isolated household in their part of the island. But the lad was homesick and made his own way back over the hill. He did reach home but was cold from the wet ground underfoot. This brought on a fever and he died a few days later.

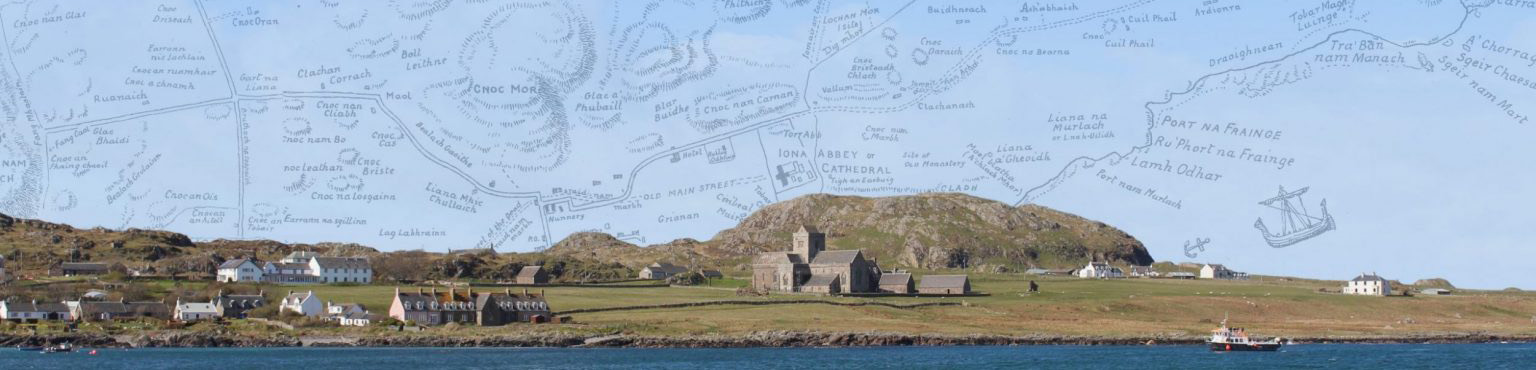

The sea routes brought people, goods and livestock which all needed to be matched by land tracks. Port Rònain, from which the island roads fan out, has become the best known landing-place although it was not the only one. In my blog ‘Stones and Stories’ in August 2021, I cite a remark by Mull writer John MacCormick that Deargphort to Port an Dìseirt was an old ferry route between the Ross and Iona. Also, in those sailing days, if wind or tide made the usual landing at Port Rònain difficult, the ferryman would head farther north to put his passengers ashore at Port na Fraing. Informal pathways will therefore have evolved along the north-east coast to the village area. In the early 1800s, of course, when the former huddle of scattered cottages was gradually replaced by a straight line of houses facing the sea, a path from one end of the village to the other became part of that new arrangement.

Travel was also in the other direction, for example when islanders crossed to Mull from Iona to dig peat, after their own small supply had been depleted. And they left at least two place-names on the landscape. Cnocan Beag nan Ràmh, ‘Hillock of the Oars’, lies at the junction of the main road just outside Fionnphort and the smaller road towards Kentra. The Iona folk left their oars there before walking on to the peat banks at Creich allocated to them by the Duke of Argyll. And that track became known locally as Rathad Mòr Mhuinntir Idhe, ‘The Big Road of the Iona People’. The word ‘road’ appears in only two place-names on Iona itself, one in English and one in Gaelic. Close to where the MacGillivrays lived in the West End, two ways intersect to form what, in many places, would be called a ‘cross-roads’ but the local Iona n

ame is ‘The Four Roads’ – always in English. I have never heard nor read a Gaelic version. ‘Four Roads’ occurs elsewhere as a place-name, for example it is the name of a village in County Roscommon in Ireland. But when, and by whom, the term was coined on Iona is not clear. The name does not appear on any maps of the island and so visitors would only get to know it from local people. Some travel accounts, for example by M.E.M.Donaldson in 1920 and Ellen Murray in 1935, simply refer to ‘the cross-roads’.

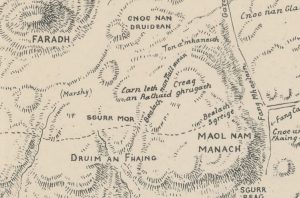

Close to one of the four spurs, leading south towards Druim Dhùghaill, is a spot whose name used to baffle me: Càrn Leth an Rathaid (Grid reference: NM274229) – a cairn of the half road? But what road and where to? Then, in conversation with Calum Cameron of Traighmòr, but with no prompting by me, he mentioned that there used to be a cairn above Ruanaich which, according to his father, marked the half-way point between the village and the farthest rig which the islanders had to plough and sow. This explanation is entirely possible and takes us straight back to the pre-crofting era before 1802, when most of the population lived around Port Rònain and Port nam Martair, but were allocated strips of arable ground across the island by the landlord, in the system known as run-rig. The stones that formed this cairn will have long since tumbled into the heather but, in its day, it was clearly a useful landmark. I like to imagine people walking to and fro, stopping there to rest and to talk – exchanging news, predicting the weather, discussing the crops and maybe reflecting on how Druim Dhùghaill got its name. But that is another story.