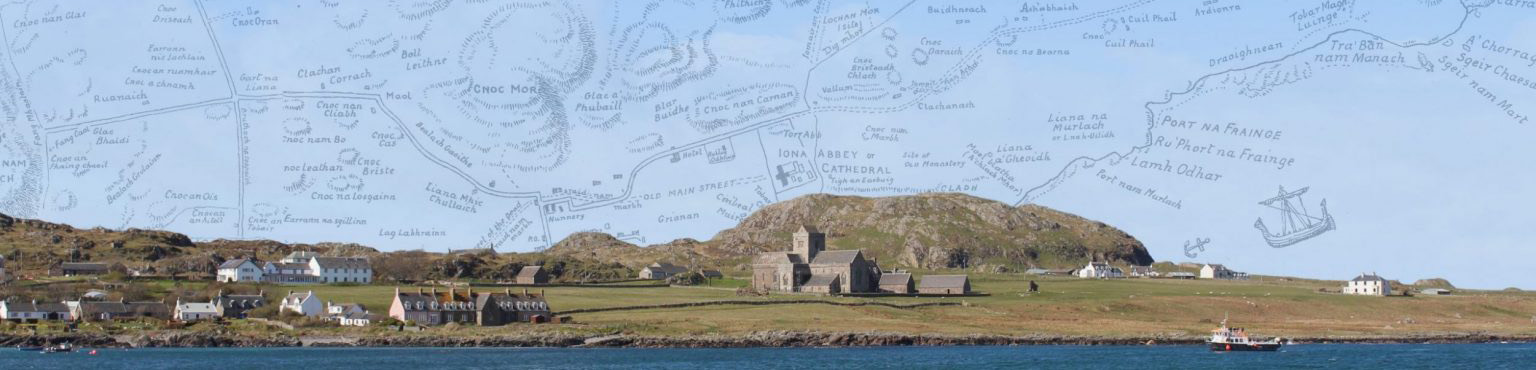

Mairi MacArthur looks at two place-names – one on land, one at sea – and wonders if, and how, they may be related.

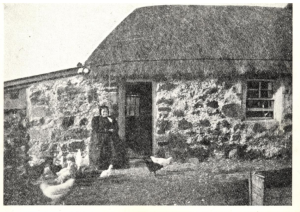

Our December Name of the Month featured Brown’s Rock on which a schooner, The Guy Mannering, foundered on the last day of 1865. Seven islanders were recognised by the Royal Humane Society for their bravery in rescuing crew and passengers. John Campbell, awarded a bronze medal, lived closer than anyone to the scene of the tragedy. Then in his 30s, he was the shepherd for the West End grazings and lived above the shore at the southern end of the Machair, in a house named Culdamh. (NM 26827 23342)

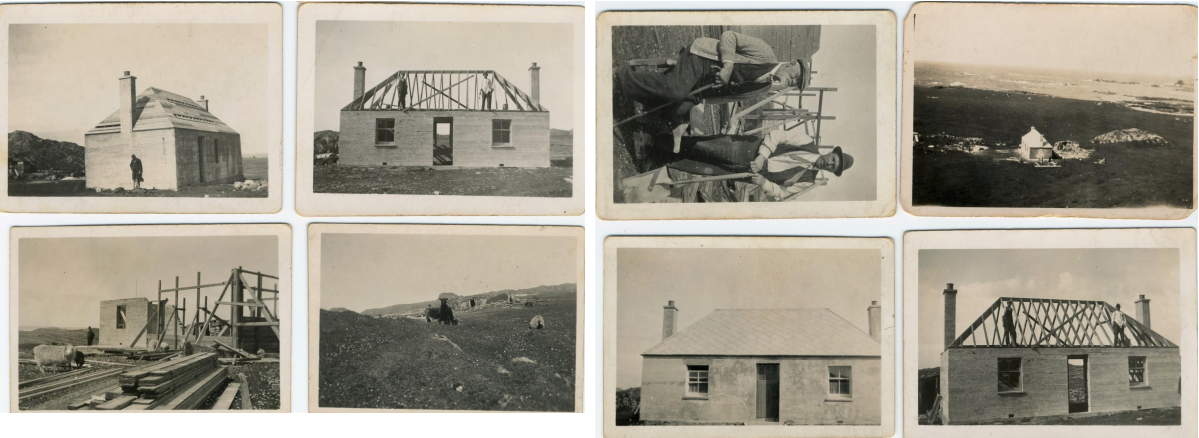

This was one of 30 crofts created around 1802, to provide tenants with individual holdings. In 1836 Iona’s parish minister recorded the name of Malcolm MacInnes, crofter at ‘Cultaimph’ when registering the marriages of two offspring. He was the first tenant but left the island in the 1840s. In 1851 a baptism was registered at ‘Cultaimph’ for Colin Cameron, whose father then held a half-share in the croft along with Colin Campbell, who had moved from nearby Culbhuirg around 1847. The Camerons emigrated a few years later but the Campbells stayed and the house has remained in that family’s hands to this day. The Census for 1851 gave the name as ‘Cultaimh’ and from 1861-1911 as ‘Culdamph’. The 1881 and 1900 OS 6 inch maps spelled the name ‘Culdamh’, which is the form now used on the island.

I had long assumed that the first tenants of Culdamh followed the local practice of naming their holding after a nearby land or coastal feature – in this case the broad stretch of water in full view of the house, recorded in the 1928 Ritchie map Appendix as: ‘Camus Cul an taibh. The bay at the back of the ocean,…’ Gaelic ‘cùl’ means ‘the back of something’ and ‘taibh’ in the nominative is ‘tabh’, thought to derive from the Norse ‘haf’ for ‘open sea’. So this entry appears to give us a perfect translation. But there is more. After ‘ocean,’ D.Munro Fraser added ‘…or ?Cuildamh bay.’ The question mark implies an alternative interpretation: that the bay was named after the croft house, and not the other way around.

Also in the 1928 Appendix, D.Munro Fraser gave ‘Cuil-damh. Ox-shelter or -nook’ for the name of the house, taking the first part to be not ‘cùl’ but ‘cùil’ which is a different word meaning ‘nook or corner or recess’. The mention of ‘ox’ brings to mind another spot on Iona’s north-west coast: ‘Carraig an daimh. Rock of the ox’, where a large stony outcrop does resemble a hefty animal. Could today’s Culdamh have started out as ‘Cùil an Daimh’, after some large shape in the hillocks behind the house? But we know that the word ‘cùil’ was in use on the island for other place-names, with the sense of ‘nook or recess’. So a simpler explanation is more likely, given the agricultural importance of the Machair plain over many centuries: a corner of the rocks might well have served as a stall for oxen, ideal beasts for ploughing and drawing heavy loads. This meaning raises yet another question. Was ‘Cuil-damh’ already a field name, in use before the crofts were created? The area is clearly marked as ‘arable’ on the estate map drawn by William Douglas in 1769. And we know of another example: the field name ‘Clachanach’, found on a 1762 document and subsequently used for the nearest croft. (See blog ‘Stones and Stories’, August 2021).

So, turning again to the bay, more tangles emerge as to where and when this was named, or not named, in print. In Antiquities of Iona, published in 1850, Henry D. Graham drew a supremely simple map: the island’s outline plus a few nearby islets and he annotated the sketch with a scant 30 place-names. One of those he listed as ‘Cul Taimh (the Back of the Ocean)–a farm shut in by the hills and sea.’ The farm was correctly placed. But for the sea, bordering it on one side, Graham noted no name at all. From 1848-1854 he lodged in the Free Church Manse, as guest of the Revd Donald McVean and family. McVean had good local knowledge of the island’s history and topography, which he also shared with scholar Dr William Reeves of Dublin whose edition of Adomnan’s Life of Columba was published in 1857. This had a much more detailed map of Iona plus a list of place-names which included, clearly sited on the south-west corner of the Machair, ‘Cultaimh’ and, along the shore-line, a string of named ports, coves and skerries. But again the big bay itself was not named.

However, the first Admiralty Chart for the Sound of Iona was surveyed in 1859. This did the opposite of Reeves: it named none of the small ports along the Machair rim but, out on the water, gave two names: ‘Camus chuil ant Saimh’ and, just north of that, ‘Bogha ant Saimh’ – a bay and a reef both described as ‘of the ocean’. The reef name recurred on chart revisions up until 1933 but disappeared from 1957 onward. Up until that date also, charts recorded ‘Cultaimh’ on the south end of the Machair. On the 1957 version is the note: ‘The topography is taken generally from the Ordnance Survey’. On early charts the surveyors’ names are given but one wonders who they talked to and just how they gathered local information about the myriad inlets and islands, channels and coves all around our seaboard.

Today, ‘The Bay at the Back of the Ocean’ is a widely used English name for the Machair’s broad curve of sand, rock and surf. When it became so popular is harder to pinpoint: the official report of the 1865 shipwreck noted that the captain chose to run the vessel into ‘Machair Bay’; Ellen Murray, in her book Peace and Adventure in 1935, referred to ‘the Camus (Shore)’. The name does not appear at all in the copious antiquarian literature from the 18th to the early 20th centuries, but it has become very common in more recent descriptive or meditative writing about Iona. People like the idea that this great bite out of Iona’s western side lies at the end of a sea stretching from the shores of Labrador. ‘The Bay at the Back of the Ocean’ is an evocative phrase and has become firmly adopted by many as a place-name in its own right. ‘The Bay of the Ox-shelter’ may not have quite the same appeal.

Writers have come up with a curious range of interpretations for this popular Iona beauty spot, for example:

‘The Bay of the Ocean Nook’: (E.C. Trenholme, The Story of Iona, David Douglas, 1909); also in M.E.M. Donaldson, Wanderings in the Western Highlands and Islands, 1920).

‘The bay of the twin’s hiding-place’: (Hamish Haswell-Smith, The Scottish Islands, Canongate Books, 1996).

‘The Bay at the back of the Breaking Waves or The Bay of the Nook of Peace’: (John Murray, Reading the Gaelic Landscape, Whittles Publishing, 2014).

The source of these may lie in Dwelly’s dictionary, where a masculine noun ‘samh’ is defined as ‘surge, crest of white billows’, a feminine noun ‘saimh’ as ‘peace, stillness’, and an obsolete plural noun ‘saimh’ as ‘twins, pair’. And Dwelly also has another masculine noun ‘samh’ meaning ‘stink, odour (e.g. of fish)’ which echoes yet another contender, an entry in the Ordnance Survey Name Book:

Camas Cùil an t-Saimh

Applies to a large bay on the west side of Iona, extending from the Spouting Cave to Eilean Didil; signification: ‘Bay of the nook of the suffocating smell’ (OSNB 1868-1878/argyll-volume-37/26)

These surveyors’ notebooks provided valuable local background for the huge task of mapping Scotland, which began in the mid-19th century. In each area the collectors consulted an ‘Authority’ of inhabitants with knowledge of local features and buildings. The ‘Authority’ for Iona comprised five islanders: Archibald MacDonald, postmaster; John MacDonald, Argyll Hotel; Dugald MacCormick, farmer; James MacArthur, farmer; John McLucas, fisherman, Baile Mòr. Three lived in the village and two were crofters in the west end of the island. They will all have been familiar with the regular task of gathering seaweed to fertilise fields and village potato plots. Rights of access to particular shores were jealously guarded. Blows may even have been exchanged as 19th century bard Angus Lamont implied in Oran do’n Chladach Fheamuin, his poem about arguments on the ‘seaweed shore’ –specifically at Ceann Anndraidh at the north end of the Camus. Seaware piled up for any length of time in the several gullies along that bay may well have produced ‘a suffocating smell’. Or perhaps it was the local fellows’ nick-name for the place. Either way, I rather like this down-to-earth explanation.

The above discussion shows that this is a difficult pair of names for our Iona survey to deal with, unless further research yields more clues for one or both places: eg a written form for Culdamh from the 18th century or earlier since, at present, it is hard to be absolutely certain how the original name was spelled and, therefore, what it meant. Or, if a name for the bay prior to 1859 comes to light, that would also be helpful. Perhaps, we should also explore whether the Admiralty used the term ‘an t-saimh’ for ‘ocean’ elsewhere and if, with only an oral source on Iona, they assumed that this was the word they were hearing after ‘camus’.

If the names are linked, the case for which came first appears stronger for Culdamh, a place of many spellings in the past but which has clear links with agriculture and thus with generations of people who lived on Iona. The big bay gave the inhabitants access to fish, driftwood and seaweed and so, for it to be called after the nearest holding to landward also makes sense.

Or, do the two names not actually relate to each other after all?

….

Many thanks for comments, photos and additional information to members of the project team and to Fiona Kyle and Kirsty Hinks, of the Campbell family. And in affectionate memory of Sheila McRae, Anna Campbell and Johnnie Campbell, the Culdamh bard.