‘Architecture is what you do to a building when you look at it.’

(Walt Whitman)

In this blog I want to explore some questions around the spatial organisation of monasteries. This is partly because of the dramatic differences in layout between the Early Medieval monastery on Iona and the later medieval Benedictine monastery. What do these changes mean? What can they tell us about monastic life? Is there an ideological change involved in this difference in layout? Is there continuity?

When you look at a building there are several ways of thinking and talking about it. You can ask what it is made of (wood, stone, bricks etc.), what shape it is (round, square, oblong), what style it is built in (romanesque, baroque, brutalist), does it keep its occupants safe, warm and dry?[1] There is another set of questions we can ask of a building or collection of buildings, and that relates to ‘space syntax’ or ‘spatial depth’. In a series of connected spaces, how many spaces do you have to go through to get from where you are to the one you are going to? How are those spaces arranged? How many ways of getting to your goal are open to you? And of course, you can also ask who gets into any given space: who gets access and who doesn’t, who controls the access to a particular space?[2]

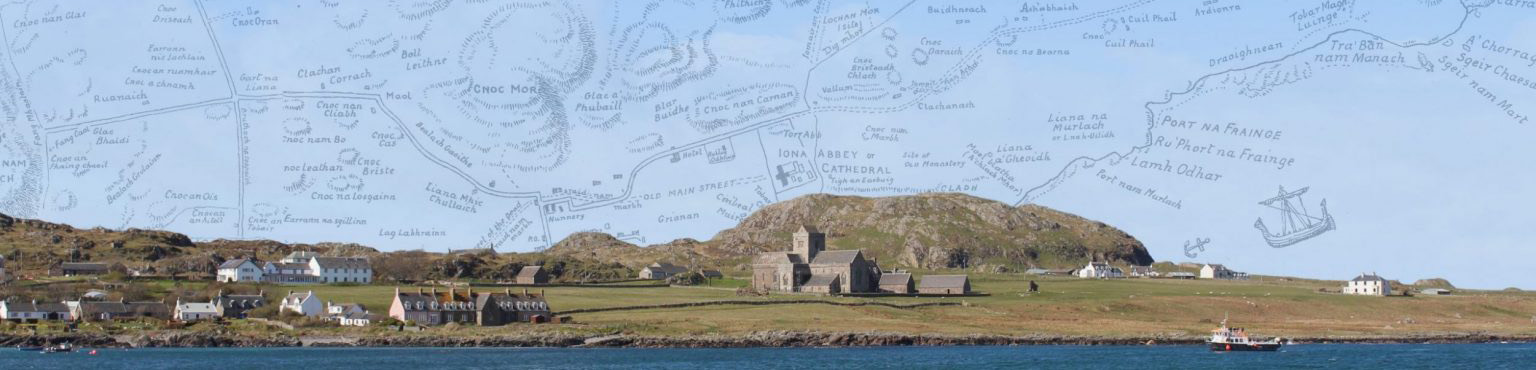

It is perhaps best to illustrate this ‘space syntax’ approach with a couple of plans. Here are two buildings with an identical formal plan, except for the placement of the doors.

Fig 1: spatial depth in two similar building plans

Fig 1: spatial depth in two similar building plans

In Plan A, the only way to get from outside the building (spatial depth = 0) into Room D is to pass through three other rooms, A, B, and C. This fact can be represented on a ‘spatial depth’ graph, as here, by a straight line connecting the outside space through the others to D, which has a spatial depth = 4. In Plan B, by the simple addition of a door between room A and room D, a quite different space syntax appears. There is a ‘branch’ in Room A: you can move straight ahead into Room B, or turn right into Room D. The outcome is a more ‘shallow’ building, no room deeper than spatial depth = 2. And the pattern has a ring structure, rather than the strictly linear arrangement of Plan A. These two plans are very simple, but they are sufficient to give a sense of how this ‘space syntax’ works, and the reader may extrapolate to imagine vastly more complex and ‘deeper’ building forms.

The typical monastic plan

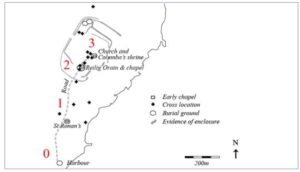

Our expectations of what a monastery is expected to look like are, in the West, very much shaped by later medieval developments: a large rectangular church attached to a cloister-building in which the community’s life is mostly lived, with dormitories, chapter room, refectory, kitchens etc. There may be various out-buildings attached such as the guest-house, workshops etc. This is pretty much what the surviving layout of Iona Abbey looks like today. But it was not like this in the beginning. Hedstrom and Dey have shown that there really was no standard building type or spatial organisation for monasteries in the early medieval period when ‘the line between vernacular and monastic architecture is almost entirely blurred’. Egyptian and Palestinian monasteries are by and large archaeologically indistinguishable from other rural settlements in their respective areas. Urban monasteries, often attached to basilicas and providing the ‘staff’ for those churches, are architecturally just like other urban dwellings. Many monasteries in western Europe began with communities squatting in abandoned rural settlements, villas or old forts. The monastery of Subiaco in the mid-sixth century (supposedly Benedict’s monastery) is a Neronian complex, the original buildings remaining unaltered to accommodate monks, though some essential repairs were carried out. Columbanus’ monks settled at Luxeuil in the 590s in the remains of an old Roman castrum. The one feature that monasteries did tend to share in the early centuries was some kind of overall enclosure, some way of separating the monks from ‘the world’, both practically and symbolically.[3]

Although there was no standard or common plan for monasteries in the West, monastic texts describe the monks’ lives and their spaces in ways which allow us some insight into the way they organised things. We might consider the Rule of St Benedict (RB), for example: a sixth-century text which was certainly known on Iona and treated as authoritative in the early eighth century, and probably in the seventh century too.[4] It describes the monks’ lives together as a community in ways which help us to imagine the organisation of space.

- The whole monastery is surrounded by a claustrum or enclosing device. (RB §4, 67).

- The centre of the monks’ lives is their common prayer, the opus Dei or ‘work of God’, which takes place in the oratorium or ‘prayer house’ (RB §7, 35, 38, 44 etc.). The Rule nowhere refers to this space as an ecclesia or a capella. An individual monk may also enter and pray – ‘not with a loud voice, but with tears and attentiveness of heart’ (in lacrimis et intentione cordis) (§52).

- The monks are to sleep all together in one place (in uno loco) if possible. The word dormitorium is not mentioned, but that is clearly what is envisaged. If the large number of monks makes this impossible they should sleep in groups, ten or twenty to each cella (RB 22).This dormitory must be somewhere near the church, as the monks must rise in the night and enter the church to pray.

- There is a store supervised by the cellarius.

- There is a kitchen, where all the monks are expected to take a turn on kitchen service (officium coquinae), ‘for all are to serve each other’ (RB 35).

- The monks eat together in a refectory. It is presumably near the kitchen.

- There is a separate cella for the sick brothers, with a God-fearing attendant (servitor) who is diligent and caring (RB 38).

The buildings mentioned above serve the inner life of the community, and it is likely that they clustered together. Later in the Rule there is a sequence of chapters about how the monastery organises its dealings with the outside world, and how to protect its own inner life from potential disruption:

- The primary person governing this aspect of life is the doorkeeper (hostiarius) who supervises the gateway (porta) through the enclosure. He is ‘wise and old’ (senes sapiens), and has a cella close to the porta (RB 66).

- Guests are received, as are the poor and pilgrims, with the highest degree of care and concern (RB 53), but there are separate cooking (and presumably eating) arrangements for them, and there is a guest-house (cella hospitum) where they stay. The guest-house is probably not part of the core of the monastery, as the monks are forbidden to converse with them except for the one monk who is in charge of the guest-house.

- A postulant seeking admission to the monastery as a monk is initially treated as a guest for a few days, staying in the cella hospitum, but after that he is admitted to the cella noviciorum where he may meditate, eat and sleep, while his vocation is tested by a senior (RB 58). After some months he may be received into the community. This suggests that there may be some distance between the core parts of the monastery where most of the monks live and the guest-house and novice-house where non-monastics are accommodated.

- Monks who come visiting from other monasteries are to be received, as long as they are content to abide by the customs of the house. They seem to be admitted to the core part of the monastery rather than having to stay in the guesthouse (RB 61), because they are monks.

Finally we might note a more general aspect of the Rule with regard to monks who are craftsmen (artifices) (RB § 57). These will require workshops of various sorts, of course, and it is likely that these will be at the outer edge of the monastic area. This is perhaps confirmed by RB §66 which says: ‘The monastery, if it is possible, ought to be so laid out that all things necessary – that is water, mill, garden, and various crafts (artes diversas) may be exercised within the monastery – so that there will be no need for the monks to go wandering outside, for this is in no way good for their souls.’ Monks will presumably have to go outside the principal enclosure, however, when they are working in the fields. RB § 48 mentions monks gathering the harvest for example, while §41 discusses the monks’ ‘field labour’ (labores agrorum); these are presumably ‘the brothers who are working some distance away and cannot come to the oratory’ (fratres qui omnino longe sunt in labore et non pussunt occurrere … ad oratorium) (RB § 50).

There is another important document which sheds light on the arrangement of monastic space. One of the two authors of the Collectio Canonum Hibernensis (CCH) in the early eighth century was an Iona monk, Cú Chuimne. In the guidance for the layout of a holy place (sanctum locum) we find the following:

On the number of boundaries of a holy place.

A synod placed four boundaries around a holy place, the first into which laymen and women may go, another into which only clergy come. The first is called ‘holy’, the second ‘holider, the third ‘most holy’. The name of the fourth is lacking.There should be two or three boundaries around a holy place, the first into which we do not allow anyone to enter except the saints, for lay men are not allowed in it, nor women, but only clergy; the second into whose streets/paved areas we allow throngs of rustic folk to enter if they are not overly given to wickedness; the third into which we do not even forbid murderers and adulterers to enter, by permission and custom.[5]

These two pictures, appearing as manuscript variants, are rather confused (corrupt?) and not entirely consistent with each other. But they agree in giving an overall impression of a holy place, whether church or monastery, which is arranged according to a hierarchy of holiness. It may imply, though this is not absolutely necessary, a series of concentric enclosures, the holiest place (for the holiest people) in the centre, and decreasing levels of holiness as one moves further out.[6]

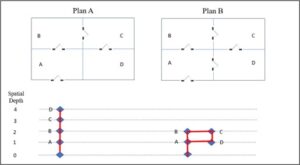

If we combine the general picture offered by RB and CCH above with what we can learn from Adomnán’s Vita Columbae (VC) written in the late seventh century and from archaeology, perhaps we can begin to form a sense of the space syntax of early medieval Iona. In what follows, I will list what seem to me the probable features of this layout, what was located where, and where the boundaries were. This plan, with its four levels of space syntax marked, will help clarify my following remarks.

Fig. 2: suggested subdivisions of the Iona Abbey landscape

Fig. 2: suggested subdivisions of the Iona Abbey landscape

Level 0

Arrivals at the island may be presumed normally to come to the harbour. It is in Level 0, the outermost layer of sanctity, but the whole island is nevertheless a holy place, as VC makes clear, and the abbot of the monastery is shown controlling who has access and who doesn’t, and under what conditions.[7] From the harbour a person arriving may go west, across to the other side of the island. That is the side where Adomnán shows the Iona monks sowing and harvesting their crops on the machair. The west side is also where Adomnán reveals there was a guest-house – the only guest-house he mentions. He calls it a hospitium;[8] RB refers to the guest-house as cella hospitum. The distance of the guest-house from the core of the monastery is significant. It is thirty or forty minutes’ walk, or more depending on where on the west coast the hospitium was located.

There is a mound containing several cist burials, An Eala, on the shore by the harbour, well outside all the monastic enclosures. The RCAHMS monument record of an excavation of this site recorded in 1975 states:

Although many of the skeletons had been greatly disturbed by subsequent burials, It was possible to identify at least forty individuals, with a marked preponderance of females whose average age at death was about forty. Of the eight females whose skeletal remains permitted a determination to be made, none had borne children. It was also noted that neither men nor women exhibited evidence of the hard-manual labour to be expected among a peasant community and none had died by violence. From these conclusions the burials may tentatively be associated with a community of celibate females.

At the time that record was made, it was not possible to obtain radiocarbon dates from the bones, but subsequent investigation has dated at least one of them to the seventh or eighth century, and it is to be hoped that funding will become availble to date others.[9] Some of the graves were cut through a layer of charcoal which has been dated to c.480 x 600. All this may suggest a time-frame for the existence of a community of nuns on the island of Iona, perhaps close to An Eala and the harbour in Level 0. This would fit with a pattern found in other early monasteries where nunneries were founded as ‘suburbs’ or ‘satellites’ of male monastic centres, outside the vallum but not too far away. See for example the nunneries at Clonmacnoise and Armagh; we may also consider Templenaman (‘church of the women’) on the island of Inishmurray, outside the men’s monastic enclosure and located on the shore and beside the harbour.[10]

Level 1

Someone walking north from the harbour towards the abbey would find themselves on a road with stone crosses on either side and, after about 300 metres, at a burial ground and, probably, a church. In later centuries, circa 1200, a community of Augustinian nuns would be founded here, and immediately to the north of the nunnery a church was built about the same time, now commonly called St Ronan’s Church or Teampall Rònain,[11] which served as the medieval parish church for the island. Jerry O’Sullivan’s excavation of that church in 1992 showed that the medieval structure now visible was built over the footings of a much earlier (and smaller) church built of clay-bonded stone covered with white lime-based plaster.[12] That earlier church may be dated ‘any time between the eighth and the twelfth century’, and it was itself built on top of a number of earlier medieval burials which themselves ‘may date to as early as the period of primary monastic settlement on Iona in the mid-sixth century’, though later dates are possible. Sadly there is insufficient bone material in these earliest graves for radiocarbon dating.[13] What is the significance of a church in Level 1, at this site? Was it simply a cemetery chapel for conducting whatever rites were concerned with the burial and commemoration of the dead? Or did it serve as a church for visitors to the island who might not always have been granted access to the main oratorium of the monks, and who could thus be kept at a distance from the core of the monastery?

In addition to the church and roadside crosses in Level 1, it is likely that some farming activities took place along with industrial and food-processing work. Thus in VC ii, 29 a brother went outside the vallum of the monastery (ualum monasterii) to slaughter a cow with a knife. In VC ii, 16, a brother brings a bucket of milk from outside the vallum into the monastery. In VC iii, 23 we find an account of the monastery’s barn, where grain was stored (and perhaps processed) which is clearly outside the monastery in the mind of the author, because the saint ‘left the barn, returning to the monastery’ (horreum egreditur et ad monasterium reuertens). Further farming activity is indicated just outside the north-western section of the vallum, also in Level 2, by the presence of coprophilic insect-remains in the bottom of the ditch, which appear to be part of the sweepings from the floor of a building where cattle were kept (close to where the Macleod Centre stands today). They were deposited between AD 580 and 770.[14]

Level 2

The early medieval road crosses the outer vallum to bring us into Level 2. There is a cross on the east side of the road close to the point where the road crosses this important boundary. Level 2 is defined on the south side by what we might call the ‘outer vallum’, and on the north side by what we might call an ‘inner vallum’ (see plan above). There may be a problem with this description, however. The two valla may not have served concurrently; it is possible that the inner one is the original, while the outer one represents a later expansion of the monastic enclosure. Against this is the fact that Level 2 has a church building (St Oran’s Chapel, in Gaelic Teampall Odhrain) and a burial ground (Rèilig Odhrain), just like Level 1 and Level 3. The building now standing there is twelfth-century, but the burial ground pre-dates it, and there may well have been an earlier chapel at the site as well (just as there was at Teampall Rònain in Level 1), a suggestion somewhat supported by the presence close to Teampall Odhrain of a fine stone cross, ‘St Oran’s Cross’, dating to the mid- to late eighth century.[15]

The later medieval tradition that most early medieval kings of Scots were buried here is quite unreliable, though it was evidently used as a burial site for secular chiefs of various sorts in later generations, and quite possibly for high status laymen (including a handful of kings who were buried on Iona) in the early medieval period.[16] The presence of the burials of laymen (and a possible burial chapel) in this period within the outer vallum but outside the inner vallum suggests a careful demarcation and separation, in death as in life, between monks and laymen, just as the outer vallum may mark a demarcation between the laymen buried in Rèilig Odhrain and the women buried in the grounds of Teampall Rònain.

There are records of two small burial grounds at the north end of Level 2 enclosure, just inside the vallum, but there is no reason to think they were in use in the early medieval period.

In the 1380s, John of Fordun refers to a ‘sanctuary’ or refugium on Iona (II, x), but does not say where it is.[17] Pennant, however, refers to it thus: ‘the burying-place of Oran ….the precincts of these tombs were held sacred, and enjoyed the privileges of a Girth or sanctuary. These places of retreat were by the antient Scotch law, not to shelter indiscriminately every offender, as was the case in more bigotted times in catholic countries: for here all atrocious criminals were excluded; and only the unfortunate delinquent, or the penitent sinner shielded from the instant stroke of rigorous justice.’[18] This may not reflect accurately the conduct of sanctuary proceedings on Iona, but it may echo a reliable local tradition that Rèilig Odhrain was indeed the place of refuge on the island, in a way which medieval writers fail to indicate.

Level 3

Moving up the road from Level 2 (Rèilig Odhrain) into Level 3, one crossed the inner vallum. Stone crosses marked the transition, one (at least) to the south of the vallum, and one to the north. We may safely assume, I think, that this was the area (the open perhaps partially paved space which Adomnán calls the platea) where routine elements of monastic common life took place: dormitories, refectory and kitchen. There is also some evidence of craft work on the outer edges of Level 3: a spread of slag from iron-working, for example, to the south and south-west of the enclosed area, and evidence of glass-working and non-ferrous metal moulding.[19] The wattle hut on Tòrr an Aba (‘hill of the abbot’) to the west of the present abbey church was burned but left some charcoal remains which have been dated to a period which actually embraced Columba’s lifetime, and may actually be the hut described by Adomnán where Columba wrote manuscripts in his own hand and gazed out over his monastery.[20] It was given ritual significance in the early medieval period by the erection of a cross at the site of the hut, whose base still survives.

Level 4

Though too small to be marked on the plan (Fig 2 above), it is likely that the central part of Level 3, containing the church or oratorium and the reputed site of St Columba’s burial (which eventually had a tiny shrine chapel built over it), was seen as a ‘special area’, which we might call Level 4. It may have had some kind of symbolic or practical boundary around it – a wall or fence. The oratorium must be presumed to underly the present church building, erected circa AD 1200. It may even be that the high altar of the abbey church overlies the site of the altar of the original church – given the conservatism and the sense of significance of space and materiality which played such an important part in the lives of early medieval monks.

Level 5

The lives of the monks within the oratorium consisted largely of the performance of the divine office – a sequence of psalms, canticles, readings and prayers, which punctuated the entire working day of the monastery, and interrupted the nights as well. But at the east end of the oratorium was a special location: the altar in its sanctuary area, perhaps demarcated by rails, a beam, a rising step, or even a screen of some sort. This should be seen as a ritually distinct area, the sanctum sanctorum or ‘holy of holies’ where the eucharist, the ultimate mystery of the faith, was enacted; it is also the spot where Columba lay down and died in the arms of his brethren on 9 June 597.[21]

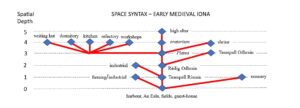

It is now possible to offer a tentative diagramatic representation of the space syntax implied by the foregoing description.

Fig. 3: space syntax of early medieval Iona

This diagram, with its clear central axis and branches off reflects the movement through space of the people who ‘used’ Iona – monks, pilgrims, guests, penitents. The movement may have been stopped at various points (before landing on the island, between Level 1 and Level 2, or between Level 2 and Level 3) and at various times for different categories of person. At other times these barriers may have been lifted for particular reasons. The diagram bears an interesting likeness to another one (see below), representing the space syntax of the thirteenth-century Benedictine Abbey. It is as if the organisation and discipline of the early medieval monastery, which was expressed in a more open plan and with simple (mostly unicameral) separate buildings, is now expressed in a single built complex structure which seeks neverthess to maintain aspects of the early medieval space syntax. It does so because it seeks to maintain the monastic discipline which that syntax embodied, in spite of having adopted a completely different architectural idiom in which to do so.

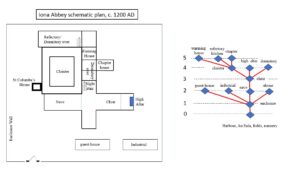

Fig. 4: Schematic plan and space syntax of Iona Abbey, c. 1200 AD

(note that the the guest-house and industrial buildings, while they would

have been outside the main building, are not located ‘in position’ in this plan)

[1] Andy MacMillan, an architect in Jack Coia’s practice in Glasgow in the 1960s and 70s, was once asked why all his buildings leaked (many of them churches): “I think it’s because we have to build them outside in the rain.”

[2] For an introduction to this form of analysis, see B. Hillier and J. Hanson, The Social Logic of Space (Cambridge, 1984); also Thomas A. Markus, Buildings and Power: Freedom and Control in the Origin of Modern Building Types (London, 1993), 12-18. For the application of this mode of analysis to Iron Age brochs in Scotland see Sally M. Foster, ‘Analysis of spatial patterns in buildings (access analysis) as an insight into social structure: examples from the Scottish Atlantic Iron Age’, Antiquity 63 (1989), 40-50.

[3] Darlene L. Brooks Hedstrom and Hendrik Dey, ‘The Archaeology of the Earliest Monasteries’, in Alison I. Beach and Isabelle Cochelin (eds), The Cambridge History of Monasticism in the Latin West (Cambridge, 2020), 73-96.

[4] Gilbert Márkus, ‘The Rule of St Benedict and the “Celtic Church”’, Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies 87 (2024), 1-30.

[5] H. Wasserschleben (ed.), Die Irische Kanonensammlung (Leipzig, 1885), 175-6 (XLIV, 5).

[6] It is the model explored by David Jenkins, Holy, holier, holiest: the sacred topography of the early medieval Irish church, (Turnhout, 2010) in series Studia traditionis theologiae.

[7] Gilbert Márkus, ‘Four Blessings and a Funeral: Adomnán’s theological map of Iona’, The Innes Review 72 (2021), 1-26.

[8] VC i, 48. Though hospitium can just mean ‘lodging’, Adomnán refers to the crane in the story as prescitae hospitae, ‘a foreseen guest’, making clear the bird’s status in the monastery.

[9] Adrián Maldonado, ‘Christianity and burial in late Iron Age Scotland, AD 400-650’, unpublished PhD thesis, available at http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2700, p. 245.

[10] See Gilbert Márkus, ‘Replicating a Sacred Landscape: the cult of Saint Odrán in Scottish Place-Names’, Journal of Scottish Name-Studies 15 (2021), 10-31, at 14-15. Note that the name Cladh nan Druineaach ‘burial ground of the embroiders’, a short distance south of An Eala, suggests another possible burial ground, and perhaps one associated with women. But I know of no archaeological evidence to confirm the presence of early medieval burials here.

[11] The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, Argyll, volume 4: Iona (Edinburgh, 1982), 251-2. For discussion of who the original patron saint of the church may actually have been, see Thomas Owen Clancy’s illuminating blog: https://iona-placenames.glasgow.ac.uk/the-church-of-teampull-ronain-his-or-hers/

[12] Jerry O’Sullivan, ‘Excavation of an early church and a women’s cemetery at St Ronan’s medieval parish church, Iona’, The Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 124 (1994), 327-365.

[13] O’ Sullivan, ‘Excavation’, 352. It is worth noting that later burials around Teampall Rònain are entirely, where sex can be determined, of women and children; this may not reflect, however, gender segregation in the earlier period.

[14] See Márkus, ‘Four Blessings and a Funeral’, 13, for discussion. Also Samantha E. Jones, Enid P. Allison, Ewan Campbell, Nick Evans, Tim Mighall and Gordon Noble, ‘Identifying social transformations and crisis during the pre-monastic to post-viking era on Iona’, Environmental Archaeology (2020). 1-25, at 14-16.

[15] RCAHMS, Argyll 4: Iona, 192-197. The name is modern, suggested by the fact that it was first located in Rèilig Odhrain close to Teampall Odhrain.

[16] James Fraser, Iona and the burial place of the kings of Alba (Cambridge, 2016); Ewan Campbell and Adrián Maldonado, ‘A new Jerusalem “at the ends of the earth”: Interpreting Charles Thomas’s excavations at Iona Abbey’, The Antiquaries Journal (2020), 1-53, at 33. The legend gave rise to the name Iomair nan Righ, ‘the ridge of the kings’, which first appears in 1771. For further discussion of this name, see https://iona-placenames.glasgow.ac.uk/names-of-the-month/ for May 2024.

[17] Thomas Hearn (ed.), Johannis de Fordun Scotichronicon Genuinum (Oxford, 1722), vol. 1, 82 (Bk. II, Ch. 10).

[18] Thomas Pennant, A Tour in Scotland and Voyage to the Hebrides, MXCCLXXII (London, 1774), 288.

[19] Campbell and Maldonado, ‘A New Jerusalem’, 39.

[20] Elizabeth Fowler and P. J. Fowler, ‘Excavations on Torr an Aba, Iona, Argyll’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 118( 1988), 181-201. For radiocarbon dating see Campbell and Maldonado, ‘A New Jerusalem’, 18.

[21] VC iii, 23. See also Márkus, ‘Four Blessings and a Funeral’, 23-24.