We are grateful to Mike Small for providing this guest blog sharing his work on the lost wells of Iona.

Mike Small writes:

I’ve been a regular visitor to Iona all my life and explored it more by sea than land. But lockdown and newly digitised maps available from the National Library of Scotland led me to research the lost wells of Iona, many of which have disappeared, off the map and out of our consciousness.

Some have dried up, some have been removed from maps, some have been concreted over. The process of erasure has many causes, among them the anglicisation of place-names and maps, improvements to water supplies, the Reformation. This is part of a wider piece of research, that will take a broader look at the historical and religious context of these sites, to be published next year.

I’ll here look at six of the eighteen wells I’ve identified, some of which are located on old maps but no longer appear to exist, some of which you can still visit and some which have disappeared completely.

Tobar na Gaoithe Tuath (Grid reference: NM276251[1])

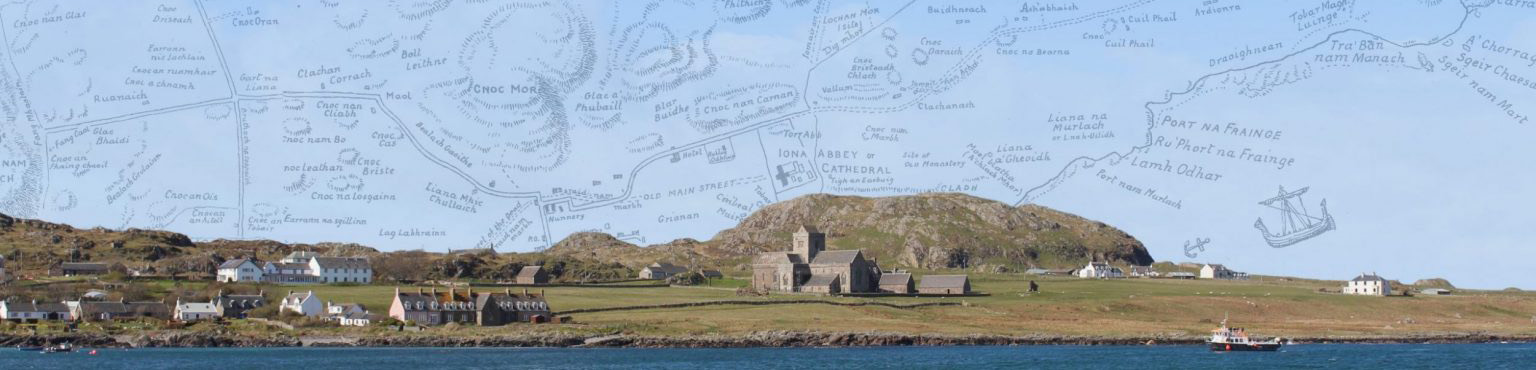

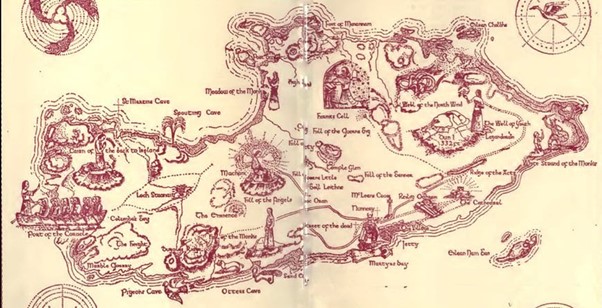

A sacred well site, meaning Well of the North Wind, that used to have far more prominence on maps and signage. On this map it is given the same prominence as other major places of interest:

F. Marian McNeill wrote that: ‘This is one of the magic wells of antiquity. It lies north of Cnoc nam Bradhan, not far from the Hermit’s Cell. Here, in olden times, sailors and others brought offerings to charm up a wind from the north.’[2] Mairi MacArthur has written:

…the island abounds in wells. Tobar Magh Luinge … above Traigh Bàn nam Manach at the north end … Tobar na Gaoithe Tuath, south-west of Dùn I, means ‘well of the north wind’ and there were once south, east and west wind wells, their sites now forgotten. Certain people were said to have been endowed with the ability to raise the appropriate wind by chanting a rhyme at the well. And Tobar a’Cheathain, just below the Cathedral, was believed to have healing powers.[3]

And for writer Kenneth Steven, wells:

were seen as holy by the early Celts, long before the Christian Gospel came to Ireland. They were sacred long before that, for what could be more magical than pure clear water bubbling from the darkness of the earth? And that water would be more than likely full of precious minerals bringing wholeness and healing … With the arrival of Christianity came a faith that had plenty to say about wells and healing. The old processions to springs on certain days were not forbidden, rather they were incorporated into the new order of things. Springs and wells were christened, they were named after saints and their healing power ascribed to them.[4]

In fact there’s now some evidence that the benefits might be real.[5] Dr Celeste Ray, of Ireland’s County-by-County Holy Wells project, states there may be evidence to support what she calls ‘folk science’: ‘…If the waters have sulphur in them, that’s good for skin conditions; if they contain magnesium that’s good for muscle function and the heart; if the well is iron-rich that’s good for people who are anaemic.’

Tobar Magh Luinge (Grid reference: NM291258)

It was previously thought that Tobar Magh Luinge was associated with Moluag, a well-known saint from the time of Columba. However, it is now thought more likely that ‘the plain of the ship’, which is the correct translation, refers to the Columban daughter-house of the same name on Tiree – not so far by boat from the north end of Iona where this spring of water was located and where it was still visible in living memory. The well site was identified by islander Mhairi Killin from information provided by local crofter, the late Iain Dougall.

Tobar na h-Aoise (Grid reference: NM283252)

Close to the summit of Dùn I is a well whose Gaelic name means ‘Well of Age’ but which, in recent times, has been misnamed the ‘Well of Eternal Youth’. In 1893 a visitor, Malcolm Ferguson, spent a week on Iona. In the book of his trip, A Visit to Staffa and Iona, Ferguson wrote that his guide, an islander of the same name who lived at Cuil Phail croft below Dùn I, referred to this well as ‘the marvellous Wishing Well of Iona, Fuaran-na-aois ie Well of Age’. The well is probably the best-known, by its proximity to the summit of Dùn I and by its mentions in the writing of Fiona MacLeod (pen name of William Sharp).[6]

Tobar a’ Cheathain (Grid reference: NM287244)

This photo was taken at Tobar a’ Cheathain (Well of Ceathan or Kian), with Alex for scale. It is unmarked, just below the Abbey and near to St Mary’s Chapel.[7] It was a healing well, from which old people often requested a drink on their deathbed. A Gaelic verse, quoted in the Native Steam-boat Companion (1845) asks for no sustenance except a drink from the spring-well of Ceathain. S’cha mho dhiarr e ra ol, Ach uisge mor a Ceathain.[8]

Tobar Glac a’ Choilich (Grid reference: NM264218)

In May 2021 I walked to the south end to try and triangulate references from digitised Gaelic maps, recorded interviews of crofters from the 1970s and my own research, in search of Tobar Glac a’ Choilich. The first edition of the Ritchie map recorded Glac a’ Chulaidh (‘gully of the boat or coble’) but in the 2nd edition the Corrigenda states that this should be Glac a’ Choilich/gully or dell of the cockerel. The names of both the gully, and the well located in the gully, were changed in subsequent editions. In Gaelic coileach doesn’t always mean a farmyard cockerel, sometimes a moorland bird such as woodcock.

I was in search of a shape in the landscape that might look like a bird or a cockerel. On a very fine day I searched the cliffs at the top of the gully above Columba’s Bay. Descending after some hours I saw a well and scrambled down. This is the rock that marks the well. I think it has a distinct bird shape with the top left being the beak and head and the bottom right being the tail and wings.

The well was deep and cool despite a very dry period.

Triumphant I carried on down the cliffs before I made another discovery.

Beneath the Well of the Dell of the Cockerel lay another well.

Tobar na Gaoithe a Deas (Grid reference: NM264217)

This well is beneath a sheer rock face that orients and projects south at the island’s most southerly tip, just above St Columba’s Bay.

The location and view is remarkable and the rock formation is astonishing. I believe this is the Well of the South Wind, ‘lost’ for a very long time. As I left, trying to think of how I could remember the precise location, I looked back up at the cliffs to this cloud formation.

The re-discovery and re-location of these ancient wells feels like an important remembering of something lost. On completion of further research I intend to map and publish further notes in the coming year. If you have information about these or other wells please get in touch.

References:

[1] Grid references are approximate.

[2] F. Marian McNeill, Iona. A History of the Island (Blackie & Son, 1st edn 1920, 4th edn 1954; Lochar Publishing, 7th edn 1991), 72.

[3] E. Mairi MacArthur, Iona. The Living Memory of a Crofting Community (Edinburgh, 1990, 244; 2nd edn, 2002 & 2007), 285.

[4] Kenneth Steven, Iona The Other Island (Saint Andrew Press, 2017), 84.

[5] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-56216763

[6] Fiona MacLeod, Iona (first published by Chapman & Hall, 1910; Floris Books, 1982), 31-32.

[7] Canmore ID 21618 https://canmore.org.uk/

[8] RCAHMS The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, Argyll: an inventory of the monuments vol. 4: Iona (Edinburgh, 1982), 279.