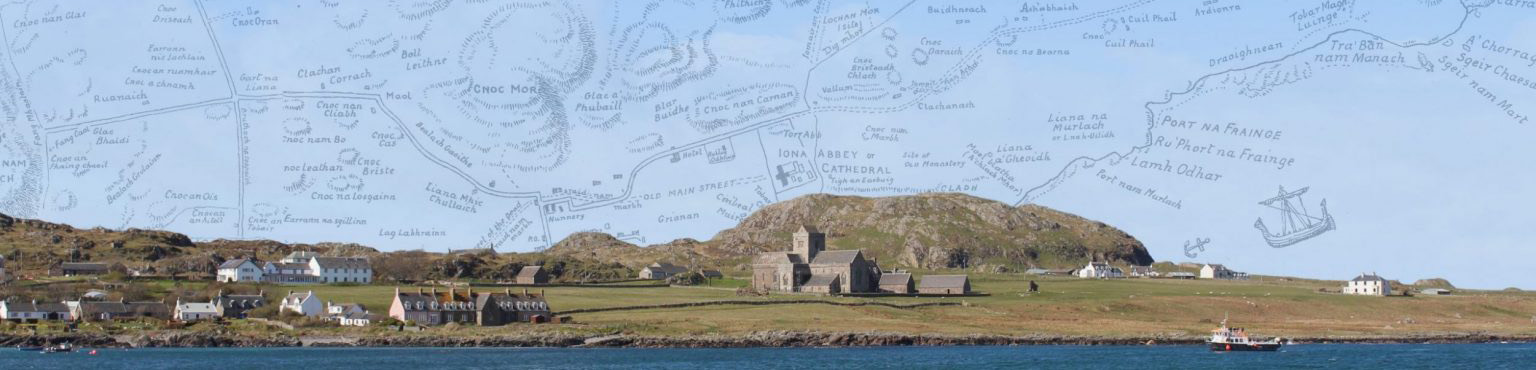

In a previous blog, Thomas Clancy discussed the conundrum of the lack of evidence for the cult of St Brigit on Iona before ca. 1900, despite the later presence of stories associating her with the island during the Celtic Revival. In this blog I will explore these traditions and their potential origins.

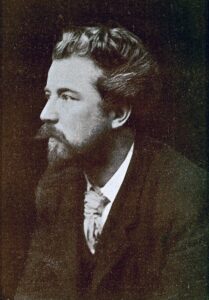

William Sharp, writing under the pen-name Fiona Macleod during the late 19th and first years of the 20th century, is perhaps the most prolific, and potentially first, author to directly place St Brigit on Iona. It is, however, important to remember that he has taken considerable creative liberty when writing about the history of Iona. The tense relationship between Sharp/Macleod and the Gaelic world has recently been explored by Duncan Sneddon, who describes Macleod’s ‘rhetorical use of the imminent demise of Gaelic to facilitate its aesthetic appropriation by members of the economically and politically

dominant Anglophone majority to which Sharp belonged’.

In multiple literary works Sharp/Macleod writes of ‘St Bride’ growing up on the slopes of Dùn Ì. One day she falls asleep after drinking from the ‘Fountain of Youth’ and upon waking, discovering that she is the daughter of an inn-keeper in Bethlehem. Having provided shelter to Mary and Joseph she nurtures Christ while Mary sleeps. At the end of the story she is returned to Iona. An abbreviated version is included at the end of this blog.

This story likely also the context in which another place-name, Tobar na h-Aoise ‘Well of age’, becomes linked to St Brigit. The name refers to a natural pool at the summit of Dùn Ì with possible artificial banks added (1996 NTS Survey). By the early 20th century, the well in question had gained a reputation in traveller literature as a ‘well of youth’ and this is undoubtedly the ‘Fountain of Youth’ featuring in Macleod/Sharp’s account.

Another instance of creating a link between St Brigit and Iona can be found in one of the paintings of John Duncan (see image). The painting depicts a scene of angels carrying St Brigit to Bethlehem over the ocean. In the background of the painting, Iona Abbey is visible.

Despite the later persistence of these stories, is important to note that there appears to be a complete absence of local Hebridean folklore linking St Brigit to Iona. Some of the accounts are, however, loosely linked to the tradition of the saint as the foster-mother of Christ; muime Chrìost or muime Dhè, well-attested in oral tradition and published folklore collections, and with roots stretching as far back as the Middle Ages (also see previous blog on St Brigit). Indeed, Macleod/Sharp (c1896, p. 48) notes that ‘this legendary romance is based upon the ancient and still current (though often hopelessly contradictory) legends concerning Brighid, or Bride, commonly known as “Muime Chriosd”—i.e., the Foster-Mother of Christ.’ Alexander Carmichael (CG vol 1, pp. 164-177) in his ‘genealogy of Bride’ records several hymns in which Brigit is the foster-mother of Christ:

Loinneadh na Ban-naomh Bride,

Lasair dhealrach oir, muime chorr Chriosda.

Bride nighinn Dughaill duinn,

Mhic Aoidh, mhic Airt, mhic Cuinn,

Mhic Crearair, mhic Cis, mhic Carmaig, mhic

Carruinn.

The genealogy of the holy maiden Bride,

Radiant flame of gold, noble foster-mother of Christ,

Bride the daughter of Dugall the brown.

Son of Aodh, son of Art, son of Conn,

Son of Crearar, son of Cis, son of Carmac, son of

Carruin.

In Carmichael’s version, Bride was ‘the daughter of poor pious parents, and the serving-maid in the inn of Bethlehem before aiding Mary in the birth of Christ. Similarly, an account recorded in South Uist by Donald MacIntyre (1959, TAD ID 42045) Brigit comes upon Mary giving birth and aids her. It is worth noting that in these traditions, Brigit is already in Bethlehem, and there seems to be no mention of her Hebridean origins. So, where do the stories of Brigit growing up on Iona come from?

It does not seem too far-fetched to suggest that when envisioning a Hebridean St Brigit who was carried to Bethlehem by angels or wakes up from a dream, she would be found at one of the holiest places in Gaeldom; Iona. Here it is worth pointing out that Iona as a Gaelic Jerusalem has been discussed in other contexts, notably by Ewan Campbell and Adrián Maldonado (2020): ‘Recent theological discourse has emphasised the leading role of Iona, and particularly its ninth abbot, Adomnán, in developing the metaphor of the earthly monastery as a mirror of heavenly Jerusalem.’ Whether or not Macleod/Sharp was aware of this, he clearly made a similar connection between Iona and Bethlehem: ‘[I] dream that this may be upon Iona, so that the little Gaelic island may become as the little Syrian Bethlehem’ (Macleod 1900, p. 99). Ultimately, this may have been the original prompt for some of the narratives linking St Brigit to Iona.

As noted in the previous blog on St Brigit, despite the tendency to associate Brigit with a pre-Christian goddess, it is clear that she was a real historical woman. Nevertheless, when St Brigit is discussed in a Hebridean context, some authors are particularly prone to blur the lines between saint and goddess. According to folklorist Marian McNeill (1957): ‘Between the pagan goddess and the historical saint there appears yet another Bride — St. Bride of the Isles — who is a purely legendary figure symbolising the transition from goddess to saint’. Thus, in Donald Mackenzie’s[1] (1917, pp. 33-49) telling of ‘The Coming of Angus and Bride’, Bride is ‘the lady of summer growth’, a princess held captive by ‘Beira, Queen of Winter’ until she is rescued to bring about Spring:

When softly blew the south wind o’er the sea,

Lisping of springtime hope and summer pride,

And the rough reign of Beira ceased to be,

Angus the Ever-Young,

The beauteous god of love, the golden-haired,

The blue mysterious-eyed,

Shone like the star of morning high among

The stars that shrank afraid

When dawn proclaimed the triumph that he shared

With Bride the peerless maid.

Then winds of violet sweetness rose and sighed,

This type of Celtic Revival literature tends to mingle motifs from various sources. Despite this version of Bride having little direct connection to the saint, in Mackenzie’s account creatures and objects frequently linked with St Brigit like the oystercatcher and milk are present.

There seems to be a common theme in these stories. Despite place-names like Dùn Ì, Tobar na h-Aoise and Port a’ Churaich being connected to the saint, there are no actual place-names on Iona directly commemorating St Brigit. This may seem rather strange considering that hagiotoponyms are one of the strongest indicators of the cult of saints in the landscape. But, considering that these stories are relatively recent and do not appear to have been prevalent in a local context, this may not be surprising. In light of this, we may argue that the Celtic Revival authors discussed here have deliberately selected existing sites and names of note on Iona which are used as anchors for these stories, thus potentially adding an aura of authenticity. This may also have aided in the promotion of these sites as popular destinations for visitors by providing a physical destination linked to the legend of St Bride.

Here it is worth briefly thinking about the continued significance of these traditions, despite their relatively late date. The stories have undoubtedly influenced the Iona presented to tourists visiting the island to a certain degree. This is clearly visible in content produced specifically for the consumption of tourists. For example, according to the Visit Mull & Iona[2] website:

The Well of Eternal Youth, a natural pool in the cleft of rocks just below the Cairn towards the North, is associated with the 6th Century St Brigid of Ireland. In Gaelic “Hebrides” means the Islands of Bride or Brigid, and Iona is just one of these. St Brigid appears in Celtic Myths as having blessed the little pool while visiting Iona on the Summer Solstice. The blessing was to bring healing and renewal to all that came to seek a new beginning in their lives. You cannot visit this place without splashing your face with the water from this pool!

Similarly, the story of Tobar na h-Aoise has continued to evolve through the online world via blogs and tourist websites: this is in many ways a continuation of what we see in the 20th century, but often without a publisher to rein in the author. New Age spiritualism is particularly prominent. One author writes: ‘The “Well of Eternal Youth” is a Holy Well in the ancient Celtic tradition of holy wells. It is a blessing to be able to sit by the Well and consider its holy and sacred nature. This well is historically connected to the great Celtic Goddess Brighid.’ Such accounts largely appear to be the product of the 20th-century material presented here.

Despite their relatively recent history, it is clear that the 20th and 21st century traditions associated with Dùn Ì and Tobar na h-Aoise have resulted in these sites becoming focal points for a perceived connection between St Brigit to Iona.

I have argued here that Macleod/Sharpe was ultimately responsible for the making this link widespread, but it is clear that multiple authors during the first half of the 20th century incorporated existing motifs into their imagined version of St Brigit and Iona, and in doing so, creating something completely different.

From Macleod/Sharp The Divine Adventure (1900) and The Washer of the Ford (c1896):

In my legendary story I tell of how one called Dùghall, of a kingly line, sailing from Ireland, came to be cast upon the ocean-shore of Iona […] The frail coracle in which he and others had crossed the Moyle had been driven before a tempest, and cast at sunrise like a spent fish upon the rocks of the little haven that is now called Port-a-Churaich. All had found death in the wave except himself and the little girl-child he had brought with him from Ireland, the child of so much tragic mystery […] the Arch-Druid of Iona approached, with his white-robed priests. A grave welcome was given to the stranger. While the youngest of the servants of God was entrusted with the child, the Arch-Druid took Dùghall aside and questioned him. It was not till the third day that the old man gave his decision. Dùghall Donn was to abide on Iona if he so willed; but the child was to stay […] The child, too, was to be named Bride, for that was the way the name Bridget is called in the Erse of the Isles […] So was it, from that day of the days. Dùvach took a wife unto himself, who weaned the little Bride, who grew in beauty and grace, so that all men marvelled […] Bride lived the hours of her days upon the slopes of Dûn-I, herding the sheep, or in following the kye upon the green hillocks and grassy dunes of what then, as now, was called the Machar. The beauty of the world was her daily food. The spirit within her was like sunlight behind a white flower. The birdeens in the green bushes sang for joy when they saw her blue eyes. The tender prayers that were in her heart were often seen flying above her head in the form of white doves of sunshine.

Not far from the summit of Dun-I is a hidden pool, to this day called the Fountain of Youth. Hitherward she [Bride] went, as was her wont when upon the hill at the break of day, at noon, or at sundown […] She had put her lips to the water, and had started back because she had seen, beyond her own image, that of a woman so beautiful that her soul was troubled within her, and had cried its inaudible cry, worshipping […] The song of the mystic bird grew wilder and more sweet as she drew near. For a brief while she hesitated. Then, as a white dove drifted slow before her under and through the quicken-boughs, a dove white as snow but radiant with sunfire, she moved forward to follow with a dream-smile upon her face and her eyes full of the sheen of wonder and mystery, as shadowy waters flooded with moonshine. And this was the passing of Bride, who was not seen again of Dùvach or her fosterbrothers for the space of a year and a day […] When the strain of the white merle ceased, though it had seemed to her scarce longer than the vanishing song of the swallow on the wing, Bride saw that the evening was come. Through the violet glooms of dusk she moved soundlessly, save for the crispling of her feet among the hot sands. Far as she could see to right or left there were hollows and ridges of sand; where, here and there, trees or shrubs grew out of the parched soil, they were strange to her. She had heard the Druids speak of the sunlands in a remote, nigh unreachable East, where there were trees called palms, trees in a perpetual sunflood yet that perished not, also tall dark cypresses, black-green as the holy yew. These were the trees she now saw.

[Bride realises that her childhood on the ‘cool green isle’ of Iona was only a dream, and that she is the daughter of an inn-keeper in Bethlehem]

When she went to the door she saw a weary grey-haired man, dusty and tired. By his side was an ass with drooping head, and on the ass was a woman, young, and of a beauty that was as the cool shadow of green leaves and the cold ripple of running waters. But beautiful as she was it was not this that made Bride start: no, nor the heavy womb that showed the woman was with child. For she remembered her of a dream—it was a dream, sure—when she had looked into a pool on a mountain-side, and seen, beyond her own image, just this fair and beautiful face, the most beautiful that ever man saw […]

“Can you give us food and drink, and, after that, good rest at this inn? Sure it is grateful we will be. This is my wife Mary, upon whom is a mystery: and I am Joseph, a carpenter in Arimathea.” “Welcome, and to you, too, Mary: and peace. But there is neither food nor drink here, and my father has bidden me give shelter to none who comes here against his return.” […] Then without a word she turned, and beckoned them to follow: which, having left the ass by the doorway, they did. “Here is all the ale that I have,” she said, as she gave the flagon to Joseph:

“and here, Mary, is all the water that there is. Little there is, but it is you that are welcome to it.”

[…]

The man Joseph was weary, and said he was too tired to seek far that night, and asked if there was no empty byre or stable where he and Mary could sleep till morning. At that, Bride was glad: for she knew there was a clean cool stable close to the byre where her kye were: and thereto she led them, and returned with peace at her heart.

[…]

Lightly they pushed back the door. When they saw what they saw they fell upon their knees. Mary sat with her heavenly beauty upon her like sunshine on a dusk land: in her lap, a Babe, laughing sweet and low. Never had they seen a Child so fair. He was as though wrought of light. “Who is it?” murmured Dùghall Donn, of Joseph, who stood near, with rapt eyes. “It is the Prince of Peace.” And with that Mary smiled, and the Child slept. “Brigit, my sister dear “—and, as she whispered this, Mary held the little one to Bride. The fair girl took the Babe in her arms, and covered it with her mantle. Therefore it is that she is known to this day as Brigde-nam-Brat, St Bride of the Mantle. And all through that night, while the mother slept, Bride nursed the Child with tender hands and croodling crooning songs.

References

Campbell, Ewan & Maldonado, Adrián, 2020. ‘A New Jerusalem “at the ends of the earth”: Interpreting Charles Thomas’s excavations at Iona abbey 1956-63’, Antiquaries Journal, vol. 100 (2020).

CG=Carmichael, Alexander. 1900. Carmina gadelica, vol. 1 (Edinburgh).

MacArthur, E. Mairi. 1990. Iona: The living memory of a crofting community, 2nd ed (Edinburgh).

Mackenzie, Donald A. 1917. Wonder tales from Scottish myth & legend (London).

Macleod, Fiona. c1896. The washer of the ford, and other legendary moralities (Edinburgh).

Macleod, Fiona. 1900. The Divine Adventure Iona (London).

McNeill, Marian. 1957. The silver bough, vol. 2 (Kindle ed).

[1] Mackenzie (1917, p. 19) writes that ‘On “Bride’s Day “, the first day of the Gaelic Spring, offerings were made to earth and sea. Milk was poured on the ground, and the fisher people made porridge and threw it into the sea so that the sea might yield what was sought from it — lots of fish, and also seaweed for fertilizing the soil. In some parts of the Hebrides the sea deity to whom the food offerings were made was called “Shony”.’ This tradition was also recorded in Iona by Carmichael in the 19th century, but according to him, this took place on Thursday before Easter (MacArthur 1990, p. 237).

[2] The local destination marketing organisation (DMO) for the islands of Mull and Iona. See ‘Dun I and the Well of Eternal Youth’