List of Iona place-names beginning with 'A'

A’ Chama-Leòib

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Coastal

Grid reference: NM2900126182

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 1m

A’ Charraig Fhada

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Coastal

Grid reference: NM2863124064

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 2m

Elements: G an + G carraig + G fada

Translation: ‘the long rock’

Description:

A string of large boulders just north of the ferry slipway and pier. Until a proper slipway was built in 1850 (MacArthur 1990, 102), this outcrop served as a rough landing quay for locals, and for visitors rowed ashore from paddle steamers (see e.g. Head 1837; Maxwell 1857, quoted below). Iron rings to which ropes were tied are still visible on parts of the rock, but the feature is much diminished from its 19th-century length. It is labelled "Old Pier" on the OS 6" 1st edition map from 1881.

Colin MacVean wrote of emigrants setting off from the island from Port Rònain in 1847: ‘The ship, which had previously embarked the emigrants from Mull, lay at anchor in the bay and the boats waiting those from Iona were at the Carraig Fhada while collected on the beach were most of our islanders.’ (Colin MacVean 1899 [Oban Times 4 March 1899] cited in MacArthur 1989 vol. 1, p. 243) His illustration of the village at Iona, published in 1857, shows the feature very clearly (illustration from Maxwell Iona and the Ionians 1857, frontispiece)

Although he does not name the feature, Sir George Head (the Assistant Commissary-General), in his account of his visit to Iona, gives perhaps the best description of what it was like to land on A’ Charraig Fhada for the uninitiated:

“On arriving within a few fathoms of Iona, the channel being about a quarter of a mile wide, the Highlander's anchor was dropped, and we went on shore in a boat; the water the whole way from the vessel being resplendently clear, and rendered still more pellucid in appearance by the whiteness of the sand below, and the huge blocks of granite rock, that here and there protrude from the bottom . We landed upon a flat shoal of this material, which circumstance, as the tide happened to be low, and several ladies, some of them old ones, belonged to our party, might be called inauspicious. A more perilous and slippery path, under the ordinary contingencies of every day life , is rarely encountered. Sometimes it was necessary to step across deep chasms, with no better footing on the opposite side than a rudely pointed fragment of stone; at others we proceeded along apparently flat, even pavement, abounding in watery snares for the unwary, and from which, in fact, caution the most vigilant was insufficient protection. Here some of the party dropped mid-leg deep into hidden pools, covered deceitfully by the broad slippery leaves of sea-weed; others, squeezing under their feet the bloated bags or cists attached to some marine plants, squirted water as high as their own and their neighbours’ heads, or still higher, bespattering their clothes and faces; and one or two persons, too confident in their activity, rolled over on their backs, and got a sound ducking. Gallantry itself was paralyzed as regarded the ladies, who each proceeded alone the best manner she could, in a predicament wherein not even the skill of Archimedes, without a single attainable point of resistance, could have rendered her assistance. On they all went, with a mincing gait, as if groping their way in the dark, some tittering, others lamenting, so that, with slipping and splashing, in despite of vigilance and timidity, certainly not less than once in every three or four steps, ill surely came of it to some of the party, either one way or another.” (Head 1937, 114-15… George Head, A Home Tour through Various Parts of the United Kingdom (London: John Murray, 1837).

Although published in 1857, W. Maxwell’s account, published in his Iona and the Ionians (which features Colin MacVean’s illustration) seems to echo Head’s and attests to the situation before the building of the new pier:

“The want of a quay, or safe landing-place, at Iona, forms a general complaint. Tourists, on disembarking from the steam vessels, have to scramble on shore, through rocks and pools, to the no small uneasiness of body, and discomposure of mind. Sundry misshapen rocks rudely piled together constitute that which, pro forma, is styled a quay! If the noble proprietor does nothing to remedy this, we are inclined to think it is the duty of the owners of the steam packets which ply on this station to erect a safe and proper landing-place for the convenience of their passengers.” (Maxwell 1857, 29-30).

A’ Chlach Mhòr

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference: NM2891524908

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 13m

Elements: G an + G clach + G mòr

Translation: ‘The great stone; the big stone’

Description:

An impressive flat-topped erratic boulder which lies to the north of Cladh an Dìseirt. From the road north of the Cathedral precinct, it is best seen from the Duchess of Argyll’s Cross. This feature at some point became identified, rightly or wrongly, with the stone mentioned in the 11th-century Irish Liber Hymnorum as Blathnat (later Moel-Blatha), q.v., as can be seen from Munro Fraser’s identification, and the Ritchie map. In the Liber Hymnorum and related accounts, this stone is described as being ‘in the church’, or perhaps better ‘in the monastic precinct’ (reclés, and see DIL s.v. reiclés for this meaning), since it is implied that it was near or in the refectory (proinntech). It seems to be Skene (Celtic Scotland vol. 2, pp. 99-100), who first argued that this field was where the original Columban monastery was, and who made the connection between this stone and the early anecdote; and this idea was further promoted by Trenholme (1909, p. 103): ‘The great tabular glacial boulder […] lies between Iomaire an Achd and the Sound […] Everything fits the stone which is still to be seen in Iona, near the spot which there are independent reasons for regarding as the site of the first monastery. The refectory which enclosed the stone, to serve as a table or sideboard, was no doubt a wood and wattle building of the old Irish kind.’

It seems slightly fantastical to imagine this boulder, the top of which is more than shoulder height, being incorporated into a building, and there is no good reason any longer to think the original monastery was where Skene, MacMillan, Trenholme et al. wished to site it. Having said this, there is no reason why, in the 11th century, the early refectory might have been imagined to have been where A’ Chlach Mhòr is, and the boulder explained as the place ‘on which division is made in the refectory’ (is furri dognither roinn isin proinntig, Bernard and Atkinson, Irish Liber Hymnorum vol. 1, 62; vol. 2, 23). And perhaps in the early medieval period there had, indeed, been a building here, associated with food preparation.

It must be these speculations, combined with the story itself, that led to the creation of the name ‘St Columba’s Table’. This seems to be first attested as a name in the Ritchies’ introduction to Iona: Past and Present (pp. 13-14), though they imply it was in common use: ‘In this same field there is the granite boulder previously mentioned, a relic of the Ice Age and called St Columba’s Table’. (This name was perhaps also prompted by the name ‘St Columba’s Pillow’ for a stone found at Cladh an Dìseirt.) The name ‘St Columba’s Table’ seems to have been revived in Canmore, displacing the Gaelic name of A’ Chlach Mhòr.

A’ Chnotag

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference: NM2763925613

Certainty: 2

Altitude: 7m

Elements: G an + G cnotag

Translation: ‘the mortar rock’

Description:

This is located on the north-west of the island, near Carraig an Daimh, but the precise feature in question is uncertain. This name presumably refers to a natural rock, possibly having been used as a mortar stone; though perhaps it only was seen as bearing a resemblance to a mortar. The word cnotag is defined in Dwelly as ‘Block of stone or wood, hollowed, out for unhusking corn; mortar’.

A’ Chorr-Sgeir a-Muigh

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV)

Classification: Island

Grid reference: NM2627225182

Certainty: 1

Altitude: m

Elements: G an + G corr + G sgeir + G a-muigh

Translation: 'the outer pointed skerry'

Description:

‘Applies to a rock in sea situate at the N. end of “Iona” about ¾ of a mile S.W. of “Carraig an Daimh” In the Ph. Of Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon’ (OS1/2/37/47)

A’ Chorr-Sgeir a-Staigh

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV)

Classification: Island

Grid reference: NM2641425101

Certainty: 1

Altitude: m

Elements: G an + G corr + G sgeir + G a-staigh

Translation: 'the inner pointed skerry'

Description:

‘Applies to a rock in sea situate between “A’ Chorr-Sgeir Muigh” and “Slochd Dùn Manamin,” In the Parish of Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon’ (OS1/2/37/47)

A’ Chorrag

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Coastal

Grid reference: NM2942026099

Certainty: 1

Altitude: m

Elements: G an + G corrag

Translation: ‘the finger’

Description:

This is a long finger-shaped rock jutting into the sea from the sand at the northern end of Tràigh Bhàn.

A’ Ghlac Mhòr

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference: NM2616122859

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 27m

Elements: G an + G glac + G mòr

Translation: ‘the big defile or gully’

Description:

The name refers to a large defile (ca. 120m in length) in the south-western part of the island, clearly visible on satellite images.

The name as represented by the Ritchie map and its descendants seems to show a dative form for the first element, glac ‘defile, hollow’, and it is noted by Dwelly that glaic was sometimes used as the nom. sg. for this word. However, three other names on the island have the nominative as glac (note in particular Glac a’ Phùbaill (q.v.), where the element is attested in this form also by Reeves and the OS). This leads us to conclude that this name should be given as A’ Ghlac Mhòr, and that the use of glaic probably reflects one of a number of places where Ritchie gives an oblique form in place of the nominative without there being a clear explanation for it.

A’ Mhachair

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Field

Grid reference: NM2681723610

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 6m

Elements: G an + G machair

Translation: ‘the machair’

Description:

The Gaelic word machair has come into both Scots and Scottish Standard English as a word in its own right, and hence this place is readily referred to in English as ‘the Machair’. There is no really adequate English translation for this term. The Dictionary of the Scottish Language gives a good definition, very well suited to Iona: ‘A stretch of low-lying land adjacent to the sand of the sea shore, covered with bent or natural grasses and used for rough grazing, common in Hebrides’ (https://dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/machair ). This seems to be a Scottish development of the early medieval Gaelic meaning of the word machaire ‘A large field or plain, sometimes used as equivalent of mag but generally of a restricted area; of level or of cleared land’ (DIL machaire). In turn, machaire is based on the root word mag ‘a plain, open stretch of land’ (DIL mag).

Although the OS Name Books give the following description: ‘An arable field south of the farm house of [Gleannbuirg ] Culbuirg Sig[nifying]: “The “plain”’ (OS1/2/37/17); in fact, the name applied to the whole stretch of short-cropped turf bordering the western seashore; from the 19th century this was common grazing for the West End crofters

In Adomnán’s seventh-century Life of Columba, he mentions the west side of the island several times, and in particular what seems to be A’ Mhachair, descriptions which indicate it was used as arable. This seems to be the area that he refers to in a number of episodes as campulus occidentalis or ‘little western plain’. This interpretation has long been accepted by scholars (see e.g. Reeves ***; Andersons **; Sharpe ***). We should not assume, however, that Adomnán is using the diminutive suffix -ulus to refer to its smallness. The use of diminutive suffixes is very much a part of his style, and it does not always mean that he is referring to something small. As this is one of the few names or nearly-names to appear in the Life it seems worth exploring the episodes here, to give a sense of the depth of the relationship between the residents of Iona and the Machair.

The arable farming practised here is evident from a story he tells (VC i.37) in which exhausted monks are returning to the monastery one evening after a day of harvesting – they are referred to as mesores ‘harvesters’. They appear to have been harvesting on the west side of the island, and are comforted by sensing Columba’s spirit at Cuul Eilne (q.v.) ‘half way between the western plain … and the monastery’.

Cuul Eilne seems to mark in Adomnán’s mental map a boundary between the western plain and the east side of the island closer to the monastic building, but A’ Mhachair is still very much part of the monastic landscape in Adomnán’s view. That is why Columba goes there and faces east to bless the whole island (VC ii.28 and iii.23) effectively making it all part of his monastic enclosure (see Márkus 2021).[1] This means that the cultivation of crops in A’ Mhachair should be seen as strictly part of the monastic life, part of the holiness of Columba’s regime, as should the building of stone walls ‘on the western plain of the island of Iona’ (in campulo occidentali Iouae insulae) mentioned in VC ii.28.

The sanctity of the western plain is confirmed by one further story in Vita Columbae relating to this area. Here Columba goes to be alone ‘on the western plain of our island’ (in occidentalem nostrae campulum insulae), and while there he climbs a little hill that overlooks the plain (supereminet campulo) to pray, and there, with his hands raised in prayer, he communes with angels (VC iii, 16).

It may be that the western plain was seen as the outermost area of sanctity in Iona – the centre being, of course, the monastic church where St Columba was buried. This notion is supported by the fact that there seems to have been a guesthouse on the west side of the island (in occidentali huius insulae parte), at least in Adomnán’s time, for that is where an exhausted crane landed and was taken to stay in a domus or hospitium, near where it landed on the western shore (VC i.48). There is no surviving archaeological evidence of such a building, but it may have been on A’ Mhachair – the most hospitable ground on the west side – where guests may have been offered lodging.

[1] See Gilbert Márkus, ‘Four blessings and a funeral: Adomnán’s theological map of Iona’, The Innes Review 72 (2021), 1-26.

A’ Mholldrunach

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Coastal

Grid reference: NM2792225814

Certainty: 1

Altitude: m

Elements: G an + G mol or G mol + G dòrnach

Translation: ? ‘the clamorous pebbly beach’

Description:

This difficult name belongs to a beach entirely covered with pebbles in the north of Iona. The meaning given by Munro Fraser, ‘the pebbly beach’, seems undoubtedly correct, but the exact way the elements of the name work together is less clear. The name is given by Dugald MacArthur as ‘The Molldrunach’ (Tobar an Dualchais ID84012 part 1, 42:00).

Both the potential main elements of the name could on their own be words for a beach: mol ‘shingly beach; shingle’ and dòrnach, not attested as a common noun, but well-known in place-names (such as Dornoch) meaning ‘pebbly place’. However, taken together this seems an odd combination. It seems certain that this is a close compound, the first element being the specific, modifying the second. This is shown by the stress in the name, which is on mol(l)- ), which has probably led to the metathesis and shortening of the unstressed first syllable of dòrnach, to -drunach. However, ‘the shingly-beach-pebbly-place’ seems an odd name, if that is what we are looking at. It may be, in that case, that the first element is not mol ‘shingly beach’, but the adjective mol ‘loud, clamorous’ (Dwelly; cf. DIL mol 2), giving the name the meaning ‘the clamorous pebbly place’, presumably referring to the noise of the water through the stones, or the sound made when walking on the surface.

The name is, however, consistently spelled with a -ll. The appropriateness of mol, in either meaning, encourages us to think that this is just a spelling anomaly, and that the name actually represents a name which would originally have been written *A’ Mhol-Dòrnach. However, it is worth leaving the door open for the -ll representing the actual spelling of the first element; moll ‘chaff, dust’ is a word, though the meaning would then be hard to discern.

Because of all these uncertainties, it has been thought best to retain the spelling that is consistently attested since Reeves.

Achabhaich

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Settlement

Grid reference: NM2870625135

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 28m

Elements: en Achadh a’ Bhàthaich

Translation: This adapts an existing name of a landscape feature: see entry for Achadh a' Bhàthaich

Description:

As with other crofts on the island, this one has taken its name from a topographical feature, analysed under the existing name Achadh a’ Bhàthaich (q.v.). Settlements by and large were given anglicised spellings by the Ordnance Survey and other authorities, and these seem often to have been employed as the official name by the residents of the crofts / houses in question, even where they were Gaelic speakers.

The name means ‘field of the byre’, and the field after which it is named is on the left going north, where the main house is; a byre once stood against the rock on the corner just at a bend in the road. One local belief was that this had been the monastery byre; more likely it was for the cattle of 18th century tacksman John Maclean who, in the pre-crofting era, held most of the north-east land. The tradition of the byre having belonged to the monks is mentioned by Dugald MacArthur who similarly concludes that this more likely belonged to John Maclean (TAD ID 84012 part 1 8:02). For further discussion of the improvements undertaken by John Maclean in the 18th century, see MacArthur (1990, p. 12).

OS Name Books description: ‘A farmsteading about half a mile north of the Cathedral. Property of His Grace the Duke of Argyll’

Achadh a’ Bhàthaich †

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Field

Grid reference: NM2887225123

Certainty: 2

Altitude: 17m

Elements: G achadh + G an + G bàthach

Translation: ‘field of the byre’

Description:

For early forms, and discussion of the location, see Achabhaich.

This is the topographical feature which gave its name to the croft of Achabhaich. Achadh ‘field’ is a very common place-name element across Scotland, particularly in the east and south-west, where it came to mean, essentially ‘farm’. Many such names elsewhere in Scotland must have been coined before the 12th century. However, although we are dealing with a croft in this case on Iona, the process of Achadh a’ Bhàthaich going from a field name to a settlement name is evidently a late one, dating from the establishment of the crofts on the island.

Àird an Dòbhrain

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Coastal

Grid reference: NM2653623406

Certainty: 1

Altitude: m

Elements: G àird + G an + G dòbhran

Translation: ‘point/promontory of the otter’

Description:

A rocky point on the shoreline of the southern part of the Machair (A’ Mhachair).

The specific element is G dòbhran, m. ‘otter’ (Dwelly: ‘Freshwater otter Mustela lutra’ s.v. dobhran, MacEachen: dòbhran, also biast-dubh and cù-donn), perhaps indicating a spot frequented by otters.

It is interesting to note that there is a potential connection between St Oran and the otter in Gaelic folklore. In Fr Allan Macdonald’s version of the story in which St Oran is buried alive so that the church on Iona could be built he is named Dobhran, the brother of St Columba (reproduced in The Celtic Review vol. 5, pp. 107-109. See Sharpe 2012, pp. 206-10 for other versions of the story; also see Márkus 2022). As Clancy (2018 s.v. ‘Oran, Odhran’) has argued: ‘Consider the nature of the key anecdote about Odhran as well, with all its liminal imagery of being submerged, and hesitating before making landfall. Is that half-land/half-water image also related to the character’s rechristening in modern Gaelic folklore as Dobhran (“otter”)?’.

Àird Annraidh

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference: NM2913325915

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 9m

Àird nan Taighean

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference: NM2713823546

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 15m

Elements: G àird + G an + G taigh

Translation: ‘height of the houses’

Description:

A sloping hill to the south of the croft of Shian. Although there are no houses there, the name has preserved a tradition of their presence; Dugald MacArthur (TAD recording part I, 29.40), speaking in 1965, noted that ‘there were houses up there at one time’. It is likely that in the 19th century many of the crofts on the island had more houses and families on them than today.

Although the name forms consistently present both àrd and tighean, since there is little doubt about the meaning the name as given here provides the standard orthography for both elements (whose orthography is notably variable prior to standardisation). Dugald MacArthur in the 1965 recording mentioned above clearly says taighean.

OS Name Book entry: ‘A hill a short distance south west of Shian Sig; “Height of the houses”’ (OS1/2/37/22)

Allt a’ Chaorainn

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference: NM2722222210

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 26m

Elements: G allt + G an + G caorann

Translation: ‘cliff or gully of the rowan-tree’

Description:

The name seems to describe a precipitous gully in the vicinity of Druim Dhùghaill. The generic element in the name, allt, is somewhat problematic. In Scottish Gaelic, allt almost always refers to a burn or stream, often one flowing through a gully, but not usually the gully itself. There is no such burn at this site, at least not in normal weather conditions. Equally, the translation given by Munro Fraser has allt as ‘cliff’, implying that was how it was understood at the time. Now, notably, this follows Reeves’s translation, and in Early Irish, allt meant ‘height, cliff’ (dil.ie/3017). This later developed a secondary meaning, ‘downward drop, valley, abyss’, which then gave Modern Irish ailt ‘a ravine’. Scottish Gaelic seems to have developed further, and the term became attached to the burn present in such steep-sided ravines, and thence expanded to other mountain streams and the like. However, ‘cliff’ is not normally a meaning for allt in Scottish Gaelic, and so it may be that this is a misinterpretation of Reeves which has found its way into the lists. While allt generally does not mean ‘ravine’ in Scottish Gaelic either, it seems less of a stretch, and indeed, better suits the feature which seems to have been being described. However, it does seem to imply a perhaps conservative dialectal usage of the term on the island. It does not help that this would appear to be the only place name in allt on Iona, and so there is no further assistance in testing this idea.

Rowan trees are frequent inhabitants of steep sided gullies.

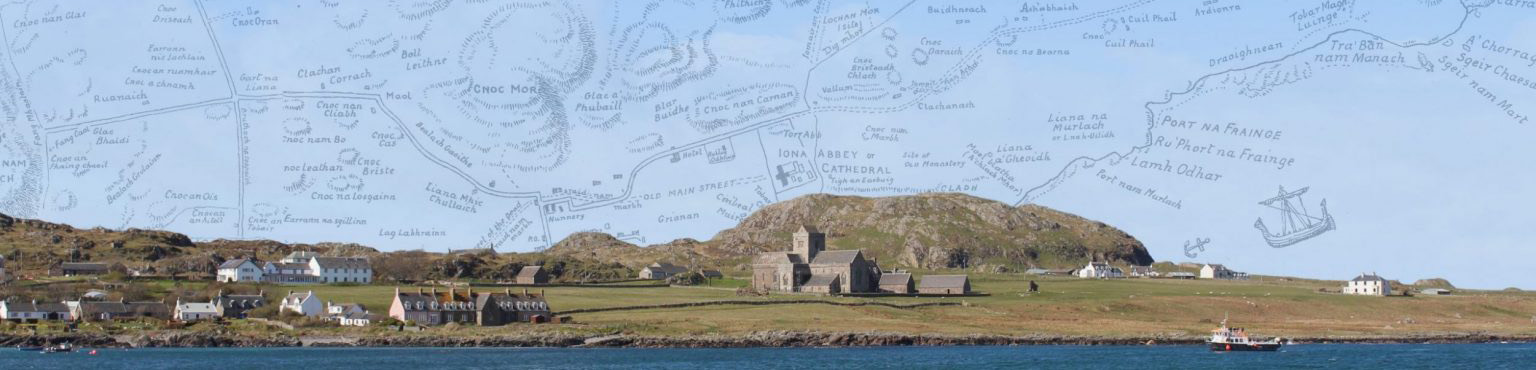

Am Baile Mòr

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Settlement

Grid reference: NM2842924092

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 18m

Elements: G an + G baile + G mòr

Translation: 'the big town'

Description:

The main settlement on Iona in which most of the population resides. It is likely that the population has been concentrated here since the medieval period (Argyll 4, p. 8). It was described in the OS Name Books in the 19th century as follows:

The principal collection of houses in the island of Iona, consisting of a single straight street on the shore of the sound, and including under the name, the ruins of the Cathedral Church and Nunnery. It contains two Hotels and a beer-house - there are no spirit licenses granted to the island - an Established Church and School. There is also a Free Church on the island but it is more properly situated in Sligneach, although only a short distance from the village. Property of His Grace the Duke of Argyll.

Although early forms before the 19th century all record the name without the definite article, the forms given by Ritchie and D. Munro Fraser provide a basis for including it in the headname. It is likely that in a Gaelic-speaking context the definite article would have been used, and we have therefore decided to include it.

Am Bealach Mòr

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference: NM2553422285

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 23m

Elements: G an + G bealach + G mòr

Translation: ‘the big pass / gap’

Description:

This name seems to describe the large defile between Aoineadh nan Sruth and Druim an Aoinidh.

Am Bruthas

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV)

Classification: Coastal

Grid reference: NM2795823113

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 5m

An Àilean Bhàn

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Field

Grid reference: NM2800423309

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 6m

Elements: G an + G àilean + G bàn

Translation: ‘the white/fair meadow’

Description:

A meadow located next to Traighmor cottage near the eastern coastline of Iona. This topographical name was transferred to the name of the nearby croft, one of the thirty crofts created in 1802, known by the same name (for which see entry), which later became known as Greenbank.

G àilean is typically a masculine noun, and we would therefore expect An t-Àilean Bàn, rather than An Àilean Bhàn. In a Mull context its masculine form is well-attested in place-names and song (ACW ref). Alternatively, the attested form of the name may be the result of back formation from an oblique dative form. However, it seems more likely that àilean is used as a feminine noun in this context, possibly reflecting local Iona usage.

It is possible that the name refers to the colour of the feature, but in the context of a meadow or field it seems more likely that it references its grazing quality. As noted by Simon Taylor (PNF 5, p. 530), words denoting a fair colour (Sc white, G fionn) can be used in this context and white is defined in SND as follows: ‘of arable land: fallow, unploughed, as stubble land, old pasture, etc. (Cai. 1974); “of grass or arable land among surrounding moss” (Gall. 1887 H. E. Maxwell Topogr. Gall. 308); of hill-land: covered with coarse bent or natural grass instead of heather, bracken or scrub (Ags., Slg., Bwk., Ayr., sm.Sc. 1974).’

The name was well known to Calum Cameron, crofter at Traighmor right next to An Àilean Bhàn; when overhearing his elderly neighbour talking aloud on occasion: ‘If I’m alive next spring, and by God I will be, I’m going to plough the Ailean Bhàn’ (recorded 1985).

An Àilean Bhàn

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Settlement

Grid reference: NM2808723330

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 4m

Translation: This adapts an existing name of a landscape feature: see entry for An Àilean Bhàn

An Àird

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference: NM2659621739

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 25m

Elements: G an + G àird

Translation: ‘the height’

Description:

An area of high ground located at the south-eastern end of the island. Note that there is another An Àird only recorded on Reeves’ map just north of the Cathedral precinct, for which see entry.

OS Name Books description: ‘A rocky ridge near the coast, on the north side of Rudha na Carraig-géire, and about a quarter of a mile south east of Buaile Staoineig. Sig: “The Height”’ (OS1/2/77/139).

An Àird †

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference: NM2872724663

Certainty: 2

Altitude: 19m

Elements: G an + G àird

Translation: ‘(the) height’

Description:

This obsolete name, represented only on Reeves’ map and list, and seemingly present in Munro Fraser’s appendix but not on the Ritchie map itself, seems to have referred to the higher ground north of the Cathedral precinct, heading towards Clachanach. Because it is only on Reeves’ map, the exact location is somewhat uncertain. It may be referenced in the name Rubha na h-Àirde (q.v.).

Though the only early forms we have do not represent the name with a definite article, on the premise that simplex nouns generally are preceded by the definite article in modern Gaelic, and that the article seems to be shown before this name in Rubha na h-Àirde, we have supplied it in the headname. Note however that there is a second place named An Àird in the south of the island.

An Àth

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Other

Grid reference: NM2864825176

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 33m

Elements: G an + G àth

Translation: ‘the kiln’

Description:

The remains of a drying place for grain near the foot of Dùn Ì, known locally as ‘the Àtha’.

An Curachan

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Antiquity, Ecclesiastical, Relief

Grid reference: NM2633621775

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 6m

Elements: G an + G curachan

Translation: 'the small curach or coracle'

Description:

A grassy, boat-shaped mound located at Port a’ Churaich ‘port of the coracle’. According to tradition, both the port and mound are linked with the arrival of St Columba on Iona, the latter supposedly representing the boat the saint arrived in. An Curachan is frequently mentioned in this context in antiquarian accounts, but as noted by Ian Fisher, excavations in the late 19th century ‘revealed no evidence of artificial origin’ and the mound is likely a natural feature (Argyll vol 4, p. 258; also see Canmore ID 21634).

It is noteworthy that Port a’ Churaich is generally recorded with G curach rather than its diminutive form found in An Curachan (but note that Carmichael gives it as An Curach). There is, however, some evidence for the use of curachan in the name for the port. MacCulloch (1819) gives the name as Port na Curachan and Scott’s 1830 painting of the port is named Port na Curachan. Although there are several difficulties in tackling the gender of the specific element in Port a’ Churaich, we would expect G curachan to be masculine, so this headname is relatively straightforward. See entry for Port a’ Churaich for further discussion.

Several early modern accounts mention the mound in discussions of Port a’ Churaich, but before Reeves in the mid-19th century they do not specifically name it. The earliest account mentioning the feature seems to be the Wodrow letter dated to 1701 which notes that:

The length of this Curachan or ship is obvious to any who goes to the place, it being marked up att the head of the harbour upon the grass, between two litle pillars there is three score of foots in lenth, which was the exact length of the Curachan or ship.

The anonymous account from 1771 similarly states that:

The natives of the place affirm that Columba landed here first; and they even pretend to ascertain the dimensions of his Curach. There is a cavity dug in the ground, resembling somewhat the form of a boat, the length of which is determined by two massy stones erected at each end. Here it is affirmed Columba’s Curach lay; but then these dimensions are so large as to exceed all probability.

Although these early descriptions clearly refer to the site which would eventually be called An Curachan, they do not appear to be name forms per se and have therefore not been included in the early forms.

The tradition St Columba’s arrival on Iona has also inspired the name The Coracle, the journal published by The Iona Community. The first issue (1938) introduces the publication:

As one day we stood on the slipway of Iona—there is no pier and everything from a needle to an anchor has to be manhandled on to the shore-answering further innumerable questions from mystified visitors, the brilliant idea struck us that we might answer everyone at one fell swoop by launching just such a sn1all boat as St. Columba used to carry his messages to the mainland—a Coracle. This led to sound sleep—for at least a fortnight-it was quite simple—“The Coracle” would sail into a thousand letterboxes and honour would be satisfied.

The outline of the mound is faintly visible, but can be seen more clearly on LiDAR data (see image).

An Eaglais Dhubh | Nunnery

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Antiquity, Ecclesiastical

Grid reference: NM2848024099

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 14m

Elements: G an + G eaglais + G dubh

Translation: 'the black church' (possibly in reference to the vestments of the nuns)

Description:

Given that the stone used to build the nunnery gives a rather light and rosy-pink impression, it is hard to imagine that the dubh of the name refers to the colour of the buildings. It is more likely, as suggested in the 1771 entry, that the colour-reference was originally to the habits of the Augustinian nuns who lived here from perhaps the late twelfth century. That account refers to the nunnery as Manastear na’n Caileach dubh (modern Gaelic Mainistir nan Cailleach Dhubha), ‘monastery of the black nuns’. The author comments on what he regards as the strangeness of the name: ‘It is a little striking that the word Caileach [sic] is a term of contumely or reproach, alluding to a shabby old woman. By this we may conjecture what ideas the inhabitants of Mull had of convents and the religious ladies.’ This is misleading, however. Far from being ‘a term of contumely or reproach’, the word cailleach refers to the wearing of a veil, caille—something which nuns wore, of course, as well as old women. There is nothing ‘shabby’ about it.

It seems that in this place-name the epithet dubh ‘black’ has been transferred from the habits of the very respectable nuns to the nunnery or church itself. This a recognised feature of naming practice in the Gaelic-speaking world. It is probably the explanation for the naming of a church building in Derry as the ‘little black church’ in the twelfth-century Preface to the Altus Prosator, a hymn which he is said to have written ‘in Cellula Nigra .i. isin dúib-recles i nDoire Choluim Cille (‘in the little black church in Derry Columcille’) (ILH i, 62 [ii, 23]). This dubreiclés was burned in 1166, according to the Annals of Ulster, and in 1173 Muiredach Ua Cobhthaigh, bishop of Cenél nEogain is recorded having ‘breathed forth his spirit in the Dubreicles of Colum Cille in Derry’ (AU Muiredach h-Ua Cobhthaigh, espoc Ceneoil Eogain & Tuaisceirt Erenn uile … ro fhaidh a spirut dochum nime i n-Dubreicles Coluim Cille i n-Daire). As Derry was probably already an Augustinian community by this time, it is likely that the dubh in this name referred to their black habit. Likewise, Monasternagalliaghduff (Mainistir nan Cailleach Dhubha in Scottish Gaelic) in County Limerick is named after its Augustinian nuns; while Templenagalliaghdoo by Lough Conn, Co. Mayo was also a community of black nuns, Augustinians. Further examples references to the epithet dubh can be found in other Hebridean place-names; in particular see Taigh nan Cailleachan-Dubha on Lewis (Cox 2022, 921-24).

Cistercians, in their white, or off-white, habits gave their name to An Mhainistir Liath ‘the grey abbey’ on the Ards Peninsula, east of Belfast. There is a Black Abbey, or An Mhainistir Dhubh in Co. Limerick, which was an Augustinian community. Blackness was also a mark of Dominicans—they wear a black cappa over their white habit—and this gave the name to An Mhainistir Dhubh in Kilkenny, Black Abbey, where they established a priory in 1235.

For a description of the nunnery buildings, see Argyll 4, 152-79. The seventeenth-century Book of Clanranald states that the first prioress of the nunnery was the sister of Raghnall (Reginald) son of Somerled, Bethoc or Beatrice. She was commemorated on a stone that survived as late as the nineteenth century, which was recorded by Martin Martin as being inscribed Behag nijn Sorle vic Il vrid Priorissa (‘Bethoc daughter of Somhairle son of Gille-Bhrighde, prioress’) (Martin 1703, 263). Whether Bethoc was truly the first leader of this community or not is uncertain. Given that her father died in 1164, it is quite plausible that she was a nun here in the late twelfth century, or early thirteenth, and this would fit with the estimated time of the construction of the present nunnery buildings. But it is worth considering the possibility that these buildings were erected as part of the reform of an existing community of women who had recently adopted the Augustinian rule but which had been in existence for some time before that. Bethoc may simply have been the first prioress of the Augustinian version of the community. For evidence of women religious having been on Iona long before Bethoc’s lifetime, see entries on An Eala, Cladh nan Druineach and Teampall Rònain. It is a recognised feature of early medieval Gaelic monastic landscapes that important male monasteries had ‘satellite’ communities of women outside their main enclosures: examples may be found at Clonmacnoise, Finglas, Glendalough, Armagh, Lemanaghan.

Note that mainistir, a loan-word from the Latin neuter noun monasterium, is feminine in OG (DIL) and modern Irish, but masculine in Scottish Gaelic (Dwelly).

An Eaglais Mhòr | St Mary’s Abbey

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Antiquity, Ecclesiastical

Grid reference: NM2868024519

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 18m

Elements: G an + G eaglais + G mòr

Translation: 'the great church'

Description:

The name is self explanatory. As it is by far the largest of the several medieval churches on the island, the epithet mòr may relate both to its size and to its importance as the principal place of prayer in the medieval monastic landscape.

It has had other names too: St Mary’s Cathedral, The Cathedral (usually the name used locally in and English-speaking context), St Mary’s Abbey, An Eaglais Àrd (‘the high church’).

It is highly likely that the present late medieval building stands on the site of the early medieval church. This earlier building is referred to by Adomnán in his Vita Columbae variously as ecclesia (VC i, 8; i, 22; ii, 40; ii, 42; iii, 17; iii, 19; iii, 23) and oratorium ‘prayer house’ (VC i, 8; i, 32; ii, 40; ii, 42; iii, 19), sacra domus ‘sacred house’ (iii, 19). It is worth noting that in several of the chapters when Adomnán mentions the ecclesia the same building is referred to again in the same chapter as an oratorium. This seems to be a stylistic quirk in Adomnán’s writing: if you mention the same place twice in succession, you should if possible use two different terms for it. He has a penchant for variation rather than repetition. For a detailed description of this church and its features, see Argyll 4, 49-114.

An Eala

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Antiquity, Ecclesiastical

Grid reference: NM2846123870

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 3m

Elements: G an + G eala

Translation: ‘the mound’

Description:

This name represents Gaelic ealadh (in Dwelly’s dictionary eala is offered as the principal form, but ealadh is also given as a ‘provincial’ form), but some confusion has surrounded it in the past. In the form An Eala, as given on OS maps, the name was once thought to represent G eala ‘swan’, as suggested by MacDonald of Knock (1776), and again by Graham (1850) and the OS Name Books (OS1/2/37/26) which refer to it as ‘A small hillock at Port mam Mairtir on which the coffins were set after being taken from the boat, and while the funeral processions were being arranged for Reilig Oran. A street led from this point to St. Oran’s Chapel. Meaning “The Swan”’. Watson is clearly correct, however, in offering its true Gaelic form as An Ealadh (1926, 260). For a discussion of the less convincing interpretations of the name, see Sharpe, ‘Iona in 1771’, 224-226.]

The Gaelic word ealadh as cited by Watson appears in an alarming variety of written forms. DIL offers, under the head-form ailad, forms such as aulad, ilad, elad, ulad, ilaidh, elaith, ulaidh, ulaid, hullta, ailaidh, elaid, aulaid, iolaidh, ilaidh, uladha, uladh, ulltaib, ula, ila, eala, uladh, ultha (dil.ie/961). The modern Irish spelling of the word is ula (Niall Ó Dónaill, Foclóir Gaeilge-Béarla). Interestingly, this Gaelic word may also have been borrowed into Latin as ola, as found in the Vita Sancti Cainnechi, in a story where a king says to the saint, “O man with a staff, don’t speak idle words, for they will not deliver you, for today your soul will perish unless by the power of your God you cause one of the swans which are now swimming on that loch to come in this hour in swift flight and land on my ola, and another one to land on your ola.’ (Gilbert Márkus, trans., The Life of St Cainnech of Aghaboe, published on-line, 2018[1]). The translator had difficulty in making sense of this passage in 2018, and translated ola (with much hesitation) as ‘shoulder’. In retrospect, he now considers that he should perhaps have considered it as a loan-word into Latin from Gaelic ealadh.

DIL offers ‘tomb, sepulchre, burial cairn’ as the original meaning of ailad, but shows how its meaning expanded to include ‘a calvary or charnel-house, a cairn, a heap or pile of bones in a church-yard’ and ‘a penitential station’. This last term refers not to the original purpose of the ailad but to its subequent use as a place of ritual. It is possible that the term ailad was sometimes applied to stone-built ritual sites which had not actual burial present. As we shall see, the archaeological and historical evidence shows that An Eala on Iona was both a burial place and a ritual focus.

According to RCAHMS report on An Eala, then ‘a low turf-covered mound’, the presence of human burials first reported in the eighteenth century was confirmed in 1961, when two human skeletons in stone-lined long cists were uncovered during pipe-laying operations. Further excavations in 1969 revealed three other long cist burials, and numerous others, all covered by wind-blown sand. ‘It was possible to identify at least forty individuals, with a marked preponderance of females whose average age at death was about forty. Of the eight females whose skeletal remains permitted a determination to be made, none had borne children. It was also noted that neither men nor women exhibited evidence of the hard-manual labour to be expected among a peasant community and none had died by violence. From these conclusions the burials may tentatively be associated with a community of celibate females’ (Argyll 4, 244). Subsequently, the Crick Institute has re-examined bone from fifteen individuals at the site looking for ancient DA. Fourteen of them were identified as female. Bone from one of these individuals was radiocarbon-dated to AD 668-774,[2] and it is hoped that carbon-dating will be applied to further samples shortly (Adrián Maldonado, pers. comm.). Further dating evidence from the area emerges from an excavation by Derek Alexander (National Trust for Scotland) in 2020, when a series of ‘rectangular spade-dug pits [which] looked like they might have been graves’ were found, along with two Viking-age pins. Interestingly, these features were cut into a layer of charcoal dated AD 428 x 600, which coincides with the period when the monastery was founded on the island (D. Alexander, ‘Beyond the Boundary, blog [19 August 2020], https://www.nts.org.uk/stories/beyond-the-boundary).

The references given in the early forms above give some indication of the ritual use of An Eala in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Mairghread Nighean Lachlainn’s poem (1717) refers to An Ealadh as a place where a body would be brought to shore for burial, a practice also referred to in the entry for 1771, and in MacDonald’s reference of 1776 where the sites is referred to as ‘a Rock called the Swan’. This is the earliest reference to there being a particular rock, or rocky construction perhaps, identified with An Eala, rather than simply a burial site covered by a mound of wind-blown sand. Carmichael in 1928 referred to An Eala as ‘a platform … in the form of an altar’, also hinting at something constructed, perhaps of stone.

Reeves (1857) referred to ritual activity there: ‘funeral parties on landing were formerly in the habit of laying the remains upon this mound, while they thrice performed a deisiol or right-wise circuit around the spot,’ while in 1928 Carmichael referred to a similar, though not identical rite, in which the body itself was carried three times round An Eala. The difference in the description may suggest that Carmichael was not dependent on Reeves for his information.

Although the earliest form of the place-name is in a poem of 1717 (see early forms above), we do have a much earlier reference to the place. In 1532 Manus Ó Domhnall, chief of Tír Conaill in Ireland, completed his Beatha Colaim Chille or ‘Life of Columba’. In this work he tells a new version of a story which he has found in Adomnán’s Vita Columbae (I, 33), where an old Pict called Artbranan comes to Skye and is baptised by Columba. But Manus transfers the story to Iona where Colum Cille and his monks are praying on the seashore when a boat comes in and an old man is brought ashore. Colum Cille preaches to him, blesses and baptises him, and the old man dies and his buried there. ‘And the monks that were with Colum Cille at the time made an ula in that place in memory of that story, and it remains there since then’ (Acus dorindetar na manaich do bi fare C. C. an uair sin ula ‘san inadh sin a cuimhniughadh an sceoil sin, acus mairidh sí and ó sin ille) (A. O’Kelleher and G. Schoepperle, Betha Colaim Chille: Life of Colum Cille (Urbana, Illinois, 1918), 262). The word ula here is clearly being used as a common noun, not as a place-name, but it must refer to our An Eala. It is interesting, given the word dorindetar, that O’Donnell sees it as something that has been constructed. Did O’Donnell know about this ritual monument on the shore of Iona, and carefully write it into his Life?

Interestingly, there is another story in O’Donnell’s Life of Columba in which this kind of monument plays a role. It occurs when Pope Gregory tells Columba to choose which of his churches he wants to assign as a place of pilgrimage, so that any pilgrim who goes there should have the same grace as he would receive from making a pilgrimage to Rome. Columba chose Derry for this privilege, and described the route the pilgrims should take on arrival: .i. ó an ulaidh ata ag port na long ‘sa cend toir don baili, connige an t-impódh dessiul ata ‘sa cend tíar de (‘that is, from the uladh that is at the harbour of the ships in the east and of the place, to the righthandwise/sunwise turn (dessiul) at its west end’) (O’Kelleher and Schoepperle, 212). We may note that both An Eala on Iona and the uladh at Derry are at the landing-place of ships, both are associated with the arrival of pilgrims or visitors, and both are associated (directly or indirectly) with the ritual sunwise turn.

For discussion of another ealadh which formed part of a ritual landscape of procession and deiseil or sunwise movement and prayer, see the discussion of Ollamurray (Ulaidh Mhuire ‘the ealadh of Mary’) on Inishmurray, which is a roughly square rubble cairn or leacht built inside a small four-sided drystone enclosure (Jerry O’Sullivan and Tomás Ó Carragain, Inishmurray: Monks and Pilgrims in an Atlantic Landscape (Cork, 2008), 298-303; Tomás Ó Carragáin, ‘The Saint and the Sacred Centre: the early medieval pilgrimage landscape of Inishmurray’, in Nancy Edwards (ed.), The Archaeology of the Early Medieval Celtic Churches (London, 2009), 207-226).

[1] https://uistsaints.co.uk/saints/coinneach/

[2] Skull 21/I (adult female): OxA-43439, 1288 ± 17, AD 668-774.

An Geodha Dearg

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Coastal

Grid reference: NM2604922973

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 1m

Elements: G an + G geodha + G dearg

Translation: ‘The red cove or inlet’

Description:

The feature in question seems to refer a small cove located at the south-western side of Iona between the rocks jutting out into the sea, just north of St Martin’s Caves.

The specific element G dearg perhaps most likely refers to the colour of the sea rocks surrounding the cove in question. Rock with a distinctly red colour can be found along the south-western coast of the island (see image showing the cliffs near the Spouting Cave, just north of An Geodha Dearg).

Although G ruadh appears in several place-names, this is the only Iona name which contains G dearg. For comparison, there is a Geodha Dearg in Sutherland (NC506682) which undoubtedly takes its name from the distinctly red rockface surrounding the cove.

An Goirtean Dubh

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Field

Grid reference: NM2639722437

Certainty: 2

Altitude: 46m

Elements: G an + G goirtean + G dubh

Translation: ‘the black cornfield’

Description:

Though much of the south end of Iona is moorland, there are pockets – and then larger areas – of greener ground once you pass the loch. This was once Nunnery land, its boundary marked by the stone wall Gàrradh Dubh Staonaig (for which see entry). Local belief was that the dubh related to the dark clothing of the Nuns. Could this goirtean, close by that boundary, be named dubh for the same reason?

An Nòs

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV)

Classification: Coastal

Grid reference: NM2802123145

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 3m

An t-Ìochdar

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference:

Certainty: 1

Altitude: m

Elements: G an + G ìochdar

Translation: 'the lower part'

An Uirigh Riabhach

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV)

Classification: Coastal

Grid reference: NM2549021966

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 3m

Elements: G an + G uirigh + G riabhach

Translation: 'the brindled ledge'

Aodann an Lochain

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference: NM2683023114

Certainty: 2

Altitude: 21m

Elements: G aodann + G an + G lochan

Translation: '(hill-)face of the small loch'

Description:

This name describes the stretch of high ground, with a deep gully to the east, looking down onto Lochan Mhic an Aoig directly to the north-west.

Aodann an Taoibh Àird

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference: NM2772922900

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 26m

Elements: G aodann + G an + G taobh + G àrd

Translation: '(hill-)face of the high side'

Aoineadh an Taghain

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference: NM2580721944

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 18m

Elements: G aoineadh + G an + G taghan

Translation: 'the steep promontory/precipice of the pine marten'

Aoineadh Mòr

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference: NM2730022218

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 24m

Elements: G aoineadh + G mòr

Translation: 'the big steep promontory'

Aoineadh nan Sruth

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV)

Classification: Relief

Grid reference: NM2535722517

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 11m

Elements: G aoineadh + G an + G sruth

Translation: 'steep promontory/precipice of the currents'

Description:

‘Applies to a cliff situate at the S.W. end of “Iona” between Port Aoineadh nan Sruth, and “Port Beul-mhoir.” Sig; Precipice of the currents’ (OS1/2/77/148)

Ardionra

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV)

Classification: Settlement

Grid reference: NM2897225577

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 18m

Elements: en Àird Annraidh

Translation: This adapts an existing name of a landscape feature: see entry for Àird Annraidh

Argyll Hotel

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV)

Classification: Settlement

Grid reference: NM2858124113

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 6m

Elements: en Argyll + SSE hotel

Description:

‘A licensed beer house in the village of Baile Mòr. It is two stories in height, has ordinary accommodation for travellers, but no stabling attached.’ (OS1/2/37/28)

Athaluim

Kilfinichen & Kilvickeon (KKV), Iona (IOX)

Classification: Other

Grid reference: NM2809623272

Certainty: 1

Altitude: 2m