Thomas Clancy writes:

Nollaig chridheil dhuibh uile bho sgioba ‘Ainm-thìr Ìdhe’!

Happy Christmas to you all from the Iona’s Namescape team!

At this season, one image on Iona stands out, and that is the Virgin and Child depicted in the roundel on St Martin’s Cross, with angels’ wings arched over them. Situated at the juncture of the cross, it encapsulates at once the notion of Jesus as the incarnation, and the crucified Christ. Flanked by angels, and protected in the roundel’s circuit-wall, outside on the arms the Virgin and Child seem beset by beasts, an idea emphasised by the image of Daniel in the lion’s den below, which echoes the image of Christ, as various art historians have discussed. (Another similar depiction can be found on St Oran’s Cross.)

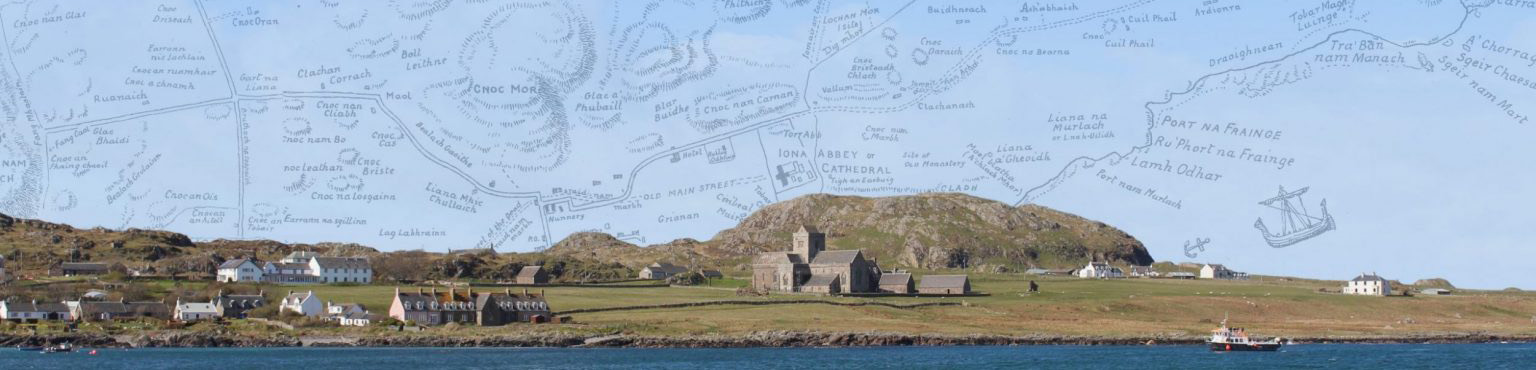

The Virgin Mary is also represented in two place-names on Iona. One is Caibeal Mhuire, in English, St Mary’s Chapel (NM2869324422), which appears from the end of the 18th century under names similar to this. This ruined building lies to the south of the Cathedral, indeed, within sight of St Martin’s Cross as one gazes at the side with the Virgin and Child image.

It looks likely to have been built in the 13th century; however, traces of a road going past it might suggest earlier origins [see Canmore]. As far as the name goes, it cannot be certain when this was attached to it, though speculation has linked it with the foundation of the Benedictine monastery in the early 13th century.[1] Mentioned a bit earlier is the presence of the Virgin Mary in the name of the Cathedral. Martin Martin in 1703 is our earliest source for this as “St Mary’s Church”; we can’t be certain that later mentions of this are independent of his account.[2] However, given the views of the Prostestant reformation, which took hold in Scotland from 1560, it seems unlikely that either name was coined later than that date; so both of these commemorations of Mary are almost certainly medieval. But how old?

There is a general assumption when it comes to universal and biblical saints like Mary that their veneration (and hence presence in place-names) is a later phenomenon, belonging to the period of church reform in the 12th century and the like. And certainly we have ample evidence of churches in the 12th and 13th centuries being renamed for the Virgin Mary, or having her name added alongside another local saint in joint dedications.[3] And there is good sculptural evidence for the continued veneration of Mary through the later Middle ages on Iona, for instance on the grave-slab of Prioress Anna MacLean (see here). So there is nothing against thinking of Mary’s name having entered the place-name repertoire of Iona in the period after 1200; indeed, maybe this is the most logical conclusion.

On the other hand, it is worth stressing that Iona is one of the places where we find a fully developed cult of the Virgin Mary from very early on. We can see it in the work of Adomnán, ninth abbot of Iona (†704), who tells us a miracle story relating to an image of Mary in Constantinople in his De Locis Sanctis, ‘On the Holy Places’.[4] Mary was also invoked as a patron and prompt for his Law of the Innocents, passed by assembled clerics and kings from Ireland and northern Britain in 697.[5] That devotion is also found on early sculpture from Iona, on St Martin’s Cross for instance, as mentioned; and further afield at Kildalton on Islay.[6] And churches elsewhere in the Hebrides dedicated to Mary show signs of earlier use.[7]

As a result of this, it is quite possible that a church or subsidiary chapel on the island of Iona might have been dedicated to the Virgin Mary at an early date. We don’t fully understand how separate individual church buildings in early medieval Gaelic monasteries functioned—were they for separate groups of people, or separate events, or certain types of prayer? But we shouldn’t rule out the potential for Caibeal Mhuire, later medieval building though it is, to reflect something earlier.

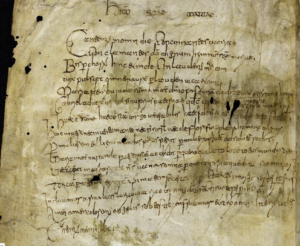

For a flavour of early devotion to Mary, and a sense of how she was seen in the early period of Hebridean Christianity, the Latin hymn by Cú Chuimne, a monk of Iona, gives us some sense.[8] It can be found in the Irish Liber Hymnorum of the 11th century, but also in another, continental manuscript of the late 8th or early 9th century, which you can examine here: https://digital.blb-karlsruhe.de/blbhs/Handschriften/content/pageview/247895

Mary of the Tribe of Judah, / Mother of the Most High Lord, /gave fitting care /to languishing mankind.

Gabriel first brought the Word / from the Father’s bosom /which was conceived and received / in the Mother’s womb. …

By a woman and a tree / the world first perished; / by the power of a woman / it has returned to salvation.

Mary, amazing mother, / gave birth to her Father, / through whom the whole wide world, / washed by water, has believed. …

Let us call on the name of Christ, / below the angel witnesses, / that we may delight and be inscribed / in letters in the heavens.

Listen to a modern setting of the hymn, Patrick O’Shea’s composition from 2014.

And here is the whole hymn, as edited and translated by Gilbert Márkus:

| 1. Cantemus in omne die concinentes varie conclamantes deo dignum ymnum sanctae Mariæ 2. Bis per chorum hinc et inde 3. Maria de tribu Iudæ 4. Gabriel aduexeit verbum 5. Haec est summa haec est sancta 6. Huic matri nec inventa 7. Per mulierem et lignum 8. Maria mater miranda 9. Haec concepit margaretam 10. Tunicam per totum textam 11. Induamus arma lucis 12. Amen Amen adiuramus 13. Christi nomen invocemus |

Let us sing every day. In two-fold chorus, from side to side, Mary of the Tribe of Judah, Gabriel first brought the Word She is the most high, she the holy None has been found, before or since, By a woman and a tree Mary, amazing mother, She conceived the pearl The mother of Christ had made Let us put on the armour of light, Truly, truly, we implore, Let us call on the name of Christ,

|

[1] For instance, the Ordnance Survey Name Books entry asserts that it was “dedicated to St. Mary between 1200 & 1203”. (OS1/2/37/11)

[2] Martin Martin, A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland, in A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland ca 1695 (1703), p. 257.

[3] Matthew Hammond, ‘Royal and aristocratic attitudes to saints and the Virgin Mary in twelfth- and thirteenth-century Scotland’, in S. Boardman and E. Williamson (eds), The Cult of Saints and the Virgin Mary in Medieval Scotland (Woodbridge, 2010), 61-85.

[4] Dennis Meehan (ed.) Adamnan’s De locis sanctis (Dublin, 1958), 118-19.

[5] T. O. Clancy, T.O. and Gilbert Márkus, Iona: The Earliest Poetry of a Celtic Monastery (Edinburgh, 1995), 177-92; Gilbert Márkus, Adomnán’s ‘Law of the Innocents’: Cáin Adomnáin. A seventh-century law for the protection of non-combatants (Glasgow, 1997; Kilmartin, 2008)

[6] Jane Hawkes, ‘Columban Virgins: Iconic images of the Virgin and Child in Insular Sculpture’ in C. Bourke (ed.) Studies in the Cult of St Columba (Dublin, 1997), 107-35, online here. See also discussion in T. O. Clancy, ‘“Celtic” or “Catholic”: Writing the history of Scottish Christianity, AD 664–1093’, Records of the Scottish Church History Society 32 (2002), 5-40, online here.

[7] T. O. Clancy and Sofia Evemalm-Graham, Eòlas nan Naomh: Early Christianity in Uist (2019), s.n. ‘Kilmuir’: https://uistsaints.co.uk/north-uist/kilmuir/ and see further s.n. Saints: “Moire”, from which some of the above blog was adapted: https://uistsaints.co.uk/saints/moire/

[8] Clancy Márkus, Iona, 177-92.