How to arrange your corpses: Saint Odrán and the replication of Iona’s Landscape

Gilbert Márkus

In the twelfth-century Irish ‘Life of Colum Cille’ (a.k.a. Columba), there is a very strange passage in which a saint called Odrán makes an appearance. After travelling all around Ireland founding churches, Colum Cille finally decides to turn his steps to Britain. (It’s worth pointing out that this is completely unhistorical, and it’s fairly unlikely that Columba had founded any churches in Ireland before coming to Iona. People invent stories for their own purposes, but here is not the place to go into that question). So, the story of Odrán in the Irish Life:

“Then [Colum Cille] set out in good spirits and reached the place called today Iona of Colum Cille. It was the night of Whitsun when he arrived …. Then Colum Cille said to his company: ‘It would benefit us if our roots were put down into the ground here’, and he said to them: ‘Someone among you should go down into the soil of the island to consecrate it.’ The obedient Odrán rose up and said: ‘If I be taken, I am prepared for it’, said he. ‘Odrán,’ said Colum Cille, ‘you will be rewarded for it. No one will be granted his request at my own grave, unless he first seek it of you.’ Then Odrán went to heaven.”[1]

This story about Columba and Odrán (later Gaelic Odhran, and often Anglicised as Oran) was further developed in later folk tradition, but this is its earliest occurrence and it is the version that I want to explore here. The story seems to be – at least in part – an explanation of the pilgrimage landscape of Iona and the ritual processes which were taking place in the twelfth century.

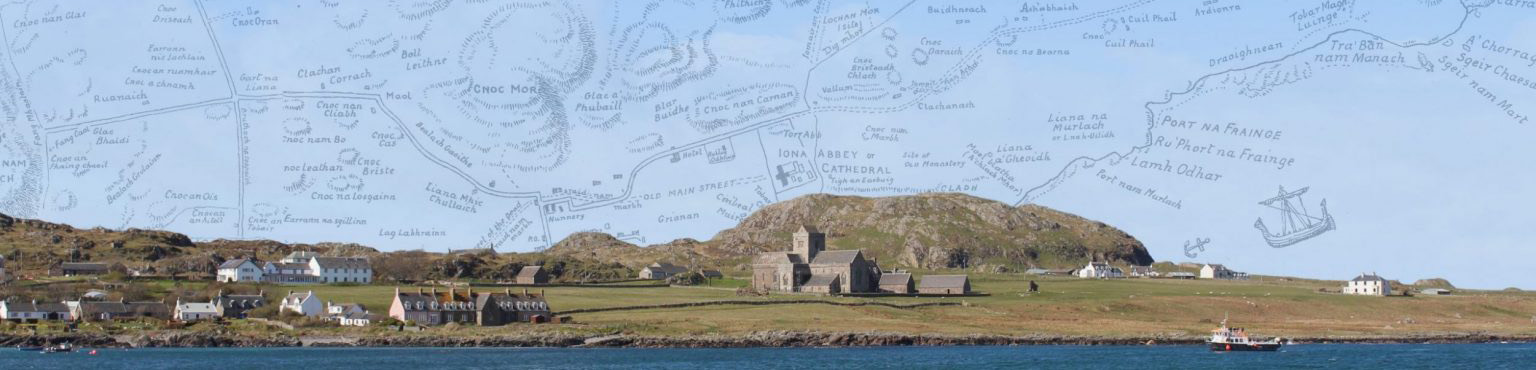

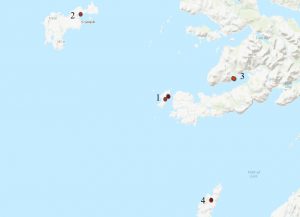

‘No one will be granted his request at my own grave, unless he first seek it of you,’ Columba tells Odrán. Visiting the gaves of the holy dead was a central feature of medieval devotion, and what this story explains is the sequence of graves that the pilgrim to Iona will visit. Arriving at the harbour, the pilgrim will walk north towards the abbey, stopping first at Odrán’s presumed grave, now called Reilig Orain, and then proceeding to the shrine chapel where Columba’s bones lie.

The story can be read as an explanation of the pilgrim experience on the ground. So a story about a personal relationship between two saints is used to explain the spatial relationship between their two graves.

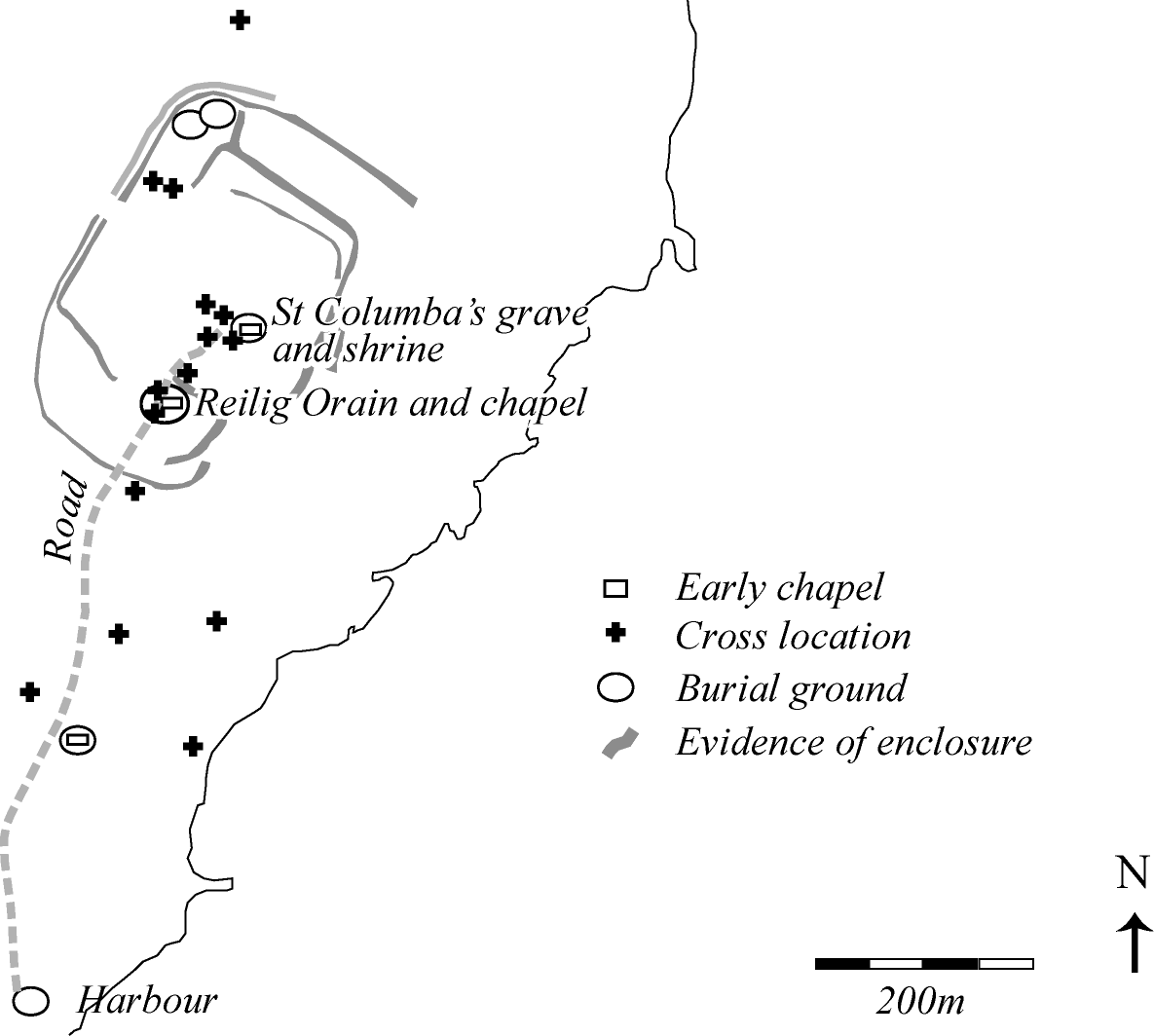

What is interesting is how dedications to St Odrán seems to replicate this spatial relationship in other church sites. On the island of Innishmurray for example, on the Atlantic coast of Ireland, there was a well developed medieval pilgrimage process. Pilgrims landing on the shore proceeded to the main shrine of St Molaise (Templemolaise, within the cashel) by passing through either Templenaman (‘the women’s church) or Relickoran (reilig Odhrain) ‘St Odhran’s cemetery’, in much the same way as those visiting St Columba on Iona passed Reilig Orain there. We might even wonder if Relickoran on Inishmurray was intentionally created as a replica of Reilig Orain on Iona.

Inishmurray monastic cashel and environs

derived by the author from the 1837 Ordnance Survey map

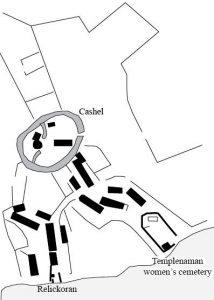

Another potentially useful approach to understanding the cult of Odrán is to look at the distribution of place-names which refer to him by name: hagiotoponyms. There are several in Scotland. Usually a good starting point for this kind of work is to perform a search on the Saints in Scottish Place-Names database.[2] An initial search under the name ‘Odrán’ produces a map with some certain dedications, and some doubtful. Some of the doubtful ones are where people seem to have misunderstood the island-name Oronsay (there are several islands of this name) as a reference to St Oran. However, this island-name is in fact derived from Old Norse Norse örfirisey ‘a tidal island’ – an island connected to the mainland at low tide. Another doubtful one is Tom Orain in Dull parish, Perthshire (NN864368), which seems to have no religious associations and may simply be ‘song hillock’ (tom òrain). Orsay on Islay is shown on one modern OS map as having a chapel of St Oran (NR164516), but again this seems to be the result of a modern misreading of the island-name. The island is recorded in 1507 as Insula Sancti Columbae de Ilanorsa (Exchequer Rolls xii, 589), making clear that the dedication is to Columba, not Odhran.

That leaves us with a clutch of names which we can say with some confidence actually are Odhran dedications as shown on this map, on or close to the island of Iona.

1] the Odhran-names on Iona itself: the chapel and burial ground, Reilig Orain, as discussed above, together with a nearby well (Tobar Orain) whose location is now uncertain and a modern house called Cnoc Orain on OS maps. We have already discussed the spatial organisation of Reilig Orain in relation to the road to Columba’s shrine.

2] Tiree has a cemetery called Cladh Odhrain (NM043472) on the path from the shore to the parish kirk of Kirkapol. The kirk was dedicated to St Columba. This spatial relationship echoes what we have noted about the one on Iona.

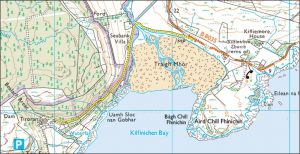

3] On Mull there is a settlement called Tiroran (‘land of Odhran, NM479279), near the shore, and less than a mile from the medieval parish kirk of Kilfinichen, to which it is connected by a road running just above the shoreline. Nearby are Eas Orain (‘waterfall’) and Allt Orain (‘burn’), together with a St Oran’s Well (not shown on OS maps).[3]

4] On Colonsay the former parish church of Kiloran (Cill Odhrain ‘church of [Saint] Odrán’) has disappeared, apparently underneath Colonsay House, in whose grounds is Tobar Orain (‘St Odhran’s Well’). There are some fragments of early medieval sculpture in the garden of the house, and several early medieval burials have been found near the shore, attesting the antiquity of the site, including one ‘Viking Christian’ grave.

To conclude, we have a number of Odhran dedications which form a certain pattern:

- all of them are either on Iona or a short boat-trip from Iona.

- all of them are on islands (three fairly small, one much bigger).

- two of them (Tiree and Colonsay) are intervisible with Iona, while Tiroran on Mull very nearly is.

- all of them are on or close to the shore, and probably close to landing-places on the shore.

- three of the sites (Iona, Tiree and Colonsay) are associated with early medieval churches and burial grounds, and this may be true of Tiroran too in association with the road to the kirkyard of Kilfinichen.

- all of them are associated with or close to churches that once belonged to the abbey of Iona.

Are we looking here at some kind of replication of the pattern on Iona? Was the spatial relationship between Reilig Orain and Columba’s grave somehow seen as authoritatve? Did the story of Columba and the death of Odhran establish a symbolic landscape which could be recreated in different places associated with Iona, thereby recreating some of Iona’s holiness?

The foregoing is a brief summary of one part of a more substantial paper in which I will consider the cult of Odhran at more length and in much greater detail: ‘Church-foundation, the holy dead and the doubling of saints: the cult of Odrán in the early medieval Gaelic church’.

[1] Máire Herbert, Iona, Kells and Derry (Oxford 1998), 261, §§ 51-52.

[2] This online database is free to use at https://saintsplaces.gla.ac.uk/. It is the principal output of a project in the University of Glasgow School of Humanities (Celtic & Gaelic) funded by the Leverhulme Trust and running from 2010 to 2013. The researchers were Prof. Thomas Owen Clancy (PI), Dr Rachel Butter, and Gilbert Márkus.

[3] I am grateful to Christine Leach (Pennyghael in the Past Historical Archive) for information about the well, once treated as a healing well.